Eugene Ionesco’s 1952 play The Chairs belongs to the moment of post-second world war European theatre history to which the Hungarian-British arts journalist Martin Esslin gave the catchy label of ‘the theatre of the absurd’. Although the Romanian-French playwright rejected this label, much of his work, as well as that of his contemporary, the Irish-French author Samuel Beckett, does reflect the spirit of the time Esslin understood as reflective of the absurdity and meaninglessness of the human condition vis-a-vis the horrors of war.

At the centre of The Chairs is a couple of nonagenerians, a janitor and his wife, who are preparing a ceremonial public address at which the Old Man will deliver his message about the meaning of life via a specially appointed Orator. The incoming esteemed guests are all invisible to the audience and only represented on the stage by their corresponding seating arrangements. As the audience await the arrival of the Orator, the Emperor is the last important invisible guest to arrive, and the Orator’s own arrival, intended to be performed by a third actor, is a dramatic and semantic anti-climax as, despite his visual manifestation, he is revealed to be deaf and technically inaudible.

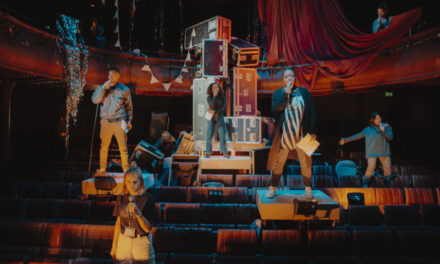

It is hard not to read this new production of The Chairs at London’s Almeida Theatre as an exploration of the absurdity of our own post-covid, post-Brexit, war-crisis time in Europe. Palestinian-Italian director Omar Elerian delivers a strikingly inspired production on a number of levels. It seems Incredible no one has yet had the idea to cast the star couple of British physical theatre Greek-born Kathryn Hunter and Italian-born Marcello Magni in this play before – a powerful concept in itself which Elerian builds into the foundations of his playful, poetic and supremely charming rendition of the absurdist tragic farce. The cast are also joined by Toby Sedgwick who completes the Lecoq-trained outfit to play the Orator – or ‘the Speaker’ as he is called in Elerian’s translation of the play. Though this yields a useful gag to briefly evoke the British Houses of Parliament, it is worth noting that Elerian’s translation project – also incidentally rich with rhyming flair – is more philosophical than political in its overarching tone.

PC: press photo.

Elerian latches onto the intrinsic metatheatrical dimension of Ionesco’s play – the way in which the audience’s imaginative investment in a live performance is assumed as capable of conjuring up meaning in the very places that lack the visible or the audible material content. Where the meaning-making agency is thus delegated to the audience, the actors are freed up to shine in their ingenious playfulness, although this particular creative team is never at risk of complacency. Taking Ionesco’s dramaturgical cue, Elerian’s translation features clever adjustments and judicious additions that keep reminding us we are in the theatre – and this in itself is a source of delight and fervour for all of us who missed the experience during the pandemic.

Though I have provided a nearly complete summary of Ionesco’s play above, this contains no spoilers, only necessary pre-knowledge to fully appreciate the nature of Elerian’s authorial interventions which achieve a new sense of suspense.

Productions of Ionesco’s plays in the UK have been few and far between, and this relative absence is partly explained in this production’s programme note by Katherine Mandelsohn as being linked to British theatre critic Kenneth Tynan’s dismissal of Ionesco and the theatre of the absurd as a fad of an inferior value to the British kitchen sink drama of the same period. Although in the more recent decades British theatre has generated an impressive diversity of stage language, at times spearheaded also by the likes of Hunter and Magni with Complicite or at the Young Vic and elsewhere, and by Elerian at the Bush, this joyful celebration of the unique power of theatre to enlighten and elevate, in the light of the newly imposed cultural insularity of Britain also feels like a bittersweet and deeply moving adieu.

I hope it storms the Oliviers.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Duška Radosavljević.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.