Alexei Nesterov, an actor in my wife Oksana Mysina’s film, Insulted. Belarus(sia), sent her a thank-you email after the film’s premiere. “I am so grateful you reached out to me,” he wrote. “Participating in this film validates my entire career as an actor.”

I have lived with Alexei’s words ringing in my head for much of the last year. It feels as though they have become my own.

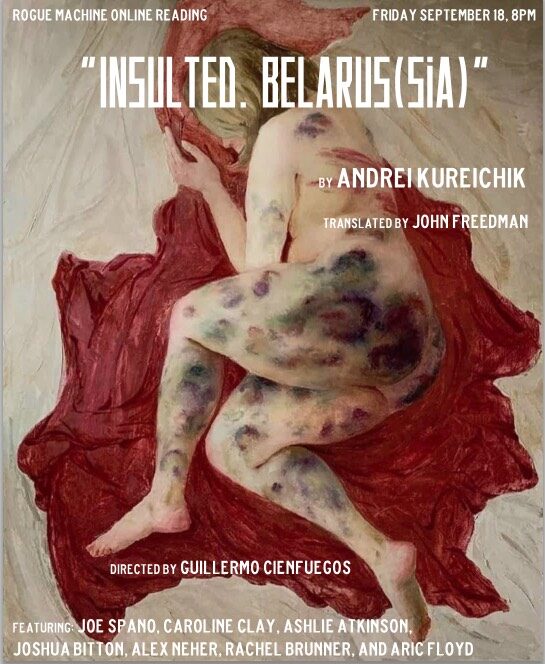

I had no idea—let me repeat that with emphasis—I had no idea what the future held for me when I received a message from Andrei Kureichik on September 9, 2020, at 3:13 p.m. He informed me quite nonchalantly that he had written a play, and he wondered whether I might translate and publish it, or maybe get someone to read it.

Less than eight hours later I wrote to say that five theatres in two countries were on board, and more would join soon.

I was still, at that moment, utterly ignorant of what was about to go down. From my current vantage point, however, I can confirm: the Worldwide Readings Project of Andrei Kureichik’s Insulted. Belarus was already well underway.

The details of “who, what, where and when” are available in numerous sources, the most important of which are referenced in a Wikipedia article about the project. But let me offer some bottom-line numbers here as a general outline of the first year of this play’s life. In roughly twelve months, the project saw:

