This year the stage threw up apostles of hope aplenty, whose quiet energy and presence allowed us to re-imagine our own lives in the sheer privacy afforded by a seat in a darkened auditorium. Here’s a baker’s dozen of those who’ve left an impression with their ephemeral one-night-only outings that still linger on.

Abir Abrar, Sounding Vanya

In this free-wheeling dismantling and restructuring of Uncle Vanya, Abrar plays almost every part, yet she is an entity with a narrative all of their own. She owns the play’s emotional highlights and whips up the intensity in spades, and even when she recedes to the sideline, she is a smoldering presence who adds much to the goings-on. It is a part that allows the consummate actor to blossom untrammeled.

Jyoti Dogra, Black Hole

Photo courtesy of thehindu.com

The sheer artistry of what Dogra effects on stage, accompanied with just a sheet, is just one facet of her performance in Black Hole, a play she’s single-handedly created. There is also the heartbreaking trajectory of a terminally ill woman and her daughter. Dogra starts off as anxious narrator, before settling into a more self-assuredly cerebral presence, taking the play’s engagement with science to a more transcendental plane.

Kaustav Sinha, Raamji Aayenge

Sinha’s anthropomorphic vanar Bhonpu is a stand-in for battle-worn Estragon from Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, of which Raamji Aayenge is an adaptation. He chips in an understated turn sans ostentation, with a consistency of quality never short on truth or intensity or humor. His Zen-like bearings add volumes to the play’s temporal shifts across ages, even as he crafts an ‘otherness’ that helps reveal the follies of mankind.

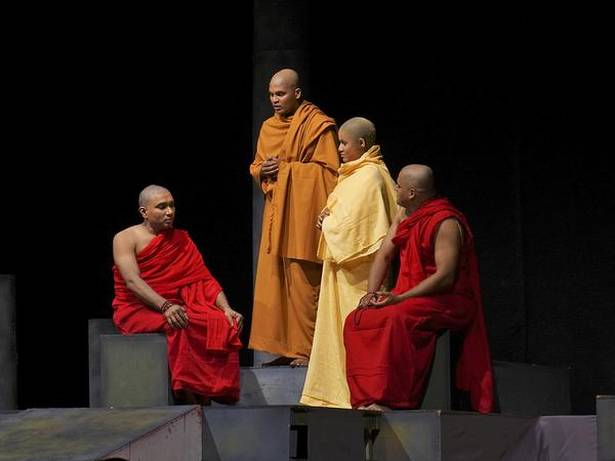

Keatan Jadhav, Avyahat

Photo courtesy of thehindu.com

By dint of characterization, Jadhav has the onerous task of bringing to life the Buddhist monk Upali, who sought to demystify the Buddha in Asoka’s time. It’s an author-backed role that the young actor does full justice to, handling the period-inflected dialectic text with considerable aplomb, and evoking to no small degree the fortitude and gravitas and formal manner of a radical visionary quite ahead of his time.

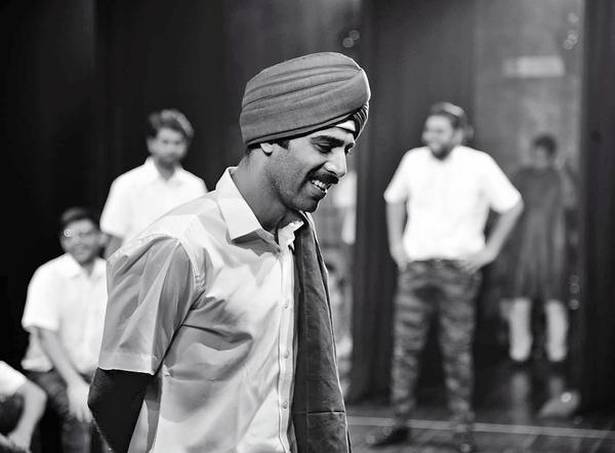

Himanshu Talreja, Gagan Damama Bajyo

Photo courtesy of thehindu.com

Supported by a chorus who collectively evoke the zeitgeist of the 1920s, Talreja as Bhagat Singh nonetheless appears to single-handedly bear the cross of his generation. His is a demeanor charged with both the naiveté of youth and the halo of an impending martyrdom that he recognizes as inevitable. Far from chest-thumping, Talreja’s intensely private portrayal stays with audiences long after the music dies down.

