Ashley Tata is a Brooklyn-based director and maker of multimedia works. I had the pleasure of speaking with Ashley about previous projects, upcoming pandemic productions, and future goals.

Victoria Isotti: For readers who may not already be familiar, can you tell me about yourself and your work?

Ashley Tata: I’m a director. I’d been directing theater and a lot of opera up until the shutdown, principally contemporary operas written by composers and librettists who are still alive. Much of the work was multimedia. When I look back, the first real piece I directed was with a close collaborator when we were in high school. We adapted a silent, black and white film to the stage. We did it all in black and white makeup and gray-scale scenic design and integrated video by filming fellow actors and then digitally aging that film and editing it into the archival film that we were referencing. The piece was performed silently with super-titles for dialogue and was through-scored with a kind of temp score. There wasn’t a lot of theater that I was going to see other than the theater that we made, so I didn’t really know what we were doing. But I realized that integrating media into the work that I make has always been a part of what I’ve been doing.

VI: You have been so busy during this pandemic. The first pandemic project you worked on was Caryl Churchill’s Mad Forest. Can you describe what that experience was like?

AT: Well, first, I do just want to say that I’m very lucky for that. I am happy to keep working on these projects and I see it as one interesting problem after another. Mad Forest is a perfect example of being in a situation where the artistic director and producers were willing to take a risk. It was pretty late, a lot of other schools already shut down, a lot of projects were already canceled. Gideon Lester [the artistic director] had called me and very generously said we can either payout you and the design team even if we decide not to do a production, or you could try to figure out a way to keep making it. I knew that if we were going into a shutdown I needed to make something, and had a suspicion that my colleagues would need to make something. Gideon said he heard that there’s this company doing a radio play, but Mad Forest has so much to do with how one expresses when they cannot speak, so I said no, we can figure out how to do this online. My next call was to the design team because I wanted to make sure that each of the designers had a way to stay involved. This is where it’s important to surround yourselves with people who are willing to say, “I have no idea what this is going to be, but I’m interested in the problem.” I then talked to the students to see if they would be interested in such a thing. Within a week Bard had shut down and the young performers showed up to the Zoom rehearsal a week later.

