South African performance artist, writer and cultural worker Kopano Maroga interrogates the intersections of God, magic and art. They discuss their involvement in Alesandra Seutin’s Mimi’s Shebeen, focussing on the magical techniques employed in the process of creating the work. They then reflect upon theurgy, a branch of magic, as it applies to Amanda Piña’s performance piece EXÓTICA. They conclude with reflections on their work as a dramaturge on Carolina Maciel de França’s The Hero’s Journey of Anastácia and the archetype of The Trickster, a mischievous deity who can move between the mortal world and and the immortal.

Four candles for the four directions sit alight around me: one in the east for air, one in the south for fire, one in the west for water, one in the north for earth. Before me, in the centre where I sit, cross-legged and attentive, sits a candle for the direction of the centre: the direction of the self, of Spirit. This is how I have been instructed by my magical mentor and dear friend, Louise Westerhout: herself a seasoned magical practitioner in the traditions of Wicca and the secret magical traditions that have no name but know hers. They have transported themselves from dusty books; from the ether of the cosmos; from those human and more-than-human guides who have mentored and taught her the traditions of Wicca, Reiki, Yoga and therapy; through the invasion of cancer into her body that made way for a delicate divinity to rattle through her bones, and rattles still. I sit, with Louise’s words whispering in the sepulchre of my mind, entreating me into the tradition of making A sacred space. A space for that elusive familiar: magic.

Starhawk, the cofounder of Reclaiming, an activist branch of modern Pagan religion, in her article The Magical Battle of This Time borrows the words of occultist Dion Fortune when she defines magic as such:

Magic — by Dion Fortune’s definition ‘the art of changing consciousness at will’ — in this sense is not waving wands or pulling rabbits out of hats. It’s the heritage of ancient psychologies that admit multiple forms of consciousness — the remnant, in the West, of old indigenous understandings of the world as infused with life, consciousness, presence and underlying patterns.1

How I interpret this definition, inherited from Fortune, of magic being the ‘art of changing consciousness at will’ requires a few qualifying statements2 from me:

- Art: an intentional practice of translating immaterial matter and phenomena (such as ideas, thoughts and feelings) into material matter and phenomena (such as dance, song, casting circles for sacred space, weaving, pottery, poetry, incantations etc).

- Consciousness: our individual and collective ability to perceive both material and immaterial matter and phenomena. What we sense and what we feel, in the broadest definition of the words.

- Will: our individual ability to experience and exert our desires on material and immaterial matter and phenomena.

With these definitions, the quote above from Fortune can be understood to be that magic is the practice of changing the material and immaterial world(s) as and when one desires. My understanding of this definition is informed by a socio-political framework wherein I believe and understand that as individual beings we are woven into a complex fabric of interdependence on our environment. We are products of both ‘nature and nurture’, so to speak. Further, who we are, what we are able to do and what we desire while we are in this particular physical form is in conversation with who other human and more-than-human entities are and what they are able to do and what they desire. For example: our collective identity (who we are) as entities that need and want to eat (what we desire) is made possible (what we do) by the so-called natural world and the natural world’s cultivation by farm workers and food production and dissemination institutions (i.e agriculture and the private and public sector(s)). Thus, what we call ‘magic’ is, in fact, very mundane.

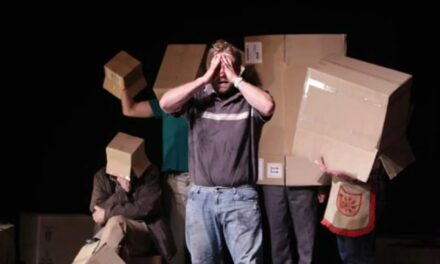

Mimi’s Shebeen by Alesandra Seutin, photo by Danny Willems.

Through our everyday acts of domesticity, play, sociality and reproductive labour (caregiving and domestic housework roles including cleaning, cooking, childcare, and the unpaid domestic labour force3) we are performing magic all the time. However, here is where the ‘art’ comes in. Because much like we almost all use our bodies and voices, hands and minds, all the time, there are those among us who use these faculties as part of an intentional practice towards the cultivation of a craft, i.e. artists. Thus, in the same way that we consider dancers, musicians, actors, illustrators, painters and ceramicists to be artists, the same can be said for those who call themselves witch, healer, oungan, magician, warlock, priestess, curandera, isangoma, manbo, shaman and igqirha. And, further, there are those among us who combine these practices of magic and art to create specific, syncretic practices that weave the two such that they are indistinguishable from one another. Arguably, in these specific practices, the two become one, striking out their own Path in the magic worker’s Way. And, thus, some of the questions for us in Western Europe, where these practices begin to become seemingly more visible in the world of art making and cultural production, are: is this a new ‘trend’ within art making; what traditions are these practices drawing from; what is inspiring these artists to work in these ways; what are the cultural dynamics these practices stimulate, or form a part of?

