Gia Forakis accepted our request to glimpse into her vision and creative processes at her Brooklyn Parkway Place Studio. It is there that she conducts workshops, rehearsals and creates events inspired by a technique she has developed called One-Thought-One-Action (OTOA). Even on a rainy day, the studio is bright, impeccably organized, and serene. We begin chatting in the administrative section of the studio.

GIA FORAKIS: So, this is the visual art/creation area–I am a Theatre Artist, but part of my theatre aesthetic stems from also being a painter. I really compose the mise en scène. I do write my own works for the stage, but when I direct the works of others, I draw things out on paper because it’s not familiar to me and it helps me to envision it. As a visual artist this affords me another avenue of expression in my creative practice, which is all built upon One-Thought-One-Action (OTOA).

I began developing OTOA in 2003, while I was still in grad school at Yale School of Drama, in the directing program. Originally, it was a way to communicate my directorial aesthetic. Eventually, it evolved into a performance technique, which I have used as a stage director, and which I have been teaching to performing artists, locally, nationally, and internationally, for over 10 years.

Over the years, OTOA has expanded into a second application, which I call OTOA Creative Life Practice–or C.L.P. The emphasis of CLP is that you don’t have to be an artist to have a creative life practice. We now conduct workshops based on both these curriculums–OTOA Performance Technique & Training and OTOA Creative Life Practice–here in this space.

We then curiously take the opportunity to get inside the mind of a real purpose driven artist to discuss Gia’s projects past, present, and soon to be.

Gia takes us into the larger space of her studio where we sit down to further discuss her process for actualizing OTOA and what her Creative Life Practice really means.

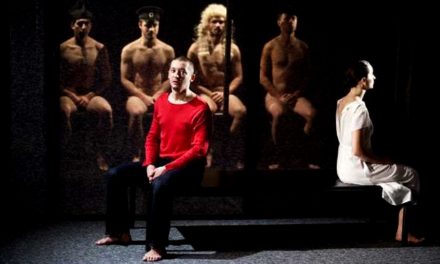

Fatelessness: A One Man Show based on the novel by Imre Kertész. Co-Created & Adapted for the stage by Adam Boncz and Gia Forakis. Directed by Gia Forakis. Performed by Adam Boncz. Co-Produced by GF&CO & Scene House Co-Production. HERE Art Center, NYC. Photographs & Set Design: by Lauren Mills.

Photo Credit: Matteo Cali

DAVID VERNON: Gia, firstly, I want to talk to you more specifically about your solo performances in Lower Manhattan as a performance artist. Tell us a bit more about your history in that area.

GIA FORAKIS: I began my relationship with the theatre at the age of 7, performing in a production by Meredith Monk at the Guggenheim Museum. The production was called Juice and that introduction began my lifelong relationship with the stage. I refer to myself now as a theatre artist but I began as an actor. I got my BFA at the NYU Tisch acting conservatory, which is now known as Tisch Graduate Acting, where I received a more formal and traditional acting training. Soon after that, I went into a very unconventional pursuit of theatre that incorporated movement, dance, multimedia, and creating my own works for the stage. I created that sort of work for 17 years. Some of it was solo work, but not all of it. I was sometimes referred to as a performance artist, but I thought of myself an experimental theatre artist because I referenced both the classic traditions of the theatre with the more fringe based exploration of dance, multimedia, and the influences of the downtown art scene that was going on back then in the Off-Off Broadway arena.

DAVID VERNON: How would you say that scene has evolved and changed since that period of time?

GIA FORAKIS: Well, that’s a big and important question. It’s a really important question for young people coming up right now because when we were coming up in New York in the 80s and the 90s, there was the strongly supported possibility that you could make a living as an artist in this city. You might not ever become rich, but you could make due and make art. I could work three-four days a week and earn enough to cover my expenses and then have the remaining 3-4 days to work exclusively on my art. Back then, rents were cheaper and there was a lot more support and the city was much more of an Artist City. Now, the city has become much more of a Wall Street economy.

And this has changed the way we make theatre with a more monetized motivation for both stage and visual art, too. When I was coming up, there was much more room and encouragement for process, development, and experimentation. Creative freedom is the challenge now and how to work within this changing system, which has led me to where I am now.

DAVID VERNON: Tell us about your aesthetics as a director.

GIA FORAKIS: I’ll answer that question in two parts. My aesthetic as a stage director is built first on a desire to create an experience that captures the poetic nature of the human condition. It’s a desire to connect with something larger than our sense of self, something sacred. And that’s what I see as the beauty of the theatre.

In terms of the expression of that desire, my process is to bring to life a very visual, theatrical, and specific life on stage that illuminates increments of thought as components of physical action, which is how I articulate the methodology of One-Thought-One-Action.

The beauty of OTOA is that if you want to, you can use it almost like the cinematic process of editing film where one can compose one frame of action at a time. It’s how the text supports the physical actions on stage so that even if you could turn off the sound of the actors, the viewer would still get the story being told through the visual embodiment of thought as physical action.