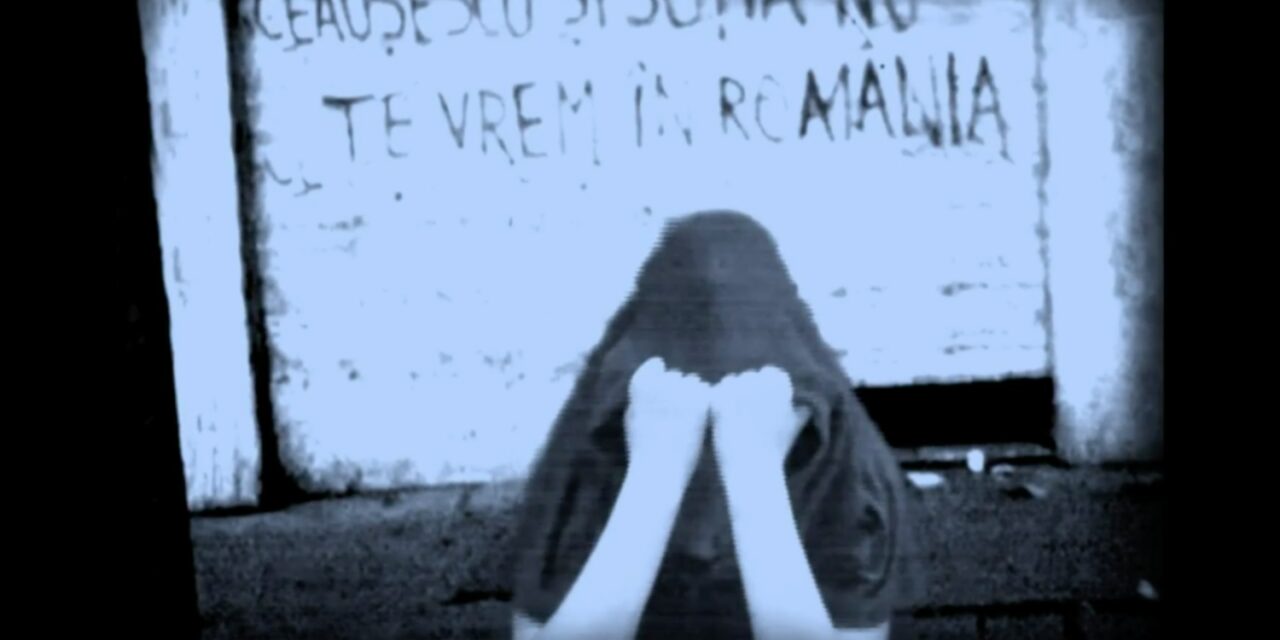

I had a very strong sense of what it could look like. I think that part of that is because of my work with video images as layers in a live theatrical setting, but it’s also because of the story that’s told. The history of [the Romanian Revolution] was captured on camera so there’s this whole documentation of it and it looks similar in definition to what Zoom cameras capture, so there was an aesthetic integrity that I felt was of the world of the piece. And there are also themes of surveillance which become a thread of the relationship between the performer and the camera and the audience relationship to these and the event. In weird timing, a colleague who I’ve worked with for many years saw a Facebook post that we were moving online and called me. So we brought on our video designer, Eamonn Farrell, and Andy Carluccio, a student of Eamonn’s who was in his senior year as an undergrad, to figure out a way to make Zoom work more like a mixing board. I started working on the script by assigning a different camera number to each of the actors and editing the script like a shot list. The engineer would spotlight each actor using the dropdown Zoom “spotlight” feature which was pretty cumbersome. During the second week, Andy sent a text message at three in the morning saying he figured it out. So we were able to incorporate this modification (now called Zoom OSC) that was able to make Mad Forest operate more like a live television broadcast.

The first performance at Bard was in April of 2020. I was asked to do it again by Jeffrey Horowitz at Theatre for a New Audience. There was a month between the Bard and Theatre for a New Audience performances and in that time Andy and the team kept figuring things out. Like this double green screen, where we could add one actor into the square of another actor. We could only do it for one scene, the scene with the ghost. When we first rehearsed that we didn’t tell the performers that it was going to happen, so it was a surprise. It was the first time we had seen two people in a square together in a while. It was just really, really thrilling.

Magos Herrera performing in a video of Rojo Sol accompanied by Kevork Mourad’s live painting captured at a rehearsal for Con Alma.

VI: You said that you directed a lot of operas before, and you’ve continued to work on musical projects during the pandemic, such as Con Alma. Can you tell me about this experience?

AT: There are two kinds of different music projects I’ve worked on this past year, which I’m so grateful for: socially distanced in-person performances and “hybrid” performances that mix live and pre-recorded content. Of the first was a socially distanced production of John Luther Adams’ 10,000 Birds, which we did outdoors at PS21 in upstate New York with the ensemble Alarm Will Sound. That first music rehearsal, there was just something about listening to music with the body. Any opportunity to be near the instruments or the vocalist is a completely different experience.

Then there is Con Alma with Paola Prestini and Magos Herrera. They made an album during the pandemic. They were able to work with composers, vocalists, and musicians all over the world. It’s a very immediate and beautiful response to a moment, deeply exploring what it really is to connect with each other as artists and the belief that this connection expands to people from all walks of life. They wanted to release the album and do a live event. The event is this mix of pre-recorded music videos, live music performances and interviews, and live drawings by visual artist Kevork Mourad. I’ve become way more invested in the audience experience because you take for granted that they will feel part of that audience group. It’s important to me to create a collective experience. With Con Alma, we were broadcasting to television stations in Mexico and in the Northeastern U.S. We were able to have people send tweets to a specific hashtag or handle, and they would see their own tweets being broadcast on the screen. That was our way of letting the audience know that we see them.

VI: You have two upcoming projects, The Wildness and Red Giant. How are these projects going?