MAMA AFRICA: PAN-AFRICANIST SANGOMA CHANTEUSE

South African musician, activist, mother and Pan-Africanist Miriam Makeba (affectionately nicknamed Mimi and Mama Africa) is world famous for her music and activism. However, lesser known, is her status as isangoma: a traditional, ancestral healer and diviner in the Nguni and setswana cultures of Southern Africa. It is the figure of Miriam Makeba that Belgian-South African dance, theatre and performance artist Alesandra Seutin takes as the starting point for her work, Mimi’s Shebeen. This is a dance theatre piece that I worked on as a pre-dramaturgical researcher and, eventual, performer in 2022 and 2023, myself coming from South Africa and having lived there from my birth in 1994 until 2019 when I moved to Belgium.

In South Africa we have what are called shebeens: a mix of a bar, club and tavern which have served, historically, as spaces of intense politicisation, sociality, social release and, often, as with any place where alcohol is the main device of social lubrication, violence. Further, historically, we had what were and are known as shebeen queens. The term generally refers to the women proprietors of the shebeens, but sometimes could be used to refer to the queens who activated the shebeens: through their energy on the dancefloor, or through their singing on the improvised stages in some shebeens. Makeba could be considered such a shebeen queen, coming to national prominence singing as part of The Manhattan Brothers. Seutin’s Mimi’s Shebeen, however, takes the figure of Makeba as an ancestral archetype: the archetype of the mother, the musician, the shebeen queen, the political activist, the pan-africanist, the daughter, the wife, the lover and, perhaps most prominently, the healer and the exile.

Makeba was exiled from apartheid South Africa in the 1960s due to her outspoken political damnation of the oppressive apartheid regime, having her request for re-entry into South Africa after international touring denied and her citizenship eventually revoked. Makeba had been wanting to return for the funeral of her mother, herself also a isangoma. It is these two archetypes of the healer and the exile that Seutin renders Mimi’s Shebeen through. It feels important to note at this point, as I was such a close part of the process and eventual performance of the work, it is not my intention to provide an objective review or critical analysis of the work. My analyses come from a very subjective standpoint as someone who was embedded in the work from concept to realisation, as well as a South African who grew up listening to Makeba’s music, as well as a friend of the maker, Alesandra Seutin. It is from this place of hyper-subjectivity that I want to analyse the magical workings of Mimi’s Shebeen.

What I would like to focus on are the magical technologies and techniques Seutin applies in the process leading up to the work. During the rehearsal process, Seutin would guide us through a two-hour dance class every morning. We opened the class by standing in front of the windows of the rehearsal space, ensuring that we could feel the sun shining on our faces as much as possible. Seutin invited us to close our eyes and breathe in the energy of the sun or whatever reflections of sunlight we might be able to absorb in the capricious Brussels’ climate. Afterwards, we slowly made our way to the main body of the rehearsal space, greeting each other with warm hugs on, often, tired bodies. With smiles, with eye contact. This, I would describe as a subtle practice of thaumaturgy, or practical magic, as ceremonial magician4 Damien Echols defines it in his book High Magick5. Thaumaturgy is the category of magic that seeks to affect matter, to better our lives on the material plane through ritualised collaboration (or manipulation, but that word has colonial, anthropocenic connotations of ‘dominance over’ that I find arrogantly over-emphasises a human power over other more-than- human entities) with the material and immaterial realms.

In this exercise, Seutin was encouraging us to absorb the thermal energy of the sun, allowing our bodies to absorb and metabolise it for energy, and share the residual energy with others in the space, as well as with the space itself. In this way, we were invited to subtly enmesh our individual auric fields for the period of the day’s rehearsal process.

At the close of the rehearsal day, Seutin guided us through a subtle process of releasing the energetic enmeshment and attachments we have developed over the course of the day. This would often look like us holding hands in a circle, eyes closed, as Seutin guided us in words through a visual exercise where we imagined the breaths that we took as we stood eyes closed, hand-in-hand, as breathing in the energy of the day, taking with us what we individually believed would serve us for the rest of the day and the days to come, and then releasing the breath and, with it, leaving what energy of the day we believed could no longer serve us.

