If modernity is a stage, the artwork is its main prop. And in a culminating planetary crisis, voiced in anti-humanitarian grammar, the spectacle’s fourth wall has long since melted into air, writes Frida Sandström, on the 58th Venice Biennale.

Without barricades, life is flooded by what Zygmunt Bauman calls ’ liquidizing powers’. Revolutionaries must swim, while technologies of the reigning institutions soak the social fabric: besides the governance from behind facades, the panopticon is consumed as a commodity. Today’s spectators exhibit themselves as others. The same goes for contemporary art, whose distributing techniques are configured as a post-Artaudian theatre of cruelty. Instead of being distributed, the sensible is disrupted. As a consequence, what inside the gallery seems to be the ruin of a torn down curtain or stage, is, in fact, a porous but steady grip on the material circumstances of life as a performance. Enacting the tools for survival, institutional rhizomes disable any attempt to unpack what Achille Mbembe calls the ”neuroeconomic subject”. And it certainly is the ”human- thing”, the ”human-machine”, the ”human- code” – the ”human-in-flux” that is at stake at the oldest halting-place of contemporary art production, this year materialized as a 200-meter queue to the French pavilion in Giardini, Venice.

Two hours later, Laure Prouvost’s Deep Sea Blue Surrounding You (2019) connects the floating signification of relations into the fabrication of glass: a mass that is only transparent when solidified. Surfing on what mainly looks like a big blurry screen of an old LCD-device, but that seems to be referring to the surface of an ocean, spectators join the staging of the sublime ending of the planet. Directing this drama with their individualized affective responses, they recognize themselves in every corner of the clear blue-green space. Someone shouts with nostalgic glittery eyes: “there’s the phone I had ten years ago,” while I am myself reminded of the times of iPod music. It’s clear that this piece is not about what is below the surface, but rather about who glances down on it, finding themselves looking back.

Deep Sea Blue Surrounding You (2019) by Laure Prouvost. Photo by Francesco Galli. Courtesy the artist, La Biennale di Venezia.

The props of tech that Prouvost has distributed over the space—some found objects, other fabricated by colored glass—reflect back to the consumers’ memories, historical purchases that made us into what we are today. Relying on self-recognition as the main drive for care, the installation provides no attempt to complicate the line of consequences between presence, action, and trace. Instead, spectators are invited to enter the pavilion from down a dug-out passage below the modernist architecture, to soon walk onto the surface of the mimicked water, and later enter a cave-like, dried out bottom of the ocean. In there, they join a cinemato-nomadic journey from a Parisian suburb, over the limestones of the Marseillan coast, past the Mediterranean sea and finally occupying the national pavilion in floating Venice.

In the contradictory joyful flux of forced migration, the question arises: who is occupying and who is being occupied? Avoiding any such standpoint, or even any tendency to self-reflect, the pavilion is saturated by a romantic foam of the disappearing Other—enchanting the well-dressed crowd of plane-carried visitors. And yet, the anthem of these aesthetics, just as with the social media companies, sings that ‘all life matters’. Plankton, fish and even electrons. Human life goes without saying. Or…

The same inconvenience applies to the Nordic pavilion, where the backlash of the anthropocene is camouflaged by natural science’s oldest strategy: the discursive construction of bare life. From inside a eugenic market of over-analyzed living matter, soft technology voices the very same narratives that since long have turned lives into numbers. Strangely enough, the dangerously positivist recourse to biology is now saluted by the radicals. It is clear that surplus life here only materializes as an economic value, never returned to the body’s muscular transformation of oxygen to carbon dioxide, or the other way around (if it’s a plant).

On the opposite side of Prouvost lies the German pavilion, inaugurated by Hitler and ever since, a target for confrontation with the art history of nationalist distribution of artifacts. After Hans Haake’s 1993 Germania, when the artist demolished the marble floor—and the fashionable techno-fascism of Anne Imhof, the heavily worn concrete structure is confronted by Natascha Sadr Haghighian’s (aka Süder Happelmann’s) sound piece tribute to whistle (2019) as part of her installation Ankerzentrum (surviving in the ruinous ruin) (2018). This installation refuses to stage anything other than a general lack of public action. For the most part, all of the works in the park indirectly refer to such a need.

