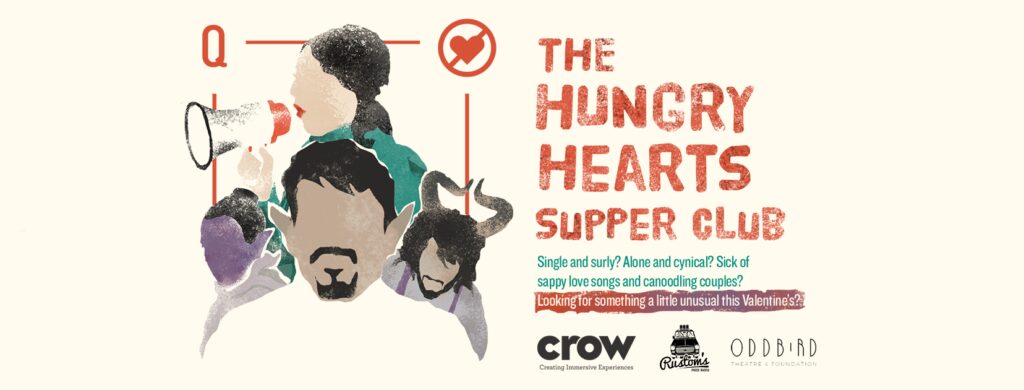

Earlier this year, as a whimsical Valentine’s Week Special targeted the blissfully single rather than the cheerlessly coupled, the Delhi-based Crow, one of the country’s rare immersive theatre outfits, presented The Hungry Hearts Supper Club at Oddbird Theatre. It was a gastronomical experience that allowed diners to dive into a smoky forbidding world of mythical deviants and an outré cuisine replete with a sultry hostess (the Siren) and an Impish (quite literally) maître d’ who served up copious quantities of the “Cream of Nightmare” soup. The storytelling was typically interactive in nature, which could lead to quite unexpected turns of affairs—each diner likely experienced a different show, and was as much a character as a spectator. This is a genre that draws out the more suggestible of theatergoers, but others can also derive the usual vicarious pleasures at just about arms’ length, and between mouthfuls of food.

Earlier this year, as a whimsical Valentine’s Week Special targeted the blissfully single rather than the cheerlessly coupled, the Delhi-based Crow, one of the country’s rare immersive theatre outfits, presented The Hungry Hearts Supper Club at Oddbird Theatre. It was a gastronomical experience that allowed diners to dive into a smoky forbidding world of mythical deviants and an outré cuisine replete with a sultry hostess (the Siren) and an Impish (quite literally) maître d’ who served up copious quantities of the “Cream of Nightmare” soup. The storytelling was typically interactive in nature, which could lead to quite unexpected turns of affairs—each diner likely experienced a different show, and was as much a character as a spectator. This is a genre that draws out the more suggestible of theatergoers, but others can also derive the usual vicarious pleasures at just about arms’ length, and between mouthfuls of food.

Sensorial Pleasures

It must be said that the exotic (at least in terms of nomenclature) nutriments on offer by Crow certainly weren’t as illusory as the setting, with the menu being the brainchild of real-life chefs Rahul Dua and Kainaz Contractor. In many ways, a restaurant outing, already suffused with aromas and cravings, lends itself to the dramaturgical quite organically. Nothing is as persuasive or as stimulating as the appetite, and the truly hungry can be easily cajoled into playing along with a creative romp of sheer imagination mixed in inventively with the evening’s dining spread in striking ways—satisfying the stomach as well as the soul (if we’re lucky). This is far beyond what is usually conjured up by supper theatre outings where your plate, filled to the brim with hors-d’oeuvres, is at a distinct remove from the shenanigans on stage, the intermingling of sensory flavors never quite achieved.

