We have of late enjoyed a number of plays about Chinese immigration to New Zealand, from Katlyn Wong’s Mui (2006) to Renee Liang’s Under the Same Moon (2015), Liang’s The Bone Feeder play (2011) and The Bone Feeder opera (2017) which does have a Māori-Chinese connection, albeit post mortem. However, Mei-Lin Te Puea Hansen’s The Mooncake and the Kumara is the first play I can recall that explores the Māori-Chinese cultural mix.

Set in the 1920s, it doesn’t purport to depict the origins of such cross-fertilisation. It captures a time when Māori were increasingly dispossessed of their lands and Chinese immigrants were subjected to appalling discrimination – not least (and I didn’t know this before) by the government, which made it very difficult for women to join their menfolk in the ‘new land.’ presumably to avoid new generations of New Zealand-born Chinese insinuating themselves into ‘Godzone.’

Elizabeth Whiting’s costume designs seem more pre than post World War One, but we’re in some unnamed rural outpost so I trust her judgment on that.

It is a staple of our immigration stories (and Māori country-to-city stories, for that matter) that the younger generation resists the repressive ‘old ways,’ and the restrictive rules surrounding love and marriage, let alone procreation ‘out of wedlock,’ have generated drama ever since the art form was invented.

In this respect, Mei-Lin Te Puea Hansen’s play, as directed by Katie Wolfe, tantalizes us by not making the inevitable too predictable. Then, when it does happen, an obstacle is thrown in the way that makes us care even more whether love will finally prevail. The burgeoning romance sits at the core of a much bigger story that compellingly compares and contrasts interpersonal and cultural relationships across generations, with often humorous insight.

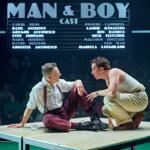

Unobtrusively lit by Paul Lim, John Verryt’s multi-levelled set, apparently supported by un-milled branches, allows for seamless transitions between the homes of Wae and her daughter Elsie; Choi and his son Yee; up a level to the landlord of both truncated families, Finlayson; and most aloft and removed, Leilan, whose specific relationship to the ‘present’ story is not disclosed for a while, so I won’t reveal it here.

Drew McMillan’s sound design is especially effective in bringing an ‘other worldly’ feel to Leilan’s scenes.

We are also made to wait and really want to know before we discover why Wae and Elsie are so disconnected from whanau, hapu and iwi, and what exactly happened to the husband/ father, Taki. The background to Choi and Yee’s circumstances are also gradually revealed, and there is more than meets the eye to Finlayson as well.

Despite Wae’s knee-jerk ‘because they’re different’ prejudice against the Chinese, their need to earn money to pay rent to Finlayson compels them to work for Choi, who distrusts them too, work ethic-wise. He insists everything is done “Chinese way!” Their gradual coming to know and understand each other brings effortless energy to the well-crafted narrative structure.

Jeremy Randerson (who also played the role in 2015) offers a surprisingly two-dimensional Finlayson, possibly because he is pre-judging the character rather than ‘being him’ him, flaws-and-all, and leaving us to do the judging. I objectively understand him (it’s all in the text) but I don’t believe in him enough to empathize – which would have more impact, politically.

Waimihi Hotere and Charles Chan are original cast members and their performances are rich in detail. Hotere’s Wae is entertainingly eloquent in her unspoken responses to what’s happening, and she’s a force to be reckoned with whenever she speaks up.

Chan’s Choi is deeply-felt and sometimes seems stylized (a nod to Chinese Opera conventions, perhaps?) which is entirely appropriate, given his attempts to adhere to tradition.

Leilan is clearly a sad figure who alleviates her disenfranchisement through fantasy, and Katlyn Wong is utterly compelling as she traverses a range of states of being. Her meta-theatrical agency as an observer, listener, and deliverer of letters and tea adds an enriching directorial touch.

As Yee, the young man wanting to embrace this new world and life while conscious of his duty to what he has left behind, Sam Wang is convincingly riddled with the complexities of his situation.

Elsie is the most inclined to move on into a new and unknown future with no-nonsense determination, and in a richly nuanced performance, Neenah Dekkers-Reihana embodies the role with wholehearted flair and energy. The evolving relationship between Elsie and Yee is a life-affirming counterpoint to the downward pressure on all their lives – which makes the aforementioned sudden turn of events all the more dramatic.

I confess I’m surprised, on arrival, to see Neenah’s name in the program, as I hadn’t noticed it when loading the production details a couple of weeks ago. Besides, hadn’t she been doing her solo show, This Is What It Looks Like, just last week at BATS? Only aafterward do I discover she stepped up to replace a flu-hit actress on Tuesday – two days before opening! The Hannah Playhouse bar is abuzz with the miracle of that achievement!

The Mooncake and the Kumara is an exceptional production on many levels.

THE MOONCAKE AND THE KŪMARA

by Mei-Lin Te Puea Hansen

Directed by Katie Wolfe

Produced by The Oryza Foundation for Asian Performing Arts and Betsy & Mana Productionsat Hannah Playhouse, Wellington

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by John Smythe.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.