THEURGY AND THE WITCH’S INHERITANCE OF FAILING UPWARDS

You can’t do magick to affect someone else without changing yourself first.

— Damien Echols, High Magick

In Echols’ High Magick, he makes a distinction between two forms of magic: thaumaturgy (as I have discussed above) and theurgy. Theurgy refers to the branch of magic where we endeavour to achieve a state of oneness with divinity, God and/or the Cosmos (it really depends on your cosmological framework and what a ‘higher power’ means to you). It is a state referred to as ‘enlightenment’ in some esoteric fields of study and practice. Practices that help us to achieve this state include meditation and ancestral/deity worship, among many others. One performance work that I believe has a theurgical pursuit at its foundations is the work of Amanda Piña, EXÓTICA (2023).

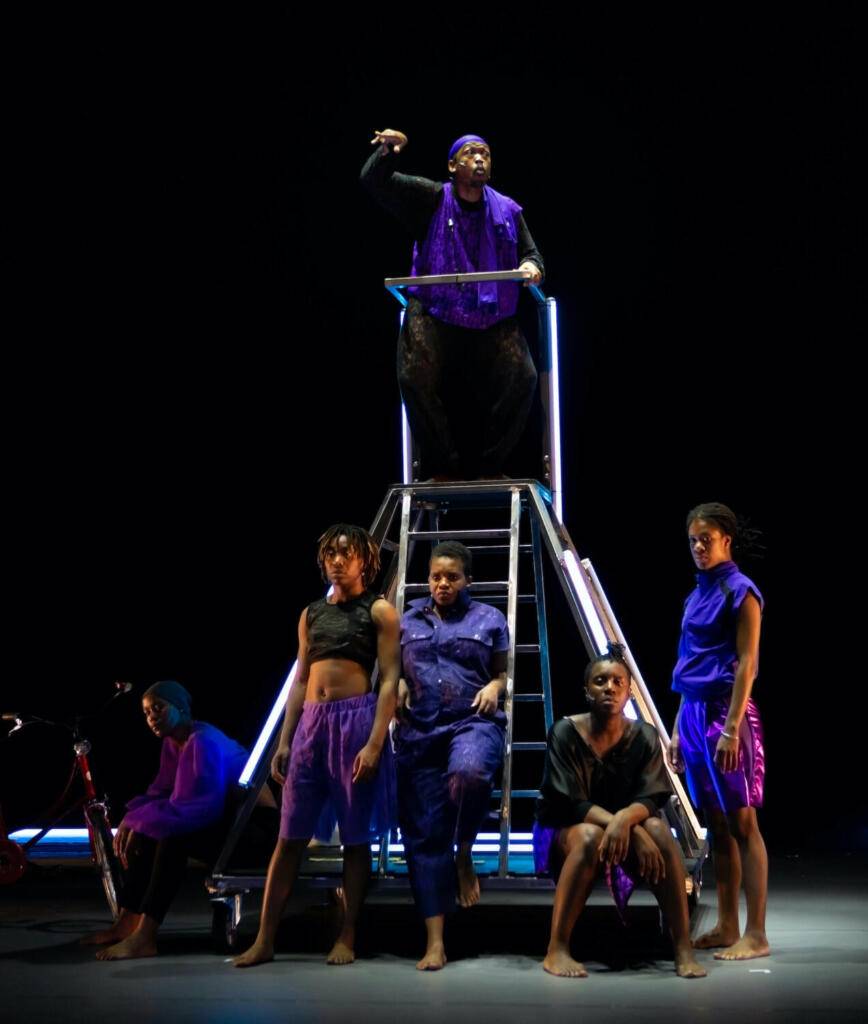

EXÓTICA is a dance performance made with five performers (Piña included) at various identity intersections from what is observable from the audience perspective. These five performers are tasked with inhabiting the spirits of four racialized performers from the 20th century who, in one way or another, found themselves being exoticized on the stages of Europe, namely: Nyota Inyoka, François (Féral) Benga, Leyla Bederkhan and Clemencia Piña ‘La Sarabia’. Now, in the present day, Piña proposes the five performers on stage as representatives of the inheritors of these exoticized performers’ legacies and tasks them with creating ‘an exuberant ritual conceived as a séance through which dancers evoke their spiritual ancestors and come into conversation with the audience’s gaze.’6

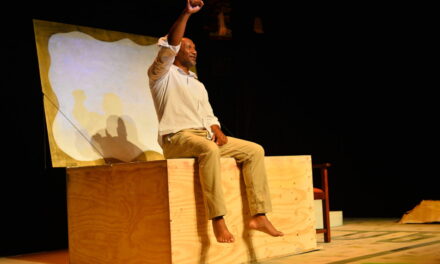

The Hero’s Journey of Anastácia, Carolina Maciel de França. Photo by Adel Setta.

