Perhaps it’s an indicator of the feebleness of new writing after the pandemic that so many of the current highly hyped plays are 1990s and 2000s revivals — success in the past is, it is hoped, a guarantee of success today. Examples include Martin McDonagh’s The Pillowman and Mike Bartlett’s Cock in the West End, and Tom Stoppard’s The Invention of Love and Polly Stenham’s That Face Off-West End. Sarah Kane’s 4.48 Psychosis was recently revived at its original venue, the Royal Court, with its original director and cast. Now it’s the turn of Irish playwright Conor McPherson’s The Weir to return to the West End in a triumphant revival.

First staged in 1997 at the Royal Court’s studio space at the Ambassadors Theatre, where the Court was temporarily relocated while its Sloane Square base was being refurbished, The Weir was an instant hit. I saw it when it opened, and I remember a woman fainting during that performance, and I also saw it again when it transferred, with a starry cast, to the large Duke of York’s Theatre for another successful run. It was revived again in 2013 by the Donmar Warehouse, with Succession’s Brian Cox leading the ensemble, and this time the celebrity draw is Brendan Gleeson, making his West End debut at 70 and whose CV includes the film The Banshees of Inisherin and the television series State of the Union.

One stormy night, in a County Leitrim pub, three local men gather for a quiet drink in this isolated location. They are Brendan, the publican, Jack, a car mechanic and garage owner, and Jim, who does odd jobs. Soon their evening is energized by the arrival of Finbar, a local businessman, who brings with him Valerie, a 30-something single woman who has arrived from Dublin and is renting an old house nearby. As the drink starts to flow, the men take turns to tell ghost stories, with a typical mix of banter, boast and bravado. Then Valerie tells her own ghost story, which reveals both the reason for her leaving Dublin and shows much more emotional intelligence than theirs. It is also much more terribly personal than the men’s tales.

The men tell stories to impress and attract Valerie, and the ghostly nature of the tales evokes the rural traditions of Ireland, with its fairy forts and wild spirits, its graveyards and its impoverished communities. Although the Catholic church is mentioned, its presence is nowhere near as strong as that of these older folk beliefs. Equally ancient is this clash of male egos: if Finbar is the alpha male, loud and unsubtle and — unlike the others — much more of a material success, Jack, Brendan and Jim are always ready to take him down a peg. McPherson brilliantly orchestrates the melody of the storytelling — each instant being a non-naturalistic monologue — as well as the complex choreography of the drinking. Every successive story raises the emotional temperature of the evening until the day closes on a quietly redemptive note.

While Valerie outshines the male competition with the intensity of her contribution, the general tone of the play is a perfect balance between the mundane banality of a night in the pub and the strange possibilities offered by the workings of spirits and ghosts. Inside all is warm and convivial, outside the wind whispers intimations of another world. As the tales are recounted, all involved discuss the reality of these events in a wonderfully random and fractured way. Do spirits exist, or is there another more rational explanation for weird happenings? McPherson is not tempted to give an answer, but lets the tension between the supernatural and the everyday hang in the air like cigarette smoke.

Unlike the in-yer-face plays of the 1990s, The Weir explores a much more spiritual and humane sensibility, a marked contrast to the brash sex-drugs-and-violence plays of that era. Yet, at the same time, McPherson’s drama does share some features with those of his contemporaries: love of storytelling, interest in the pains of masculinity and in subjective states of mind. Although this piece doesn’t engage with either sexual violence or overt toxicity, it does include a story about a paedophile, which is written with an emotionally sincere sense of social awkwardness and a touch of open-mouth comedy. All of which is upended by the tragic quality of Valerie’s story, and Jack’s simple, and very personal, final tale of a lost love.

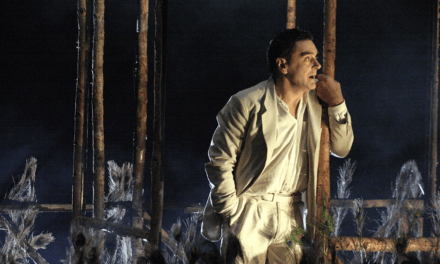

Directed, like The Brightening Air earlier this year, by the playwright, and perfectly designed by Rae Smith, The Weir is one of the most beguiling 105 minutes I’ve ever spent in the theatre. McPherson brings the curtain up with a few bars of Richard Strauss’s “Four Last Songs”, which prepares us for these stories of love and loss and lonely lives lived in isolation. In this rural setting Dublin is more distant than the moon, and human relationships are long-lived as each man remembers incidents from their life, and reminds the others of old grudges and failures. Because Valerie is not only a woman, but also an outsider, she brings a fresh eye to this situation. Which is both comic and profound.

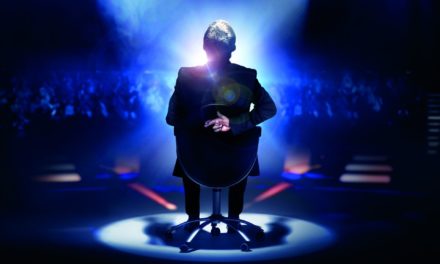

This haunting play depends entirely on the acting, most of which is beautifully well paced and completely convincing. Gleeson, a huge stage presence, expresses a mass of different feelings through his highly expressive craggy face. His body dominates the space of the bar, but it is his eyes, alert and flickering, that attract your attention. While Owen McDonnell’s Brendan hides his loneliness behind an efficient worldly manner, Sean McGinley’s Jim, who lives with his old and sickly mother, is awkward, taciturn then suddenly verbose. All struggle with their inner sense of failure. By contrast, Tom Vaughan Lawlor’s Finbar is able to literally jump for joy as he introduces Valerie, who he knows will attract and astonish the other men. His wider experience of life in the larger world beyond this rural backwater cannot, however, save him from being gauche and vulgar.

Kate Phillips plays Valerie with a soft touch that hides her feeling of being a newcomer. When she orders white wine, her normal Dublin drink, Brendan has to go into the main house to find an old bottle left over from some previous celebration, and when she needs the toilet he has to take her there because he’s never got around to building a ladies loo next to the pub room. When Phillips tells her story, the men become immobile, gripped and shocked by the awfulness of her experiences, and feeling the pain of her restrained but exceptionally moving tale. She’s also there at the end of the evening, sharing with Gleeson a brief moment of human connection. A great finishing touch to a production that is both haunting and brimming with emotional truth.

- The Weir is at the Harold Pinter Theatre until 6 December.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.