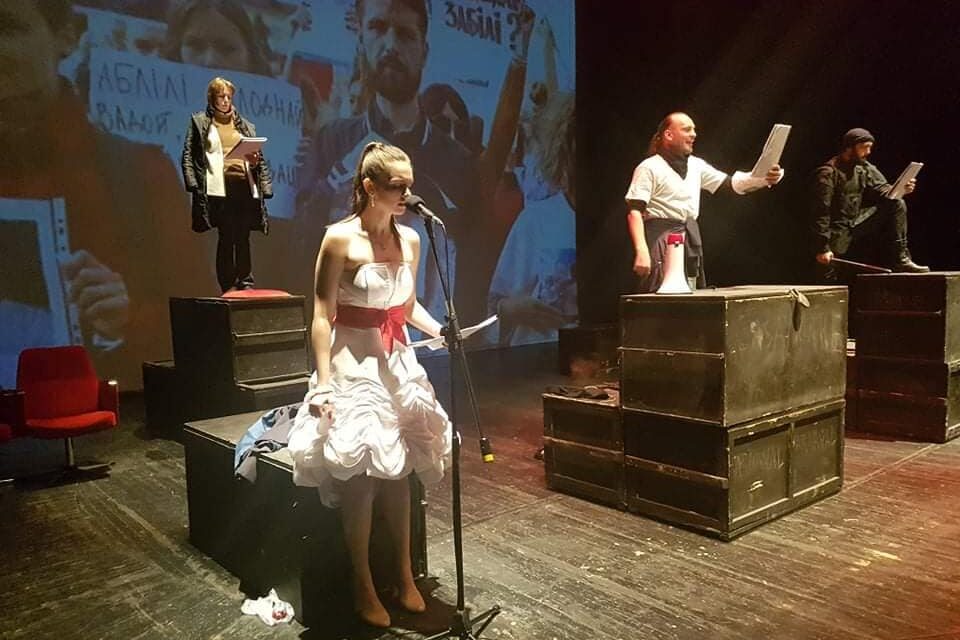

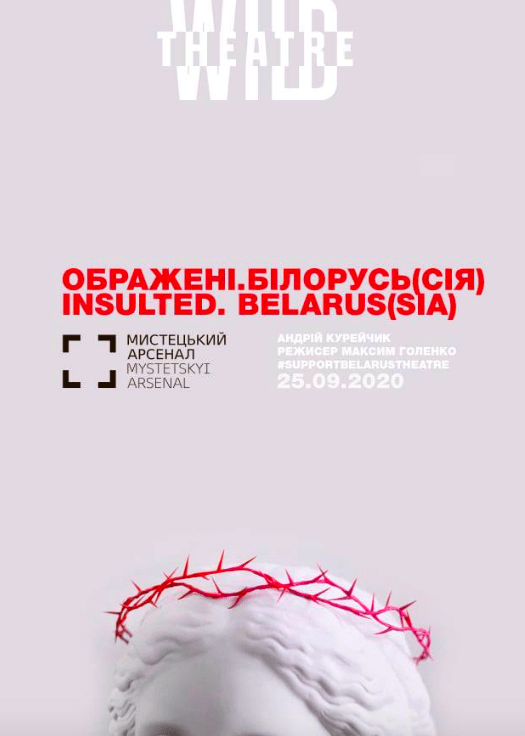

- 130 readings or productions in 32 countries and 102 venues

- 212 total events (this includes readings + seminars, conferences, webinars, videos, installations, translations, publications, etc.)

- 25 translations into 22 languages

These numbers may mean one thing to one person, something else to another. For me, they bring back an echo of Alexei Nesterov’s words: “My participation in this validates my entire career.”

In thirty-five years as a scholar, historian, translator, writer, and critic, I never asked theatre to bring me politics or reflect my political point of view. I wanted more than that. I wanted theatre to have deep meaning. It had to reach into my gut to get my attention, to say nothing of my approval. Lacking any connection to or belief in a religious approach to the world, perhaps I saw theatre as a place where I could worship at the altar of life’s experiences. But it was not a place where I looked to see political battles. More precisely, perhaps, over the decades, I invariably found that theatre that brought me politics was weaker, less convincing, and less believable than theatre that struggled with human paradoxes on a higher, more philosophical, or purely artistic plane.

We can argue these things; I’m not claiming access to any kind of high truth. I am merely setting out my own lifelong attitude that was shaken, broken, and made whole again by Andrei Kureichik’s Insulted. Belarus. Let’s remember what was in the air as I downloaded this new play from Andrei’s message.

COVID-19 was running rampant, scaring half of the vaccine-less world, angering the other half. The Donald Trump Train was on a crusade to unmake American democracy. Police forces in America were attacking citizens declaring that Black Lives Matter, while coddling up to white supremacists. Boris Johnson was shoving Brexit down everyone’s throat in the UK (and Europe). Vladimir Putin was becoming increasingly unhinged in his official behavior, his most recent atrocity coming just nineteen days before that email arrived, the attempted murder of opposition leader Alexei Navalny by poisoning.

For an American who, like myself, had lived in Russia from 1988 to 2018, it was getting to be too much to bear. I increasingly felt like I had wasted my life entirely. The country I was born into and the country I had adopted were both tanking. Nothing I had “accomplished” in my professional life was worth a bent nickel under these circumstances. “My little world of art” now seemed idiotic as the world went fascist. My colleagues in Russia were hiding their heads in the sand, some weirding out and snapping, others carrying on with glassy faces that suggested, “I’m not here, I have nothing to do with this.” American colleagues were determined, but in despair.

And now, amid all this, Belarus, the former Belorussia, known way back when as White Russia, a land that almost never made it onto anyone’s radar, whether it be historically, politically, or culturally, seemingly suddenly, and quite unexpectedly, took a giant step into the international spotlight.

Who expected the self-proclaimed “housewife” Svetlana Tikhanovskaya to take over her husband’s presidential campaign when Lukashenko threw him in prison? Who expected her to join forces with three other women who were attached to presidential candidates either under arrest or under threat of arrest? Who in God’s name expected Tikhanovskaya to win the election on August 9, 2020, with an estimated two-thirds of the vote? And when Lukashenko just did what dictators do—began crushing the rebellious populace with storm troopers—who could have possibly expected an entire nation of young people, old people, white collar professionals, and factory workers to rise and rebel?

It was one of the most astonishing, hope-inspiring events in recent memory.

When Andrei Kureichik sent me his play, he didn’t realize it, but he was asking me to step up and take part in history. He was providing me a tool, and the encouragement, to stand against wrong and evil. His play was a rare beast—a brilliant piece of finely crafted dramatic literature that threw itself heart and soul into the political moment. By taking on this play, I felt I was rising personally to oppose the dictator Lukashenko. And, by opposing Lukashenko, I could feel myself actively opposing Vladimir Putin, Donald Trump, Boris Johnson, Jair Bolsonaro, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and everyone else of their ilk.

