Kasia Lech (KL): How could we introduce Klątwa [The Curse] and its context to someone for whom the play, Polish theatre, and the Polish socio-political context are rather unknown?

Agata Łuksza (AŁ): Undoubtedly Klątwa, directed by Olivier Frljić, caused in Poland the greatest theatrical scandal of 2017. It premiered at the Powszechny Theatre in Warsaw, a city-subsidized institution led by Paweł Łysak and Paweł Sztarbowski who coined their theatre “theatre which interferes.” So far, all of Frljić’s attempts to cooperate with Polish theatres have resulted in nationwide discussions about the borders of theatre art. Klątwa really struck a chord by openly and unapologetically questioning the very strong political position of the Catholic Church in Poland. Not only did Frljić touch on an “untouchable” subject, but he also used religious symbols and icons against the grain of the dominant discourse and hence was accused of blasphemy. For instance, in one of the scenes wooden crosses change into weapons, in another a large cross is attacked and overturned, and in another, one of the actresses performs fellatio on a figure of the “Polish Pope,” John Paul II. This last scene instantly became one of the most talked-about moments in the history of Polish theatre and put the actress Julia Wyszyńska at direct risk, as after the premiere she began receiving numerous hate letters. While many theatre critics declared Klątwa to be the best theatre play of recent years and argued for its social and artistic value, the square where the Powszechny Theatre stands became a place of daily protests organised by radical right and Catholic groups attempting to ban further performances. The prosecutor’s office has initiated a criminal investigation into an alleged offence of religious feelings.

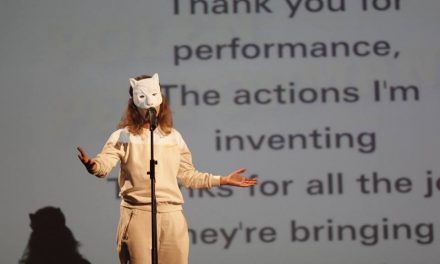

![“Klątwa” [“The Curse”], adapted from Stanisław Wyspiański’s play, dir. by Olivier Frljić, Teatr Powszechny in Warsaw, Jacek Beler, Photograph by Magda Hueckel.](https://thetheatretimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Klatwa-2-1024x683.jpg)

Klątwa [The Curse], adapted from Stanisław Wyspiański’s play, dir. by Olivier Frljić, Teatr Powszechny in Warsaw, Jacek Beler, Photograph by Magda Hueckel.

AŁ: Klątwa is a very dynamic show, which–like a revue–consists of diverse tableaux and monologues stirring up different emotions, such as laughter, sadness, anger, embarrassment. There are many moments which linger long after the show is done, images that cannot be unseen and words which cannot be unheard. While the “fellatio scene” became the most infamous one, I was particularly touched by the scene in which the actors, dressed in black cassocks, use wooden crosses to build guns, subsequently pointed at the audience. The instant change of the religious symbol of transcendent love and ultimate sacrifice into a tool of violence, suffering, and death was deeply hurting, uncomfortable, and disenchanting. Especially given that it was followed by disturbing confessions of victims sexually abused in their childhood by Catholic priests.

KL: This was another sensitive issue that Klątwa raised and that I thought was somehow missing from the public discussion about the production. Undoubtedly the “horror” of the “fellatio scene” took center stage as “distorting the image of the Catholic Church.” In this sense, I thought it was very powerful to have the crosses at the start crooked. I read it as Frljić clearly highlighting that the Catholic Church and its ideals are distorted before the production starts. Nevertheless, emotions overtook the public discussion. And perhaps this was the biggest test that Klątwa was setting for its spectators and Poland: whether we are ready to discuss the Catholic Church.

AŁ: One may argue that because of its uncompromising character Klątwa in fact did not initiate any public discussion about the role of the Catholic Church in Poland, but rather caused an unnecessary conflict in a society already deeply divided. The violence executed by the Catholic Church–either physical or symbolical–could not become the subject of public debate because of the radical means used by Frljić which from the very beginning overshadowed any other issues raised by Klątwa. However, I would argue that this–obviously–expected outcome of Klątwa confirms the social diagnosis embedded in the performance: no dialogue is possible in Poland between radical Catholics and nationalists, on the one side, and people who question the power and hypocrisy of the Catholic Church, on the other side. The fact that at the moment there is a criminal investigation concerning Klątwa makes it clear that the idea of a “dialogue” is a mirage. How can one aim at consensus, if one is forbidden to talk? Therefore, Klątwa should be regarded, in my opinion, as a desperate voice of protest against the way the Catholic Church in Poland influences the political, legal, and educational systems which frame the everyday lives of all Polish people who supposedly live in a secular country.

![“Klątwa” [“The Curse”], adapted from Stanisław Wyspiański’s play, dir. by Olivier Frljić, Teatr Powszechny in Warsaw, Photograph by Magda Hueckel.](https://thetheatretimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Klatwa-3-1024x668.jpg)

Klątwa [The Curse], adapted from Stanisław Wyspiański’s play, dir. by Olivier Frljić, Teatr Powszechny in Warsaw, Photograph by Magda Hueckel.

AŁ: Wyspiański’s drama Klątwa hovers over Frljić’s work in an unexpected way. Parts of Wyspiański’s text are interwoven into the performance, but Klątwa is not a performance with a traditional plot and stable characters. Truth be told, most of the time actors play themselves or, rather, some versions of themselves. Despite the fact that one could hardly call Frljić’s performance the staging of the drama Klątwa, Wyspiański’s diagnosis of Polish religiousness was as critical as Frljić’s. However, I am not sure whether Frljić’s adversaries are aware of that–Wyspiański has been canonized as a Polish bard along with the greatest Polish romantic poets, Mickiewicz and Słowacki, and thus the disruptive, deconstructive, and critical aspects of his work have been largely forgotten or erased from collective memory. Therefore, it might be a good place to recall that in Wyspiański’s Klątwa a local priest fathers two children with his housekeeper to everybody’s knowledge, the mother eventually burns these children to “purify” their souls and in turn goes mad and is stoned to death by townsfolk. Is it really less shocking and disturbing than Frljić’s work?

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Agata Łuksza.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.