Tribute To Whistle (2019) by Natascha Süder Happelmann. Photo by Jasper Kettner.

As is often the case, Sadr Haghighian avoids references to direct narratives, and instead repositions the infrastructure of public life into the gallery space, simply reminding the visitor to take it from there. Building barricades, mobilizing as a group. Yes, this might actually be the only pavilion where spectators look into each other’s eyes. A strength of Sadr Haghighian is that she never mimics the square: she rather re-composes it into a toolbox. And with infrastructure, I really mean literal support structures without polish: metal pipes and plastic strips, banners, and dirt. This time the construction carries 48 speakers that a-synchronically emit the sound of whispering pipes, from time to time blending together into a multitude of non-human screams. In contrast to the previously mentioned mirror-scape of the ocean’s surface, Sadr Haghighian demands recognition of the overlooked other. But that’s the only thing she does.

The gallery space is split in half by what seems like the concrete wall of a riverbank, strangely similar to Germany-based Neda Saeedi’s piece in the Luleå biennale last year. But instead of referring to salt extraction and forced migration, the pavilion space is left vacant with only a few sips of the same solidified water as in Prouvost’s installation—in plastic this time. The fake ponds are accompanied by poorly mimicked rocks, somewhat confusing the otherwise clear sound spectrum behind the bank. From time to time the lightweight rocks are used as anonymizing hideouts for the artist and her spokesperson, covering their heads with the undefinable grey mass, as enacted in the artist’s online videos.

Ankerzentrum, exhibition view. Natascha Süder Happelmann (2019). Photo by Jasper Kettner.

Speaking of mimicking, a Joycean theatre is ever-present in this year’s biennale. One example is Russia’s “Lc. 15: 11-32”, narrating the history of Rembrandt’s The Return of the Prodigal Son (1669)—a piece that the curatorial body of the State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg exhibits as a permanent highlight. The price-winning Lithuanian opera Sun & Sea (Marina) (2019) by Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė, and Lina Lapelytė adopts the method of voluntary performance while blending paid performers with consumers of participation. Different from the French ocean’s surface, the fourth wall in this pavilion is reconstructed as a five-meter height distance—for those who don’t choose to part-take, that is—to a seemingly never-ending beach.

