The performance follows four women in different parts of Ukraine, at various distances from the frontline and allows them to tell their pre and post-February 2022 stories.

Abrupt opening? It follows the spirit of This Is Our Home – Ukraine, which, in turn, seems to consciously trace back the steps of the ongoing European conflict, which started without any warning, on a mere February day. Rough, tough, yet emotional and touching, Yana Salakhova and Rodolfo García Vázquez’s production reminds its audience of two moments in the recent past which reshaped humanity to its core.

With dim light and scenes marked by absolute loneliness on the screen, the story unfolds in a confession-like atmosphere, disturbed only by the sound of shelling or by the memories, video-journals almost intrusive in such contexts. Given the situation outside the theatrical environment, the concept of realism attains new valances, theatre not mirroring the world, this time, but helping a reality catch tangible shape in front of the viewers eyes.

Through cleverly-integrated symbols, that never lose their importance as meaning-deprived objects, either, lighting, space changes, and video insertions, the show manages to create the impression of a normal performative chronology, reducing the impact of the return to online theatre productions and becoming more than a means of artistic expression, but rather a meeting point of art-related individualities, communicating on a(n unfortunately still) fervent subject. The apples, symbol that can be subjected to a Biblical interpretation, is recurrent in both metaphorical and physical forms, stretching the parallel between the pre- and post-invasion life into a metaphysical link between the mental realm of the character (personal past, memories of the relatives left near the frontline, dreams of a better future) and the seemingly never-ending winter of the place she is seeking shelter in. The couple of toys used to exemplify the house analogy of the Russian war on Ukraine are, in turn, all that is left of the image of the Child, now crying in their mothers’ arms on the trains to freedom, while their fathers remain in the homeland, fighting for their country, or being forced by circumstances to start their childhood all over again, after all they have experienced. In a similar, almost consequential manner, the concept of “luggage” materializes itself and becomes, gradually, only a small backpack, inversely proportional to the distance the characters have now placed between them and their old life.

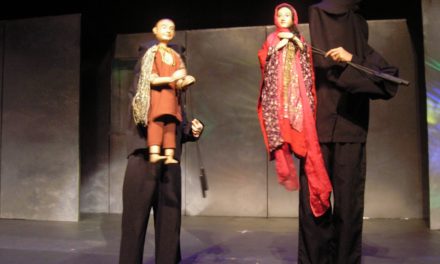

Natalia Titiyova in This Is Our Home – Ukraine, Directed by Yana Salakhova and Rodolfo García Vázquez. Produced by The Red Curtain International, 2024.

On the side of the technical aspects, however, the matters did not develop with the fluidity one might be used to from on “on-site” theatre – the lighting, operated individually by each actress, was not disturbed by interferences from the internet connection, allowing each character to have a visual environment that suggests they are in a neutral space (hence the black background), at the same time safe and not, as one can understand from the sounds of missiles and drones flying above them and exploding in the near vicinity. Even so, the convention is still broken a couple of times, giving the spectators insight into what lies behind the life the four women chose to publicly present – a frozen apple tree and a toy-house made with only a couple of magnetic bricks – symbolic relics from a (not so distant) peaceful past.

Yana Salakhova in This Is Our Home – Ukraine. Directed by Yana Salakhova and Rodolfo García Vázquez. Produced by The Red Curtain International, 2024.

The use of videos, however, reminded each and every one some of the reasons why online theatre was living on the border with spite during the pandemic – most of the time a proof of the laws of physics attesting that light travels faster than sound, the images were moving ahead of the music, periodically stopping and starting again after having skipped several sequences… Regardless of how well managed the technical side was, the internet connection of the audience members also played an important (may I say vital?) role…

At once with the technological difficulties, the live interpretation feature (what actually enabled the borderless attendance of the production) interfered, in turn, with the complete and proper theatrical experience. The impact of this Zoom feature could be felt in the repetitions (although they could also be blamed on the script [?], had it not been for the language barrier), caused in part by the speech pace of the actresses, in part by what felt like a reduced number of rehearsals in the complete format of the production or even by a personal difficulty of each translator to cover up the Ukrainian synonymies in English. This created a feeling of déjà écouté, which, alongside the rest of the technical impediments, became annoying to the audience member (in this case, to the listener).

In spite of the previously-mentioned incongruences, the relations between the characters, skillfully constructed even in the context of (postbrechtian) distanced acting, are functional even beyond the screen. The convention that they are communicating online for the sake of letting each other know they are still alive played out realistically and with a logic that extended beyond the necessity of online theatre during a pandemic or a war and reached the insurmountable need for community and communion, even in the darkest (see the background color of each of the performers) of times.

Accidentally, the quadripartite storyline was continued after the fall of the curtain (the “thank you” typical for Zoom theatre, which assimilates a performance to a – more or less corporate – presentation) with the emotional interventions of the Ukrainian spectator based in Germany, the fifth woman telling her story of de-rooting and forced identity reconfiguration in the context of having to leave her country behind, in the hands of missiles and drones. The realism of the performance, thus, becomes Reality, and the fourth wall, of a physical and electronic nature this time, loses its theatrical relevance by becoming one of a highly protective nature.

Vladyslava Kryzhna in This Is Our Home – Ukraine. Directed by Yana Salakhova and Rodolfo García Vázquez. Produced by The Red Curtain International, 2024.

The discussion, opened not only by the performance or by its context (online performance, Russian invasion of Ukraine), but also by the previous questions asked – the development of a song for- and in the name of peace – quickly developed into an in-depth inquiry about the validity of theatre as a means for change. The mutually agreed answer was, nevertheless, not what the audience would have hoped for, as the most compelling “solution” did not come from the sphere of dramatic arts, but rather from music, named “the farthest-reaching art,” although theatre did gain the title of “the oldest art that developed independently [and concomitantly, may I add] in multiple geographical spaces.”

Online theatre is, indeed, and in a similar manner to physical performance, platform specific, which enables distinct relations between the audience and each of the mediums. On the phone, in this case, the experience is slightly more difficult to control, due to the swiping in between speakers and full-panel mode, compared to the laptop-bound experience. Other several technical difficulties (such as the people who interfered – the woman who arrived later and also had her camera on) that persisted, in spite of there being an extra account specifically for this matter made it even more problematic to focus on the experience per se, rather than on the constant association with the times when online theatre was a necessity.

“A theatre without geographies,” as the organizers said, can be achieved only with the dissolution of the needs for physical presence, as one’s relation with time is inherently subjective, but the paradigm of online theatre shifting from “curse” to “blessing” (with the irony implied by the contexts in which we made use of this type of performing art) is still far from being translated into normality. Even three years after the first urgent need to resort to digital means of theatrical exposure, the hypostasis of homo digitalis is still a question of appetence, rather than of habit.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Teodora Medeleanu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.