At the University of Pretoria, South Africa’s Student Gallery, I was met with the open space of the gallery floor with the white walls adorned with the framed photographs of one of South Africa’s most distinguished photo journalists, Peter Magubane, who was arrested by apartheid police several times throughout his career for documenting impactful events that occurred throughout our nation’s history, such as the Sharpeville Massacre of 1960, the Soweto Riots of 1976, and even Nelson Mandela’s release in 1990. The photographic hanging display near the entrance greeted me with fragments of his life story within his biography, as well as the driving force behind his photographic and journalistic work.

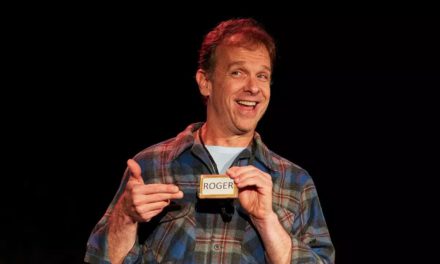

Performer: Human van der Merwe. Photographer: David April (@davidaprilphotography)

The photographs in black and white provided me with glimpses of our country’s painful past, and they appear to me as memories that I can feel, yet struggle to remember for I was not there during those times. Memories of mothers and sisters protesting for the right to let their voices be heard, images of youths confronting the harsh brutality of the police, the collective grief over the loss of loved ones who perished in the face of apartheid. Yet, I’m also fascinated by the moments of joy captured in that same monochrome palette, with smiling beachgoers, comrades shaking hands on the street, and the captured faces of young children playing, all frozen in time, yet ever so transcendent.

And suddenly, the gallery began to transform with the sound of singing, as “ghosts” of the past, dressed in dull colors of black, grey, and brown, entered the room slowly, yet carrying an almost mystifying air around them. I found myself being slowly transported into a time unfamiliar to me (yet one I almost recognize as part of my own) while simultaneously the past slowly pours into the present. This strange blurring of time and space compelled me to watch the past as it unfolded in front of me and to listen to the voices singing our shared stories.

Performers dressed in colorful clothing immediately drew my attention, each one dressed as representative of the people of the past, with a collection of snippets from apartheid-era South African play texts being stitched into the performance itself. Audience members were given the chance to engage and disengage with the performance as they saw fit by walking around the space or choosing to remain in a single spot focused on a particular performer’s movement or story, almost as if a museum came to life. The accompanied soundscape provided by the ghosts reverberated throughout the space, as I watched the couple, Philemon and Matilda, from Can Themba’s short story The Suit greet each other with the sounds of rain encapsulated within a tube. He raised his voice in frustration as the water poured outside of his invisible yet visible home. I see the physical props and dangling microphones being used to immerse myself into the world, each operated and used by the other performers, and yet it did not feel alienating in the slightest, but rather felt like a reminder of where I was. I was in the gallery hall watching a performance, while also becoming an explorer of the past as I traveled through the liminal space, observing the photographs and the ghosts frozen in place.

The soundscape of the ghosts transformed jolted my heart with waves of pain and moments of blissful reprieve, ranging from the sounds of joyful ululation and cheerful stomps to the painful, scarring sounds of gunshots being fired, provided by the texture of newspapers. A signal, perhaps, of newspaper covers decorated with front-page news of tragic deaths, stories of police brutality, harsh laws of segregation. The voices of White police officers asserting control over the marginalized Black citizens with demands of passbooks and demands of compliance. These all reminded me of the harsh realities faced by the people of my parents and grandparents’ generations, harsh realities that I found myself glad to not have ever experienced.

Now the barrier between past and present grew even murkier as the performers invited us to move to a different space in the hall, transforming us from observers to invited guests. I’ve seen spouses communicate over telephone lines across far distances, yet seeing them so close to each other as if their presence were transported over from the walls they inhabited, with an imprisoned Philemon and a Matilda safe at home, face to face, yet geographically separated from one another.

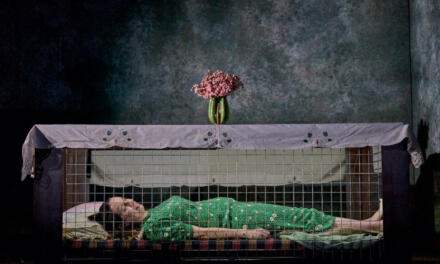

And upon the ending, as Matilda is found dead with the suit in her arms by Philemon, I felt as if he pleaded and yelled at us attending for just standing by and watching history unfold when he addressed the lord in the skies above. And as the ghosts sang their song of Amahemhem which faded into the recesses of my subconsciousness, the doors opened and the audience was invited to leave. Amahemhem, which in isiZulu, refers to the spreading of news and rumors. The cast of performers in their clothing smiled and became frozen in time, locked in a photograph that compelled me to remember, despite the space of the gallery signaling to me that it was time to leave, time to carry and share what I heard and saw with others around me.

Performers: Shamiga Makaku and Priyanka Bandu. Photographer: David April (@davidaprilphotography)

I was left with a heavy heart that left me feeling grateful for the sacrifices that these people, connected to me not by blood but by memory and soil, have made to let me live in a country where such barbaric nightmares and wounds cannot touch me. And yet I felt a sense of longing and sadness, wishing that I could take them with me away from the horrors of the past, as well as mourning a profound spirit of collectiveness that seems to have weakened over the years. I found myself reminding myself to always remember the scars embedded in our country from its violent past as we marched and kept marching forward to build something new. I found myself wishing that the sense of community, the spirit of unity, that spirit of human perseverance, was still as strong today as it was back then.

Amahemhem was more than just a beautiful performance incorporating elements of radio, live soundscapes, and embodied images of the past within a gallery, it was an invitation into the life of South Africa’s yesteryear, a mixture of nostalgia and somberness with a dash of joy to remind us to build a better world for ourselves without never letting go of what came before us. A reminder to carry the past with us such that we never relive or re-experience the wounds of our dark past as we climb towards creating a better life for ourselves and for those who shall come after.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kopano Masibi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.