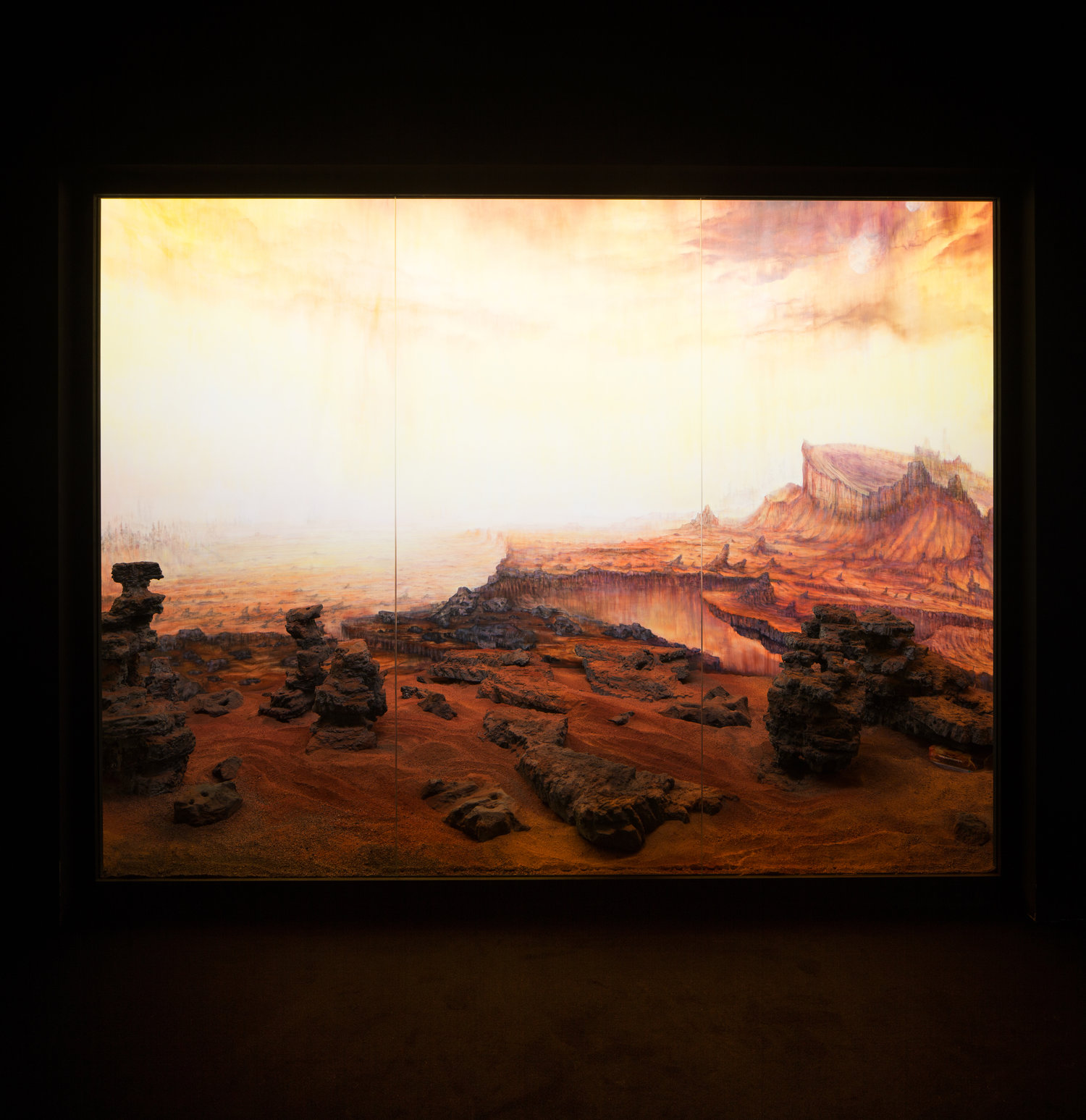

In the main exhibition of Giardini, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster and Joi Bittle’s dioramic installation Cosmorama (2019) counteracts the quantum physics-inspired flux of differentiated positions: listeners, receivers, actors. Already emancipated, the ethics of spectatorship is rebooted by an inverted verfremdung, not only awakening individual self-reflection—but also the structural grammar of performance as such. While Sun & Sea (Marina) is a lullaby to visitors who never experienced dried-out water, Cosmorama narrates the bitter taste of attempted travels to neighboring planets, like colonized lands were once was imitated in Western museums.

Sun & Sea (Marina) (2019) by Rugile Barzdziukaite, Vaiva Grainyte and Lina Lapelyte. Photo by Andrej Vasilenko.

Installation view of Cosmorama (2019) by Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster and Joi Bittle. Photo by Francesco Galli. Courtesy of the artists and La Biennale di Venezia.

Also in the Giardini, Halil Altindere’s Space Refugee (2016) perfectly inverts the narrative of space as a resource for great powers only. The collaged story-telling of Syrian astronaut Muhammed Ahmed Faris reflects on whether we need a new Black Atlantis—in space. Different from how Marshall McLuhan once interpreted cold, distanced media before the internet, these post-digital theatrical stagings remind us that sustainability on earth is only granted to those whose lives aren’t already contested on it. Altindere’s contribution thus reflects back to the biennale’s title ”May You Live in Interesting Times”—simply asking the reader to fuck off.