At the beginning of the work the audience is greeted in the ostentatious Théâtre Royal des Galeries, replete with velvet seating and ceiling fresco by René Magritte, and a stage featuring the kind of ‘exotic’ tableau scenography one would imagine of the 20th century ‘exotic’ dance shows: a jungle/forest hybrid that wouldn’t be out of place in a staging of The Jungle Book. Alongside this impressive scenography we have, on opposite sides of the proscenium arch stage, altars with images of the soon-to-be-invoked ancestors. Soft billows of smoke from burning copal incense emanate from the altars which are decorated with flowers, plants, water and (perhaps) alcohol as is often the tradition with ancestral altars.

The opening image is, artistically, genius. It immediately visualises the frictions between the performers’ intent to work authentically with ancestors and ancestral dances and the exoticizing gaze imposed on them and their practices by the audience — as I looked over my shoulder from my seat in the second-to-front row of the theatre I could only see a sea of white faces illuminated by the front of house lights of the auditorium. The framework to revisit and reappropriate the exoticizing terms of engagement of the performers’ artistic ancestors is seemingly primed. Piña enters the stage and steps to the front periphery towards the audience and explains that this performance is not a representation but is, in fact, a ritual. The action on stage is real, not performed. And it is precisely in this proposal where the work begins to falter.

Anyone who is familiar with Piña’s work will know that she is an extremely astute and rigorous performance maker. Able to mould from the immaterial realms material, and embodied and performative proposals that are moving, bone-rattling, evocative, intellectually rigorous and spiritually sonorous. As such, it was with confidence in her significant performance-making abilities that I entered the theatre with an assuredness that if there was a performance artist qualified to work with the themes Piña proposes for EXÓTICA’, it is Piña herself. Unfortunately, the iteration I saw seemed to only re-perform the exoticization the artistic ancestors of the performers were beholden to. This is where I believe the theurgical trouble comes in.

Theurgical practices often require a stable and enclosed environment where all active participants have been invited into a specific and enclosed context where there is an agreement on what their shared intentions as participants are. And, though Piña invites us briefly at the opening of the work into a ritual of focusing our individual psychic attentions onto an object that she invites us to hold in our hands, this singular moment is not successful in making us active and informed participants in the ritual. For that, I would argue, somehow Piña would need to take us on the same journey all five performers have been on prior to presenting the work for us to fully appreciate our individual positionalities in relation to the ritual.

For many in the auditorium the night I watched the performance, their ancestors belong to the group of people who were active in the process of exoticising the artistic ancestors of the present-day performers. I would argue that this ancestral friction in the space is one of the root points of entry into the work. And, though it is acknowledged, it is not worked through. We are not meaningfully invited into the ritual outside of our roles as semi-active onlookers. But even the way in which we are invited to look is not completely framed. Are we witnesses? Are we culpable onlookers? Are we protecting the performers onstage with our attention? What are the stakes of our gaze? Should something happen to one of the performers what is our responsibility as watchers? Are we meant, even then, if this is a real ritual, to continue looking on? These questions are precisely, for me, where the success of the work lies. Though, for me it is not necessarily successful in its artistic endeavour to provide a context for invoking spirits and exorcising those that need to be released from this plane of reality, it succeeds in opening up a pressing question for our time: exactly what is required to do this kind of ancestral work where, for some, our ancestors are the historical victims and, for others, our ancestors are the historical perpetrators7. It is a foundation of magical practice (as with the scientific method) to try, to fail and to continue failing upwards until our hypotheses provide congruent conclusions. Though EXÓTICA’s hypothesis comes up lacking via its execution, it remains a maverick example of extremely complex artistic and magical practice.

