In the theatre, the front curtain is drawn open from both sides of the proscenium to reveal a stage set, while the classic raising and lowering of the curtain establishes the temporal boundaries of drama and indicates the finale or the opening of the play.

The theatrical curtain, also, divides the world of “reality” from the world of representation, and the realm of every day being from the realm of performing, but, can it separate the realm of “truth” from the realm of “falsehood”?

The exhibition “Avlaia (Drop Curtain),” which was held in the Markideio Theatre, opened the Curtain of the south-east borderlines of Europe, in Paphos, Cyprus during the finnisage of the European Capital of Culture Pafos 2017. It was an attempt to formulate questions about the future of Europe that might allude to their solutions, since, as Karl Marx notes in his work On the Jewish Question, the ‘formulation of a question is its solution.’

The Dispute and A Solution

The participating visual artists, from the region of the Mediterranean, propose symbolic solutions to the times of European crisis, when faith has been exhausted and old utopias have failed, while the exhibition consists of poetic reflections about the long-suffered question of the landscape of divisions in Europe. In addition, “Avlaia (Drop Curtain)” discloses discourses that are actually able to open up new and varied alliances that transgress the national, ethnic and religious conventions that dominate our political and geographical realities.

The Cyprus dispute or “issue,” namely, the ongoing issue of military invasion and continuing Turkish occupation (since 1974) of the northern third of the island, marks one of the most vexed division cases in Europe. The European Cultural Capital was designed to highlight the richness and diversity of cultures in Europe, celebrate shared cultural features, increase European citizens’ sense of belonging to a common cultural area and foster the contribution of culture to the development of cities. Therefore, these original principles of the European Capital become decisive for the creation of signification and acquire their meaning in the cultural milieu of a city such as the ancient port of Paphos in the divided Republic of Cyprus.

The international complications of the ethnic dispute between the Turkish and the Greek islanders stretch far beyond the boundaries of the island of Cyprus. We cannot correct the pages of a history which never quite took the course we wanted it to, but artists can speak out about the devastating things that have happened and aim to resolve conflicts and failures, based on notions of solidarity, communality, mutuality, but also on the ways that art can raise awareness with regards to the involvement of civil actors and civil society organizations.

The Curtain opens to illuminate the complex past, the world of migration, the political and geographical displacements and the disintegration of reality as we know it. It also discloses our common and constantly rewritten history. Avlaia is a fantasy put on the stage of History!

Futures of Europe

The history of Europe is associated with democracy and it is common knowledge that currently, democratic values are under threat. The necessity to re-invent and protect democracy lies on a focal premise that emerges from our recognition of the dimensions of the European “crisis.” It is impossible to proceed without scrutiny and since the word crisis derives from the Greek verb “κρίνω”, to judge, it would be helpful to see the potential of the word in the context of a transgressive and transformative κρίνειν — namely transgressive judgment. As Stathis Gourgouris argues, ‘the tradition of transcendental thinking has never offered humanity anything better than the blissful pill of oblivion, while a transgressive, transformative thinking takes one’s individual finitude as the point of departure and draws from it the energy to combat whatever forces might risk humanity’s irreversible end.’ (Gourgouris, S. (2010) “We Are An Image of the Future. The Greek Revolt of December 2008” (review), Journal of Modern Greek Studies, 28(2) 366-371.)

European crisis can be seen as the intensification of a pre-existent process or illness that has reached a critical point that can resolve itself in death or that can be cured before reaching the final point. Cultural production can be the vanguard of this counter-attack to crisis providing that it can release political and social forces that could eventually realize Europe’s potential. The transformative potential of art lies in its resistance to aestheticize (and thus depoliticize) the significance of the current political conditions and events. The sense of community – of dialogue in a common “language” – and a performative communal engagement is at the heart of this endeavor.

The counter-hegemonic practices of radical art stimulate resistance to those who are already inclined to alternative ideologies and practices, however, it is collaborative/collective nature and public reiteration can also affect and influence people who are not part of the movement, to begin with. It becomes evident that the aim of political art is not to preach to the converted but to influence a wide spectrum of society.

The Theatrical Curtain

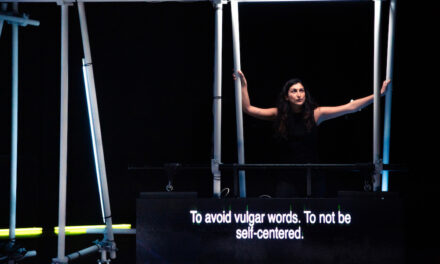

The participating artists stage their works using the conventions of the theatre and artists present a “mise en scene” that opens the curtain and reveals our political and embodied histories as well as our inhabited fictions. Τheatrical representation is employed here to suggest, allude and propose solutions of how visual representation and the virtual can enable the real.