In the Polish pavilion, Roman Stańczak’s Flight (2019) shows a full-scale private jet plane that has been decomposed and inverted, then put together again, bluntly corrupting the world of mobile logistics for the wealthy. Without surfacing camouflage, the technological anatomy is clearly out of date. In the vacation of privilege, puppets from the same narrative pop up behind grills in the Belgian pavilion. In there, the theatre of colonial subjects gazes back onto the spectators, who, just like in the Nordic or the French pavilion are encouraged to ignore the fact that what they see is biographical: the biennale visitor is the referent of the numb puppet. From the weak underscore of such a contemporary absurdity, the exhibition in Arsenale ends with Christoph Büchel’s Barca Nostra (2019). Translated from Italian, the title “Our boat” refers to a shipwreck that once cost a hundred migrants’ their lives.

Space Refugee (2016) by Halil Altindere. Installation view, Giardini. Photo by Francesco Galli. Image courtsey: the artist and La Biennale di Venezia.

Flight (2019) by Roman Stańczak. Installation view. Photo by Francesco Galli. Photo by Francesco Galli. Courtesy the artist, La Biennale di Venezia.

Designated as a found object to signify whatever the artist desires, the vehicle is installed by the old quay without any reference to the “us” that the pronoun “our” draws from. Here, the vacant puppet-subject is exchanged for ice-cream and prosecco drinking visitors, unconsciously embodying the artist’s presence as absent, objective conceptualizer of life itself. In response, Shilpa Gupta’s sharp metal gate swings incessantly, like tortuous hits slowly crushing the chalky wall of Giardini. In Arsenale, the artist’s sound installation For, In Your Tongue I Cannot Fit (2017-18) voice poems of a hundred jailed poets from over the world over and the last decades are monitored against censorship.

Untitled (2009) by Shilpa Gupta. Photo by Francesco Galli. Courtesy the artist, La Biennale di Venezia.

For, In Your Tongue I Cannot Fit (2017-2018) by Shilpa Gupta. Photo by Francesco Galli. Courtesy the artist, La Biennale di Venezia.

In between the battle over tools to rebuild and recompose the ruins of the fourth walls, come montages of mass media. Both Arthur Jafa’s White Album (2018) and Kahlil Joseph’s BLCKNWS (2018 – ) point out the socio-choreographic imagery of public recognition, of the reproduction of normative lives and the maintenance work carried forth by the ignored, silenced and violated. The Venice biennale is still white as Hitler’s marble, yet the awakened recognition of colonial and capitalist history is barely connected to the eco-liberal crisis at large. In the Ghanaian pavilion, though, Selasi Awusi Sosu’s Glass Factory II (2019) thoroughly voices the hyper-productivity of an alienated workforce in glass production, sadly resonating with Prouvost’s reference to Italian Murano glass. Yet, the glasses that I sip my free prosecco from while cruising between the national pavilions’ reception parties are most certainly not produced locally.

Installation view of BLKNWS (2018 – ongoing) by Kahlil Joseph, in Giardini. Courtesy of the artist and La Biennale di Venezia.

Glass Factory II (2019) by Selasi Awusi Sosu. Installation view of Ghana Freedom. Photo by Italo Rondinella. Courtesy of the artist, La Biennale di Venezia.

