It’s late on a Friday night in July and I’m setting up my kitchen for co-hosting an online puppet cabaret, Slamalicious, with the Calgary Animated Object Society (CAOS). This raucous, interactive slam with a pirate theme is hosted by clowns and will feature new works by a roster of both established and emerging puppeteers.

Inspired by poetry slams (minus the competition aspect), puppet slams originated in the late ‘70s to showcase new work and entertain audiences. Today, their popularity holds even as they’re shifting online during the coronavirus pandemic.

My workspace is my kitchen table and I’m doing my best to achieve some stage lighting with a desk lamp.

With my left hand, I’m manoeuvring my desktop to follow artist introductions and, as one of many performers on the Zoom platform, my right hand is occupied with a puppet. Technicians run the show from Calgary, from where they manage hosting, sound and control video sharing. Prior to showtime, I overhear a technician joke, “We’re using this in all the ways it wasn’t built for!”

As theatre artists, we have to get innovative in how we do live to perform during a pandemic. However, physical theatre performers (whose primary mode of storytelling is through movement) have always had this resiliency.

Puppets Woody Peg the pirate and Salty the seagull were created by puppeteer Juanita Dawn. (Juanita Dawn), Author provided.

Not just for kids

Much like the Commedia dell’Arte troupes of the 16th century, clowns, puppeteers, mask performers and mimes can make theatre anywhere. We are street performers at heart: just give us an audience and a platform. (Virtual will do!)

Puppetry as an art form forged ahead during the pandemic because puppeteers are creators who do it all. They are designers, storytellers, performers, sound composers and now filmmakers capturing puppetry for online audiences.

Online participants dance at Slamalicious. (Calgary Animated Object Society).

Puppeteers are showcasing their work via a multitude of online puppets slams, such as the Brooklyn, N.Y.-based Great Small Works and Puppeteers of America’s National Puppet Slam, based in Minneapolis.

And if you think puppets and clowns are only for children, think again. Our puppet slam contains political pieces dealing with toxic masculinity, racism, economic inequality and corrupt politicians. Amid the uncertainty and pain in the world, puppeteers and clowns are jesters who can get away with telling the hard truths and inciting much-needed cathartic laughter.

Cabaret tables move to chat windows

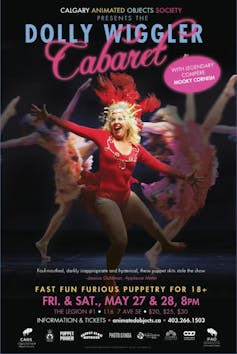

What spawned Slamalicious was the Dolly Wiggler (a term coined by marionette master Ronnie Burkett) — an adult puppet cabaret known for being “wild, weird and always entertaining.”

Every May, for almost 20 years, the Dolly Wiggler Cabaret has given puppeteers an opportunity to showcase new work. Prior to the pandemic, the performance has been held over two evenings at the Royal Canadian Legion in downtown Calgary and attended by hundreds.

Dolly Wiggler Cabaret poster featuring renowned Canadian clown Mooky Cornish.(Calgary Animated Object Society), Author provided.

The show clocks in at around three hours due to the large roster of artists showcasing new work and it’s hosted by professional clowns who interact with the audience. It’s a highly communal live theatre event, where the audience is seated cabaret-style at tables and encouraged to mingle with the artists during the intermissions.

When COVID-19 hit, CAOS’s artistic director, Xstine Cook embraced the challenge of moving the Dolly Wiggler online. CAOS managed to replicate the communal atmosphere through Zoom: the platform’s “breakout rooms” became mingling at the bar and the chat window became the way performers engaged with audiences at their cabaret tables.

Attendance-wise, it was business as usual: the online performances had the same number of attendees as the in-person shows in previous years. This is the current status for artists who make original work; we make the situation work to continue making work. Puppeteers are self-sufficient and adaptable, and CAOS shifted the Dolly Wiggler event by taking it online. After this success, Slamalicious was born.

Clowns ready to cover

Back to my kitchen. Before the show goes live, I still have to get into costume as Ms. Sugarcoat, a naively optimistic public school teacher. I am co-hosting with Xstine Cook. She will be stepping into her clown character, Unca Grampa, who is an inappropriate old man with a penchant for the ridiculous.

As hosts — or in performance terms, compères — of the event, we not only introduce the performers, we perform original clown material and our own puppetry pieces. Also, we improvise, because if anything technical goes sideways, the clowns need to be ready to cover.

Puppeteer Jennifer Bain, right, and her puppet Carl T. Morgan, left, performed at Slamalicous. (Jennifer Bain), Author provided.

The puppeteers who are sharing their work in Slamalicious have had the option of performing live or sending videos of their work. As a co-host, I’m live the whole time in front of a real-time audience. But unlike when performing live in a theatre, now my audience is in small boxes, filling my whole screen.

And just like with live performing, my stage fright kicks in. I have to teach this audience choreography to a pirate dance. What if these adults aren’t game to play?

The show starts and I see an audience sporting eye patches, striped shirts and pirate hats. Clearly, adults need to play too. The evening ends with dancing in our Zoom boxes, many audience members holding up their own puppets at home, making my desktop look like the opening of The Muppet Show.

The platform where we engage with the audience may change, but we’ll always channel the spirit of the Commedia dell’Arte street performers of the 16th century.

This article was originally posted at theconversation.com on August 30, 2020 and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Alice Nelson.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.