It was a worthwhile endeavor. I leapt in headfirst.

As my contacts around the world grew—sometimes because I found them, sometimes because they found me—I was amazed and gratified to hear a similar phrase repeated by many, “Kureichik’s incredible play strikes a nerve. If I were to change a few names and places, it would be a play about where I live.” I heard this from colleagues in Hong Kong, Nigeria, the UK, all over the United States, Chile, Mexico, and more. Directors and actors in many of these countries wrote that this play gave them an opportunity to speak out and protest injustice around them in a way that they hadn’t been able to up to now.

The year of 2020 was one in which people of the world were getting fed up with being insulted by their governments, politicians, their neighbors, and their relatives. And since all of us were essentially trapped at home, locked down in defense against a pandemic killing us by the millions, we were ready to explode, ready to take action in whatever limited ways we could. Zoom, Skype, Facebook Live, YouTube Live, and other social media hosts gave anyone who wanted it the opportunity to gather with friends while maintaining proper social distancing and to let off steam, to have their say about the world going wrong.

There you have the Worldwide Readings Project of Andrei Kureichik’s Insulted. Belarus in a nutshell. Through it, through all of the artists, theatres, schools, and even amateur groups that joined us to tell the story of the Belarusian people battling the insulting behavior of an illegitimate government, all of us began to feel a sense of community, of shared values, shared goals, shared hurt, and shared healing. We all, I feel safe in saying, experienced a sense of shared gratification that we were doing something of importance. We took a stand, we encouraged others to do the same, and that led to others joining in the chain.

I must mention the single significant disappointment that this project brought me. Despite the enormous parallels that Insulted. Belarus shares with the current situation in Russia, not a single former Russian colleague has ever once so much as acknowledged to me over this last year the existence of Kureichik’s play. While I was fielding thousands of letters from all over the world, sharing detailed discussions about the nuances of Kureichik’s play and the possibilities of future collaboration, not a single Russian colleague contacted me, commented on the readings, or showed interest in the project. Not one. Zero.

In his original letter asking me whether I might arrange a reading or two in the West, Kureichik had written, “I have few hopes for Russia.” As if he had looked into a crystal ball.

A friend in Poland wrote to me and asked, “Has anyone in Russia ever said anything about Insulted. Belarus? I wrote to [and here he named four or five prominent mutual Russian colleagues], but no one ever answered me. What do you think is going on?”

Now, my guess is probably better than most as to what is going on, but I will allow this particular story line to hang unresolved. My reason for bringing up the dearth of Russian responses was not so much to point fingers (well, maybe, one or two) as it was to highlight the extreme courage and commitment that Belarusians showed when their dictator backed them against the proverbial wall. It was their sense of responsibility, their need to stand up against might, their instinctive sense of fortitude and fearlessness that made me and so many around the world want to come to their defense. In doing so, we were defending our own worlds against tyranny.

Thank you, Andrei Kureichik! Thank you, Belarusians! Thank you, all of you, who stood up to answer insult with wisdom, bravery, talent, and caring. You changed the course of this writer/translator’s life, giving me a sense of purpose I had not experienced in many a year.

It is a fact that the heady days of the revolution in August 2020 turned to very dark days of depression for Belarusians in 2021. For the moment, Lukashenko has put the lid back on the discontent by employing the brutal, violent tactics of torture and murder. But Belarusians are astonishingly resilient if nothing else. They continue to find ways to protest, to make their hopes and beliefs known to the world. Sometimes all they can do is gather ten people who mask their faces, go into the forest, and unfurl the characteristic white-red-white flag of the revolution for thirty seconds in front of a camera.

Not much, you say? Well, Lukashenko has not beaten them.

Andrei Kureichik, the creator of Insulted. Belarus.

In his continued effort to employ art in the service of fighting evil, Andrei Kureichik delivered a new play in July, Voices of the New Belarus. This strictly verbatim piece offers fifteen actual voices, fifteen actual published texts of Belarusians who had the misfortune to encounter Lukashenko’s vile police state following last year’s revolution.

Now we are bringing this play to the world. In the first three weeks of its life, it was translated into ten languages.

This year Belarusians, and a lot of beautiful, sensitive people around the world, have taught me an invaluable lesson: Have hope, keep busy, don’t give up.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by John Freedman.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.