AT: So The Wildness is Sky Pony’s punk rock performance project. There is a desire to make this project again, and it feels appropriate for right now. The Wildness is about ritual, about voicing fears and concerns and anxieties about the future and being in community for that experience. Figuring out how to do that online is difficult, but we’re working on restructuring the script and presenting it for an audience who is invited into a Zoom space. It will feel like a large Zoom meeting with music and video. It involves light audience participation, where I hope that the audience feels comfortable unmuting at the right time to offer things. There are some instructions for props that we will ask people to have on hand if they want to engage in the full ritual. The music is really great and they’re incredible performers. I’ve been remotely directing the creation of music videos as part of the content for this work. What’s really thrilling is those moments where you have this idea and you try to put it in words, and then something comes back to you and it’s more moving than I had originally imagined.

Red Giant was on the calendar as my next project from the before times. It’s an opera that centers around three people in space and they wake up from a hibernation period. There’s the sense that it’s very claustrophobic because it’s three people in a capsule, but they also express intense alienation from each other. We get the sense that they had to leave Planet Earth because we weren’t going to make it, so it’s another one of these pieces that works now. I think we can figure out how to do it online in a way that dramaturgically supports the content.

A third piece that I’m developing is a hybrid piece that’s moving into sound installation and augmented reality. One of the things I’m interested in is trying to bridge the gap between devices and terrestrial performance. I’m trying to build a terrarium that contains a work where this is inevitable.

VI: You also have two residencies right now, with Brooklyn Academy of Music and Coffey Street, both of which started during the pandemic. How has that been?

AT: The two residencies were offered before the pandemic and have been taking place during. Since 2012, I would either be on projects as an assistant or associate director or direct and develop works instigated by other artists. I had stopped generating my own work, and recently I started wanting to create my own work again. I was really appreciative of both BAM and Coffey Street for considering that if given space and time, I could start getting something going and bring in a lot of other collaborators to that space. The thing that’s been really inspiring is seeing my colleagues create whole new ways of making and thinking. At Coffey Street, we are engaged in a conversation about creating space for people who are in this phase of their artistic life where they are generating work but need the space and time to actually develop it. There’s a lot of presenting opportunities in this country and in this city, but there isn’t a lot of space to bring designers together and make a piece, and to invite an audience to see something that’s more design-forward. So this is exciting.

Scene from Mad Forest Pictured (from top left): Andrew Omar Crisol, Azalea Hudson (from middle left): Ali Kane, Lily Goldman, Yibin (Bill) Wang (from bottom left): Tim Halvorsen, Violet Savage

VI: Going forward, what are your hopes for the future?

AT: I will continue to be an advocate for live performing arts in this country, saying that it does serve a necessary function and that there’s an intrinsic value to the arts as a whole. Part of that work is continuing to show up and instigate collaborations with artists. What I love about the work that I’m finding myself making is it puts me in a collaborative community with people who don’t have shared life experiences with me. I love that people are reaching out to me and I am reaching out to other people. And there’s also a group of collaborators who I want to continue working with and creating opportunities for making and problems to solve. Also, it’s been amazing to work with students during this period. I am so inspired by and feel for the young artists who are coming up in the world right now. What I’m finding really exciting is being able to say I hear you, I see you, please keep on going with this. So I would like to continue making work with totally fascinating, interesting, amazing people, and I would like to be seeing the development of the next generation of those people.

VI: Is there anything else you would like to add?

AT: I am hoping for more spaces for artists who are in school or other forms of siloed frameworks to find ways of reaching out and working in other disciplines since that adds to an artistic vision and statement. I have found with the class I’ve been teaching this past semester, a multimedia performance class, that some of the students are finding it to be a unique space to exist in. I hope that this is really some type of expansive turning point for artists who have been working beyond category to be seen as uniquely suited for the furthering of the form and for a wider audience to find themselves curious about this kind of work.

For more information on Ashley Tata and upcoming work, you can visit Ashley’s website here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Victoria Isotti.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.