Fatelessness: A One Man Show based on the novel by Imre Kertész. Co-Created & Adapted for the stage by Adam Boncz and Gia Forakis. Directed by Gia Forakis. Performed by Adam Boncz. Co-Produced by GF&CO & Scene House Co-Production. HERE Art Center, NYC. Photographs & Set Design: by Lauren Mills.

DAVID VERNON: How would you best define your ritual for creativity and how is it essential to your creation (because all of us artists have some sort of ritual)?

GIA FORAKIS: In relation to the question, my answer has changed over the course of many decades–what I perceive as ritual and how I think about it in performance, and then how I now see it as practice. I’ve come to the place where I feel that as artists, to be holistic as creatives, we need to be a part of our daily creative practice, meaning, one has to live their ritual. Your practice–no matter what medium it is through which you express yourself–does not only take place in the studio. It can’t just all of a sudden happen. Our lives have to be our creative practice, and that’s the practice. To begin your day in the sacred relationship with your “whatever it is,” and then to walk through your life as that artist–and that is all a part of actualizing your practice. Even your “day job” has to be seen as serving that purpose. The day job serves the bigger picture and if you don’t have a sacred ritual that connects you and it that carries you through the day with that awareness in relation to your artistic being, then your life is split up and compartmentalized, and that thing that is your best part isn’t being enriched.

DAVID VERNON: I think especially as artists we don’t actually tap into our full potential until we’re actually willing to embrace and step into that. It’s then that we can truly co-create with one another.

GIA FORAKIS: Even if you’re not an artist you can still benefit from a creative life practice. Ultimately what we’re talking about in ritual and sacred relationship is what it is that’s true to us– living connected to something that is bigger than us and that we’re meeting the world in that way all day.

Song From The Uproar: The Lives & Deaths Of Isabelle Eberhart–Gia Forakis was one of the four original collaborators on the premiere production of this multi-media opera, composed by Missy Mazzoli, produced by Beth Morrison Productions and directed & choreographed by Gia Forakis. SFTU, premiered at The Kitchen in NYC, and was remounted at LA Opera’s RED CAT Theatre. Photo Credit: James Matthew Daniel

DAVID VERNON: Let’s next talk about Gia Forakis the Master Teacher of One-Thought-One-Action.

GIA FORAKIS: This beautiful thing has happened when I came to recognize my need to live holistically as an artist from the minute I wake up, because, originally, OTOA began primarily as a performance technique. But soon it became clear that I had to practice what I was preaching–not just in the rehearsal room or the classroom–I had to walk the talk all of the time, and live it in order to really teach it. And that’s where this holistic application of OTOA as Creative Life Practice stemmed from.

Photo Credit: Matteo Cali

DAVID VERNON: What do you find rewarding through teaching and coaching?

GIA FORAKIS: Whether I am teaching, directing, creating, or coaching OTOA, what is so rewarding is that it “is the thing itself,” so as I teach it, or coach it, or direct it, I am also practicing it. At a certain point in life, one begins to see the patterns of their life. You have to live long enough to recognize “Oh! I’m here again” or “Oh! That thing that I did decades ago was so that I could have this moment right now!” That’s a lot about why I find teaching so rewarding. It puts into context and applies all the benefits of my experiences–good, bad, or otherwise–into a positive application. I think that a part of being a mature artist is that I get to give back.

DAVID VERNON: I’m wondering how much more learning is there still for you as a teacher.

GIA FORAKIS: I’m still learning. The process of learning and teaching is on the spectrum of the whole.

DAVID VERNON: What’s next?

GIA FORAKIS: Next is March 24th GF&CO, which is my not-for-profit company, is hosting an Art Salon. We founded the company doing salons that were theatre-based. But, with Art Salons, we select 2-4 artists from a variety of mediums to present their work in a free, intimate, social environment with light refreshments and offer a way for artists across multiple platforms to cross-pollinate and interconnect. Then, in April & June we have a lot of OTOA workshops going on.

Plus, I’m developing my original project for the stage with GF&CO’s Associate Artistic Director, Darya Gauthier, called LOVE IN SPACE-TIME, which is not only written as an OTOA-based performance project, but it also brings my past as a performance artist, writing and creating original, multimedia projects for the stage, together with my present as an OTOA stage director. As the title suggests, it is an exploration in space-time, also known as the 4th dimension, or the time continuum. The script is a non-linear, experimental narrative that aims to create an experience of space-time–scenes overlap and repeat, and are layered on top of each other. Time and space are fluid. The story itself is a woman’s journey though the love and loss of a father, and the love and loss of a lover–suggesting that it’s during experiences of love and grief that a doorway into the 4th dimension opens up for us if we care to walk through…

Song From The Uproar: The Lives & Deaths Of Isabelle Eberhart–Gia Forakis was one of the four original collaborators on the premiere production of this multi-media opera, composed by Missy Mazzoli, produced by Beth Morrison Productions and directed & choreographed by Gia Forakis. SFTU, premiered at The Kitchen in NYC, and was remounted at LA Opera’s RED CAT Theatre. Photo Credit: James Matthew Daniel

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by David Vernon.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.