Health and government officials around the globe are slowly and ever-so-tentatively moving to relax lockdowns due to coronavirus.

In Canada, where the possibility of health-care collapse seems to have been averted (for the time being), some are beginning to ask questions other than “when will the pandemic end?” Instead, they’re turning towards “how will we move forward?”

Young people have some answers that warrant our attention. Over the past five years, through my collaborative ethnographic research with 250 young people in drama classrooms in Canada, India, Taiwan, Greece and England, I have gained remarkable insight into these young people’s experiences and assessments of the world.

I found crisis after crisis being shouldered by young people. Through their theatre-making, they documented their concerns and hope, and they rallied around common purposes. They did this despite disagreement and difference.

Beyond simply creating art for art’s sake, or for school credits, many of the young people I encountered are building social movements and creative projects around a different vision for our planet. And they are calling us in. This is an unprecedented moment for intergenerational justice and we need to seize it.

Students in an after-school drama club in Athens rehearse their performance about the refugee crisis, March 2017. Photo by Kathleen Gallagher.

Crises are connected

I have had an up-close look at how seemingly disparate crises around the globe are deeply connected through divisive systems that don’t acknowledge or respect youth concerns. I have also learned how young people are disproportionately affected by the misguided politics of a fractured world.

In England, young people were burdened by the divisive rhetoric of the Brexit campaign and its ensuing aftermath.

In India, young women were using their education to build solidarity in the face of dehumanizing gender oppression.

In Greece, young people were shouldering the weight of a decade-long economic crisis compounded by a horrifying refugee crisis.

In Taiwan, young people on the cusp of adulthood were trying to square the social pressures of traditional culture with their own ambitions in a far-from-hopeful economic landscape.

Second-year theatre students at the National University of Tainan, Taiwan, warm up with drama activities, November 2016. Photo by Kathleen Gallagher.

In Toronto, the youth tried to understand why the rhetoric of multiculturalism seemed both true and false, and why racism persists — and, in so doing, they spoke from perspectives grounded in their intersectional (white, racialized, sexual- and gender-diverse) identities.

They embraced the reality that everything in popular culture may enter a drama classroom. But they responded to current news stories — like the 2016 presidential debates in the United States — by saying that they had different and more pressing concerns, like mental health support and transphobia.

Hope through creative work

Today’s young people are a generation that has come of age during a host of global crises. Inequality, environmental destruction, systemic oppression of many kinds weigh heavily.

I found a youth cohort who, despite many not yet having the right to vote, have well-honed political capacities, are birthing countless global hashtag movements and inspiring generations of young and old.

These marginalized youth are aware that their communities have been living with and responding to catastrophic impacts of crises of injustice and inequalities long before now.

Practising hope

How do these youth live with their awareness of global injustices and what these imply for the years ahead? We learned some disturbing things: as young people age and move further away from their primary relationships (parents, teachers, schoolmates), they feel less optimistic about their personal futures.

But in terms of hope, we learned something very recognizable to many of us now: many young people practise hope, even when they feel hopeless. They do this both in social movements they participate in and in creative work they undertake with others.

This is something we can all learn from. In Canada, we are maintaining social distancing as a shared effort. Acting together by keeping apart is how we are flattening the curve, as all the experts continue to tell us.

We know that in communities around the world, government leadership matters enormously. But citizens, social trust and collective will matter at least as much.

Young people from the Canley Youth Theatre, based in Coventry, England, rehearse their play ‘Museum of Living Stories,’ based on their personal memories, June 2016. Photo by Kathleen Gallagher.

Polarization

In this pandemic, institutions, like universities, businesses and individual citizens have stepped up remarkably in the interests of the common good and our shared fate.

However, Jennifer Welsh, Canada Research Chair in Global Governance and Security at McGill University, argues that the defining feature of the last decade is polarization, existing across many different liberal democracies and globally.

Along with this, the value of fairness has been deeply corroded because of growing inequality and persistent historic inequalities we have failed to address, like Indigenous sovereignty and land rights in Canada.

In the context of the rise of populist politicians and xenophobic policies globally, and also the rise of the most important progressive social movements in decades, my research has taught me that in this driven-apart, socio-economic landscape, the social value of art has never been more important.

People are making sense of the inexplicable or the feared through art, using online platforms for public learning. Art has become a point of contact, an urgent communication and a hope.

But some are still without shelter, without food, without community and without proper health care. The differences are stark.

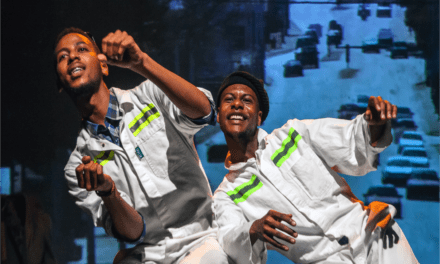

A Grade 12 drama class in Toronto performs their play about youth mental health and trans solidarity for their school community, December 2016. Photo by Kathleen Gallagher.

Moving forward

Arundhati Roy has imagined this pandemic as a kind of portal we are walking through: we can “walk through it lightly … ready to imagine another world.” We can choose to be “ready to fight for it.”

It’s time to put global youth at the centre of our responses to crises. Otherwise, young people will inherit a planet devastated by our uncoordinated efforts to act, worsening a crisis of intergenerational equity.

We should, of course, develop a vaccine and, in Canada, stop underfunding our public health-care system. But we must also flatten the steep curves we have tolerated for too long. For a start, we could act on wealth disparity and social inequality.

But our response to the pandemic could also illuminate new responses to fundamental problems: disrespect for the diversity of life in all its forms and lack of consideration for future generations.

Youth expression through theatre and in social movements are valuable ways to learn how youth are experiencing, processing and communicating their understandings of the profound challenges our world faces. How powerfully our post-pandemic planning could shift if we changed who is at decision-making tables and listened to youth.

This article was originally posted at theconversation.com on May 14, 2020, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kathleen Gallagher.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.