THE TRICKSTER AND THE MANY FACES OF ANASTÁCIA

In 2022, I was invited by the artist Carolina Maciel de França to join her work The Hero’s Journey of Anastácia as a dramaturge. De França and I were familiar with one another and one another’s work but, according to de França, her request for me to join the work was more intuitive than ‘rational’ 8. This intuitive invitation was irrefusable to me and my penchant for mysticism (blame it on my sun in Pisces). It was de França’s intention to use the framework of ‘the hero’s journey’, popularised by the literary scholar Joseph Campbell in his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, to investigate the living memory of the Brazilian saint Escrava Anastácia: Anastácia the Enslaved9. De França herself coming from Brazil and having had a long history with the representation of Anastácia and the various diverging accounts of her story wanted to work with the story of Anastácia to engage themes around mysticism, truth, misogynoir, memory and, potentially, healing. It was with these intentions in mind that I raised with de França the archetype of ‘The Trickster’.

The Trickster is a mythological motif depicted through various characters throughout world mythologies and religions10. It is a figure, whether deity or human or more-than-human, that uses their immense intellect and secret knowledge to defy conventions, play tricks, lie, steal and, most ubiquitously, cross the borders of the known and unknown worlds. One of the most popular figures in Western mythology of the trickster archetype is the Greek god Hermes, who was associated with themes relating to information and secrets. He was the patron of thieves, merchants, orators and the inventor of lying. He was also charged with the responsibility of guiding souls into the afterlife and, one of the few gods who could travel between the worlds of mortals and the worlds of the immortals (the Upper and Lower worlds). As such, when we look astrologically at the natal charts11 of individuals, the placement of the planet Mercury tells us a lot about the native’s12 cognition and communication styles, as well as their cognitive boundaries. Upon providing de França with an astrological reading as part of our dramaturgical collaboration, it became clear that Mercury, the trickster, was a very important part of her way of dealing with information and the crossing of borders and boundaries. The trickster would be our patron deity for the process of The Hero’s Journey of Anastácia.

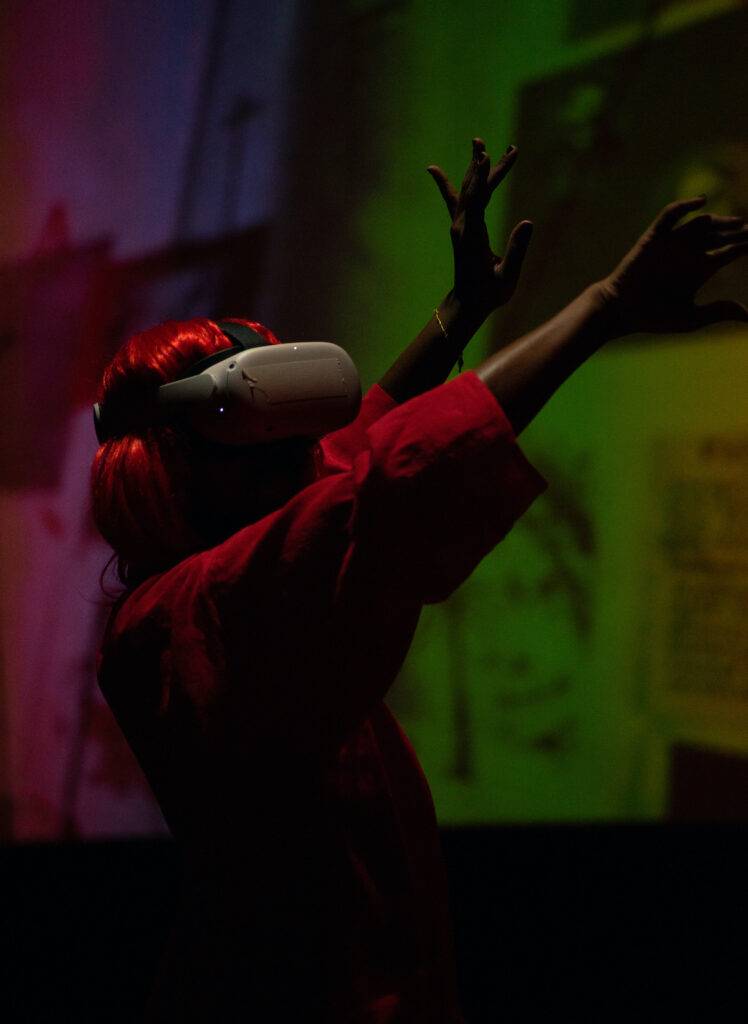

The Hero’s Journey of Anastácia, Carolina Maciel de França, photo by Adel Setta.

