Long awaited by theatre aficionados in the city, a rousing new physical theatre production by the Pondicherry-based Adishakti group will finally be staged in Mumbai this week, as part of the ongoing Tata Literature Live festival. Written and directed by the enterprising Nimmy Raphael, Bali opened in April this year, just a couple of days after the birth anniversary of Adishakti founder and guiding light Veenapani Chawla. This is the troupe’s first independent work since Chawla’s passing in 2014.

Epic tales

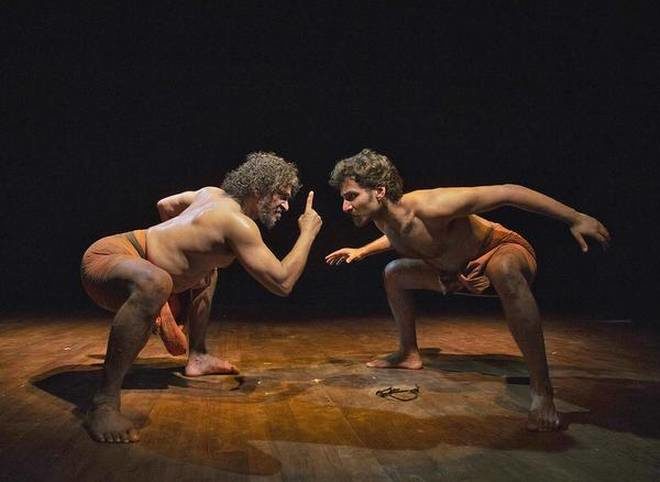

The play draws upon events in the Ramayana leading up to the battle between brothers Sugriva and Bali, the monkey-king of Kishkindha. It is an encounter marked with resentment, pluckiness, and subterfuge, and Rama’s cloak-and-dagger complicity in Bali’s death raises questions about moral ambiguity, irrevocably blurring the line between the heroic and the iniquitous. Straddling the middle ground, Raphael’s production doesn’t apportion blame to one side or the other, instead reveling in the eternal gray of human frailties.

“I have always been intrigued by my own notions of right and wrong, and grappled with how we consider our own positions as absolute,” says Raphael.

The play offered an opportunity to explore different perspectives, even while taking off from an age-old myth with its own narrative obligations.

Bali is not necessarily a fresh interpretation of itihāsa (epic poems/history), but a contemporary piece with topical resonances, particularly in a socio-political climate that has become increasingly polarized, and where conceding one’s ideological ground is now anathema.

As Raphael explains, “It is something we cannot escape at this moment. It is all around us.”

Mirroring life

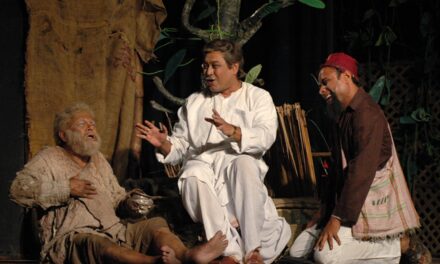

Over three years from 2009, Adishakti had organized a Ramayana festival at its auspices, devoted to performative and visual representations of the great epic. Featuring traditional folk and classical forms as well as urban productions, the festival excavated a range of rich expressions—from 27 Assamese monks performing Sankaradeva’s Rama Vijaya in the rarely seen Sattriya style, to Kapila Nagavallikkunnel’s contemporary interpretation of Sita in the intricately stylized idiom of Nangiar Koothu (an offshoot of Kutiyattam).

“The Ramayana is a mirror of our daily lives, our quotidian experiences find a mirror in its themes,” states Raphael.

It was the personal dilemmas embedded in the tale of Bali that first drew Raphael to it, rather than just the myth. While she had already begun noting down snippets of inspiration, she chose to first create narratives around the personas of Kumbakarna and Laxmana in Nidravathwam, the piece she created in 2011.

Unburdened by legacy

In early 2017, goaded on by frequent collaborator Vinay Kumar, Raphael finally collated her images and ideas, inferences and conclusions, into a dramatic structure which started rehearsals in April last year. The influence of her mentors, Chawla and Kumar, notwithstanding, Raphael’s works are imprinted with her own style unburdened by the demands of legacy. She claims that her plays are not as “intellectual or philosophical” as Chawla’s signature pieces, but they are certainly thoughtful and conscientious in their own right.

A marked physicality of presentation rooted in Indian traditions remains a distinctive hallmark of Adishakti plays, but the journey to the gestural is not negotiated merely by the unleashing of the techniques the troupe has perfected, but by letting the emotions of the characters guide the process.

“It is always a struggle to find moments that are authentic for the characters and the situations,” explains Raphael.

The experimentation continues—for the wrestling duel between Bali and Sugriva, a kushti trainer from Pune was specifically hired to help create a new physical grammar for the production.

Adishakti’s amorphous working style in a rural residency often requires an extended investment of time and disposition that urban actors might be hard-pressed to easily pledge, but Bali appears to have struck a miraculous balance, and its team comprises both of those with a longstanding commitment to the space—Kumar plays the titular character—as well as those contracted for shorter sporadic stints with the production.

This article originally appeared in The Hindu on November 15, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vikram Phukan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.