Manikandan, Pulijanmam

Enacting the Pulaya epic hero Kari Gurukkal in a retreading of a classic text, Manikandan breathes fire and fury into an elemental performance that extracts blood both psychologically and physically (he plays an ostensible master of ten martial arts). As a man who turns irrevocably into a tiger, the underrated actor channelizes both human and feral torment in a composite of anguish and unwitting actualization that is bone-chillingly evoked.

Parna Pethe, Bone of Contention in Cosmopolitan CHS

In a broad farce that plays off stereotypes to hilarious effect, Pethe brings a self-possessed poise and an introspective eye as the ubiquitous friendly neighborhood help, who does the rounds of many bickering households. In a part that’s not without its high jinks — Pethe even raps with alacrity — it is at her most sedate that her worldly-wise character omnisciently gives us a soft-eyed glimpse of real cosmopolitanism.

Pallavi Jadhao, Man Maana Square

In an ensemble piece that she’s devised with three other actors, Jadhao is all spirit and vim and laces her characters with a deliciously humorous edge good for many laughs. Her unabashed (and touching) portrayal of repressed feminine desire and angst finding some expression, rescues her parts from becoming easy caricatures, with her alternatively subaltern and bourgeois women acquiring fleshed-out inner workings that make them characters for the ages.

Puja Sarup, Sounding Vanya

Photo courtesy of thehindu.com

What Sarup gives this inventive retread of Anton Chekhov’s masterpiece is a bewitching and almost careless languor, switching between men and women of distant Russia without scarcely gendering the act of transference, watching over the play with her gaze and breathtakingly holding the drama even in her moments of utter stillness. It’s a performance that displays an effortlessness of craft that calls for very little of her trademark flamboyance.

Rachel D’Souza, Shikaar

Photo courtesy of thehindu.com

In a high-camp performance that calls into magical submission both the comedic and the cataclysmic, D’Souza is one of an intrepid breed of dyed-in-the-wool chudails. While she revels in the commune’s self-sufficiency of spirit and ‘wicked witchiness’, she essays a conflicted soul whose persuasions are decidedly off-beat. It is textbook humor performed with heart, and in the process, broad strokes acquire a disarming subtlety.

Ronita Mookerji, I am not here

Photo courtesy of thehindu.com

In a tight two-hander, Mookerji is a devil-may-care presence seemingly untouched by the piece’s feminist angst but mindful of its repercussions on her own body. As she physically negotiates a curve from prescriptive Bharat Natyam to her own free form style, she steadily throws up charged metaphors that remind us of pain and resilience equally and allows the play to reach its moments of insight and revelation.

Tavish Bhattacharyya, A Few Good Men

In the eye of the storm in a military tribunal, Bhattacharyya’s Harold Dawson commands begrudging attention as a man who acts in collusion with higher-ups but will not acquiesce to becoming a fall guy. It’s a measured turn that straddles both dissent and loyalty, and Bhattacharyya’s stoicism and composure go a long way in a play that owes more to its moments of stillness than to occasional scenery-chewing.

Photo courtesy of thehindu.com

Vijay Patidar, Eidgah Ke Jinnat

Photo courtesy of thehindu.com

As his right-wing Hindu soldier posted in strife-ridden Kashmir teeters on the edge of overwrought delusion, Patidar gives us a heart-breaking glimpse of his battered soul. In a role that is part apologia and part indictment of the veritable heart of darkness that has engulfed its converts, Patidar deftly walks a precarious tightrope between caricature and believability, between judgment and conciliation, and never once loses his balance at all.

This article was originally posted at thehindu.com on January 3rd, 2020 and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vikram Phukan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.