Exploring this piquant relationship between food and theatre is Dishoom, an Indian casual dining chain in the UK. Its first outlet opened in 2010 at Covent Garden, bang in the middle of London’s theatre district at the West End. Its latest Irani-style café formally opens on December 15 at upscale Kensington. To mark a soft launch, Dishoom’s proprietors have commissioned Swamp Studios–a theatre company specializing in experiential site-specific work—to create Night At The Bombay Roxy, an immersive theatre production “with live jazz, drinks, and dinner” directed by Eduard Lewis that takes place at the premises of the spanking new restaurant itself. Starting this week, the play runs for an entire fortnight, before the site’s official opening. The eatery’s vintage jazz-bar feel and Art Deco interiors, with period furniture, artwork and light fittings sourced from India, certainly evoke quite instantly the 1940s Indian noir settings of the play.

All That Jazz

The production is inspired by Naresh Fernandes’ Taj Mahal Foxtrot, the well-regarded tome on India’s jazz history that has influenced a glut of work in film and theatre. Anurag Kashyap’s atmospheric Bombay Velvet and Bardroy Barretto’s Konkani musical drama Nachom-ia Kumpasar, both draw substantially from the tempestuous life of Goan crooner Lorna Cordeiro, on whom Fernandes has penned an in-depth essay. His research has also spawned Ramu Ramanathan’s Jazz, about Goan musicians who brought the genre into Hindi film music between the 1950s and 1970s; this writer’s Bengalee Baboo, a short play on blackface minstrel Dave Carson that featured in Sunil Shanbag’s Stories In A Song; and now, Night At The Bombay Roxy. The Bombay Roxy is a café and jazz club from 1949 that could well be Dishoom’s fictional alter-ego, and its well-accoutered actors will seek to transport guests to Bombay’s thriving mid-century society scene, “where the jazz is hot, and the atmosphere is heady.”

In the play, Sophie Khan Levy plays Ursula Vaz, a Cordeiro-style songbird with her own backup band, the Marine Liners, and Vikash Bhai is club-owner Cyrus Irani, who is seeking to turn around the fortunes of his establishment, once notorious as a hub for racketeers. The cast comprises primarily of British Asian talent, with the exception of Manish Gandhi, an Indian actor who has received encouraging reviews earlier this year for his turn in Glenn Waldron’s teenage drama Natives, which also marked the stage debut of Dunkirk’s Fionn Whitehead.

London Calling

Conceptualised by frequent collaborators Ollie Jones and Clem Garritty, Night At The Bombay Roxy is just another stop in London’s frenetic immersive theatre scene, with many running productions centered around the dining experience—in Binaural Dinner Date, headphones guide you through an encounter with a stranger, while Beauty And The Feast is “set in a grand old French château on the night of a grand feast.” Then there is the tour of a derelict Victorian house in Till We Meet Again where audiences attempt to discover the dark portents of Elizabeth Inchbald’s 1792 tragedy The Massacre, while a revival of The Great Gatsby urges guests to hit the dance floor in retro chic. The disarming interactiveness certainly raises the adrenaline of those spectating, but in the end, the proof of the pudding is solid foolproof writing and pugnacious actors who can think well on their feet.

Dishoom’s Bollywood-inflected showcase highlights the fascination that mainstream Indian cinema holds for British audiences with a taste for the subcontinental. Their chicken tikka masala must come necessarily laced with a dash of oye shava or balle balle, as well as the Indian diaspora who, in the relative absence of access to rooted Indian traditions, have appropriated an easily exported massy idiom as their own. It is a cultural capital that has been amassed in accelerated fashion over the past two decades—which has seen several Indian films crossing over and making an impact at the British box office. In UK theatre circles, looking at Indian-themed productions over recent years, Bollywood and its tropes have never been anathema in the manner it is in the Indian experimental stage, whose proponents are always looking to negate the influence of a commercialized industry that promises a lot of glitz but never as much depth.

Yet it must be said that it is always possible to marry style with sensibility, and perhaps very much so in the immersive setting of a London eatery with more than just Bombay nostalgia on the menu.

This post originally appeared on The Hindu on November 28, 2017, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vikram Phukan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.