Theatricality can no longer be understood as a reflection upon theatre that is the domain of artistic activity or as an extended metaphor of human life, but rather as a ‘means of inducing the audience to watch themselves as subjects that perceive, acquire knowledge and partly create the objects of their cognition’. (Sugiera, Malgorzata. ‘Theatricality and Cognitive Science: The Audience’s Perception and Reception’, SubStance, 31.2/3, special issue 98/99 (2002): 225.)

Theatricality is the philosophical discourse of performance and is considered as the conceptual machinery of representation. In theatre theory and historiography the term is applied in diverse ways, yet studies in philosophy, anthropology, ethnology and sociology, political, historical and communication sciences, cultural semiotics, history of art and literature have identified and applied the concept of theatricality as a cultural model beyond a purely metaphorical use of the term, and they have also employed the concept of the theatre as a heuristic model to a wide extent. According to Timothy Murray, Foucault conceived the notion of ‘Theatrum Philosophicum’; Lyotard analyses the ‘political stage’; Baudrillard studies the ‘stage of the body’; Clifford Geertz explores the ‘theatre state of Bali’; Paul Zumthor proclaims the performance of narrators in oral cultures to be ‘theatre’; Ferdinard Mount investigates the ‘theatre of politics’; Hayden White explains ‘historical realism as tragedy’; and Richard van Dulmen analyses the history of tribunal practice and penal ritual as a ‘theatre of terror culture’.(Murray, Timothy (ed.). Mimesis, Masochism, and Mime: The Politics of Theatricality in Contemporary French Thought. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997: 218–20.)

The existence of philosophical anti-theatricalism is a symptom of the conflictual entanglement that binds the theatre and theory together. Theatre and theory are engaged, as Puchner remarks: ‘in a struggle over visibility, material mimesis, and the presence and liveness of the theatre, notions that theory wants to wrest from the theatre in order to revise and integrate them into its own apparatus. The theory thus creates its own concepts of theatricality, which are prone to be at odds with the real theatre. The struggle between theory and the theatre is fought through a variety of genres and art forms, including the closet drama and the manifestos of the avant-garde’s conceptual theatre.’[Puchner, Martin, Against Theatre: Creative Destructions on the Modernist Stage (edited collection with Alann Ackerman), New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. In http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/~puchner/theaterinmodernistthought.pdf]

Contemporary art and theatre reciprocally pose interesting challenges to the legacy of theatricality through interdisciplinary artistic activity, working with diverse artistic disciplines, connecting and integrating the aural and visual media by way of developing new media forms (combinations of film, video, computers, etc.), application of various technologies, spatial installations, and finding new ways of presenting art.

Nevertheless, theatre becomes a large medial framework, that incorporates different media without negotiating the assumed live quality of the theatrical body. The visual and theatrical practice is often seen as constituting and constructing each other, operating as an axis that allows media relationships to be established. It is significant to note that theatre is able not only to represent but also to stage other media.

By employing the metaphor of the Theatre in its curatorial approach, the exhibition used theatre’s medium specificity so as to stage a field that contains within its phenomena a heterogeneous collection of interdependent media. Media in the case of “Avlaia” become visible as media, as means of communication, each with its own materialities, medialities, and conventions of perception.

Moreover, the curator and artists drew from the notion that the theatre fails to exist in perpetuity like an object, so as to highlight the precarious political realities that are experienced in the Republic of Cyprus. Unlike a visual art piece, the theatrical performance was disappearing as it was being experienced. Peggy Phelan emphasizes the contingent aspects of performance by considering that its most irretrievable failure of all is its ‘total disappearance and non-existence.’ Phelan also celebrates the staging of disappearance in performance as ‘representation without reproduction.’ Embedded in this notion are the singularity of live performance, its immediacy, and its non-repeatability.

Consequently, the dropping and opening of the theatrical curtain aimed to elucidate further, the multifaceted notions of artistic practice, but also the importance of art in generating counter-hegemonic politics, transformations, and solutions, as well as the ways cultural production can affect the future of Europe, the Mediterranean and Cyprus, since as Franco Berardi claimed, ‘when political thought, practice, and imagination loses hold on “the future,” it goes into crisis.’

_____________________________________________________________________________

The exhibition “Αυλαία”, was held in the Markideio Theatre, refers to the ending – or the beginning – after a year full of events, connected with thoughts, ideas, and feelings about the European Capital of Culture Pafos2017. The exhibition is linked to the Official Handover Ceremony of the European Capital of Culture Pafos 2017, when Pafos passes on the baton to the next European Capitals of Culture and showcases through sculptural installations the space and the meaning of the theatre.

With the participation of the following visual artists: Theodoulos Gregoriou, Angelos Makrides, Nikos Kouroushis, Yiannos Economou, Andreas Savva and Gioula Hadjigeorgiou from Cyprus, Danae Stratou, Kostas Varotsos, Peggy Kliafa, Yiasemi Rapti and Vally Nomidou from Greece, Vince Briffa from Malta.

Organization/Curation: Gioula Hadjigeorgiou

With the collaboration of the European Capitals of Culture Valletta 2018, Elefsis 2021

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Sozita Goudouna.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.