The Ottawa Little Theatre’s production of An Inspector Calls, the classic mid-20th-century drama by British writer J.B. Priestley and directed by Jim McNabb, is one which leaves something to be desired for the more socially-conscious viewer.

As a performance given by actors, it is not entirely unsuccessful; the laughter elicited from the audience at even odd moments during the show attests to this. The task of meaningfully transmitting Priestley’s message of social responsibility for others, however, is where McNabb’s vision falls short.

Set in April 1912, the play begins with a scene of celebration at the home of the haughty, upper-middle-class Birling family; what they are celebrating is the engagement of their daughter Sheila to the son of a rival family, the Crofts.

The attitude of callousness and disregard for other people which Priestley later condemns is fully manifested by the family patriarch Arthur, who declares that “A man has to mind his own business.”

Then, almost in an act of karma, the party is cut short by a visit from a mysterious inspector who has come to question the family about the suicide of a young working-class woman named Eva Smith. At first, they are incredulous: what’s this tragedy got to do with them? As it turns out, each family member has to contend with their role in the downfall of someone less privileged than they are.

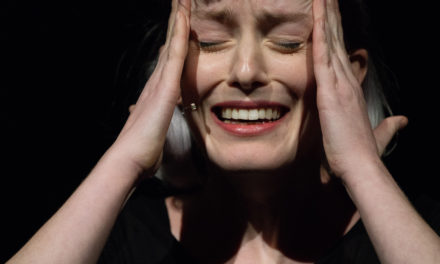

The strongest performances come from the Birling children, Sheila (Katherine Williams) and Eric (Jamie Hegland). Both actors are able to effectively capture the personalities of their characters (a preppy yet ultimately defiant Sheila, an irresponsibly alcoholic Eric) and express emotion in a way that is convincing. Their vocal projection is wonderfully clear, and British accents well-practiced.

As the family patriarch, Roy Van Hooydonk gives a respectable performance. Although his accent is not quite as convincing as that of Williams’ and Hegland’s, Van Hooydonk is able to clearly express Arthur’s greed and callousness, letting the audience know exactly what kind of person his character is.

Although Janet Rice gives a genuine effort as Arthur’s wife Sybil, her character only truly comes into her own when she’s being grilled by the inspector about her part in Eva’s death. For the most part, Sybil is understated and less forceful compared to the others around her.

Portrayed by Guy Newsham, Sheila’s fiancé Gerald Croft also comes off as underwhelming. One thinks that this character may have had more of an impression if Newsham relaxed a little or diversified his facial expressions.

The inspector himself, portrayed by veteran actor John Collins, provides a presence that is notable yet tempered by the production’s more humorous tone. In grilling the Birlings about their past misdeeds, Collins is an effective interrogator.

His role as the play’s moral center, though defined, is made to be less significant; his lecture to the family on social responsibility, ending with the declaration that “We don’t live alone,” seems rushed, not allowing for the full gravity of his sentiment to be felt by the audience.

Another anticlimactic moment occurs when the inspector declares to Sheila that, “We all share responsibility” for Eva’s suicide; the revelation is made abruptly, without being allowed to meaningfully sink in.

It is at moments like these where McNabb’s direction falters: moments which should be reflective for both the characters and the audience are made light of or simply glazed over in favor of the play’s more comedic elements.

Given the play’s sharp critique of social inequality and disregard for the less fortunate members of society by those more privileged, one would expect McNabb to play these themes up in order to give it special relevance to the current moment. Instead, this production of An Inspector Calls appears more like a dark comedy – much to the detriment of its original socially-conscious aims.

This post originally appeared on Capital Critics’ Circle on January 12, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Natasha Lomonossoff.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.