In The Hero’s Journey of Anastácia, de França plays the role of the trickster: the holder of immense knowledge, of converging and diverging knowledge regarding the figure of Anastácia the Enslaved. There is the version where Anastácia is a saint who led a rebellion of enslaved people during the Portuguese colonisation of Brazil. There is the version of Anastácia who was herself an enslaved person from Africa. There is the version where Anastácia is, in fact, the daughter of a Portuguese coloniser and an enslaved African. There is the version where Anastácia possessed supernatural healing abilities. Anastácia the Hero; Anastácia the Rebel; Anastácia the Saint; Anastácia the Healer; Anastácia the Witch; Anastácia the Temptress; Anastácia of a Thousand Faces. What began for de França as a process of trying to discover the absolute Truth, led down a path where the only truth she could find was the truth of her own story: the Brazilian daughter raised in Flanders. The artist with a penchant for mischief and rigorous research. The mother raising a child between worlds. The woman fed up with limited narrative possibilities for women who run with the wolves. The intellectual who prioritises intuition over reason (and sometimes the reverse). The Feminist Killjoy who wants both a room of her own and a wide-open space where stories can be shared and told and contradicted and refuted and remodelled. The Hero’s Journey of Anastácia is not a straight road but, instead, an ever-widening gyre.

For me, de França represents the trickster in her most benevolent state: a guide across the boundaries of the living and the dead who promises no peace, but merely a light by which we can walk the winding paths of what it means to be in the world but not of it13. De França invites us on the witch’s path. The path where we are invited to be rigorous and indiscriminate in our pursuit of knowledge, and equally rigorous in how it is that we apply the knowledge that we find. Whether for healing, lying, destruction, resurrection, insurrection or simply for the joy of knowing. What we do with what we find on our path is the ultimate articulation of that nefarious gift bestowed upon us by whatever power we believe endowed us with consciousness: choice.

What I believe the above is an indication of is far from a trend, and more of an extension of a legacy. All three works above situate themselves at the crossroads of history and magic. All asking: what shall we do with all we have inherited? How shall we cultivate these strange fruits? Both magic and art (however similar; however distinct) afford us the opportunity not only to reflect on our shared histories but also to become empowered actors in the stories of history. And, through our actions, making us accountable not only for ourselves but one another as our acts weave together to form the action of history. The great tapestry of doing and undoing that we might call something like God.

The title of this essay comes from the Buffy Sainte-Marie song of the same title.

- https://starhawk.org/the-magical-battle-of-this-time/

- These qualifying statements are reflective of my personal understanding of these words.

- Duffy, M. (2013). ‘Reproductive Labor’. In Smith, Vicki (ed.). Sociology of Work: An Encyclopedia. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. pp. 1213ff.

- Ceremonial magic is a school of ritual, Western esotericism popularised by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.

- ‘Magick’ is spelled here with a ‘k’ to differentiate the ritualised systems of esoteric practice and study from ‘stage magic’. In the West, the popularisation of this spelling is attributed to the 20th century esotericist Aleister Crowley.

- From the programme note of the premiere of EXÓTICA at Kunstenfestivaldesarts in Brussels, 2023.

- This distinction of ‘victims’ and ‘perpetrators’ is very superficial. It is not my opinion that the dialectic of ‘perfect victims vs perfect perpetrators’ is constructive but I use it here for the sake of brevity. For more nuanced engagement on this I propose the work of Sarah Schulman, Conflict Is Not Abuse and this article from TIME magazine: https://time.com/6183505/amber-heard-perfect-victim-myth-johnny-depp/

- The dialectic between intuition and rationality is one of the most recurring, frictional and exciting spaces of all magical practice, in my opinion.

- I use the arguably imprecise translation ‘Anastácia the Enslaved’ here to deviate from the more common and, arguably, disempowering translation ‘Anastácia the Slave’.

- A great definition for religion and mythology can be found via Joseph Campbell. ‘My favourite definition of mythology: other people’s religion. My favourite definition of religion: misunderstanding of mythology.’ (Campbell, Thou Are That, p. 111 [in:] James W. Menzies, True Myth, s. 25)

- A natal chart is essentially a snapshot of the sky and the planetary positions when one is born.

- This is the term used in astrological practice to refer to the owner of the natal chart.

- This is a paraphrasing of the Bible verse John 17:11, 14–15.

This article appeared on Etcetera on September 15, 2023, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, please click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kopano Maroga.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.