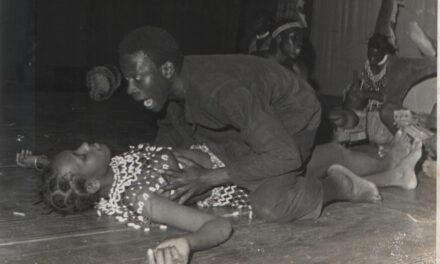

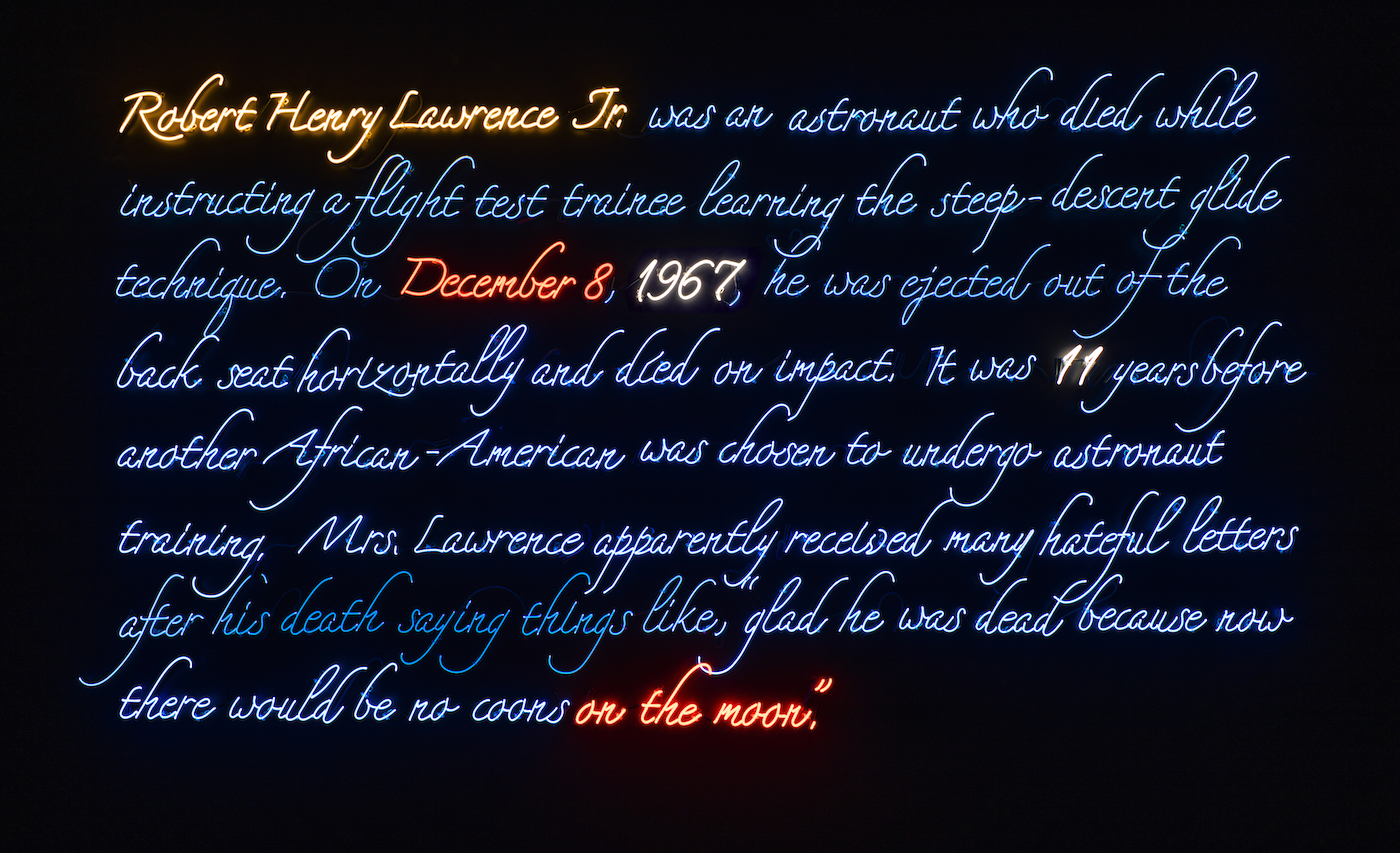

Perhaps blunt fiction is the only way to go. Just like Octavia Butler and other longstanding black female carriers of sci-fi, the genre is ever returning in Venice. And different from the biologically sublime shielding of the spectator-humans from any recognition of their own role in the consumption of these narratives—the sci-fi section includes the human consciousness as an essential tool for both communicating and digesting its burning history. This is especially present in Larissa Sansour’s Heirloom in the Danish pavilion, where the Cixousian relationship between mother and daughter is intertwined with collective memories of migration, echoing the uneasily carried scars of extractive violation. Similar to how the Cairo surrealists in the 40’s called the state of things ‘subjective realism’, Tavares Strachan’s Robert Henry Lawrence Jr (2018) reminds us of the surreal fact that black lives were sacrificed for white space travels.

In Vitro (2019) by Larissa Sansour and Søren Lind. Film still. Image courtesy of the artists.

Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. (2018) by Tavares Strachan. Photo by Brian Forrest, Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

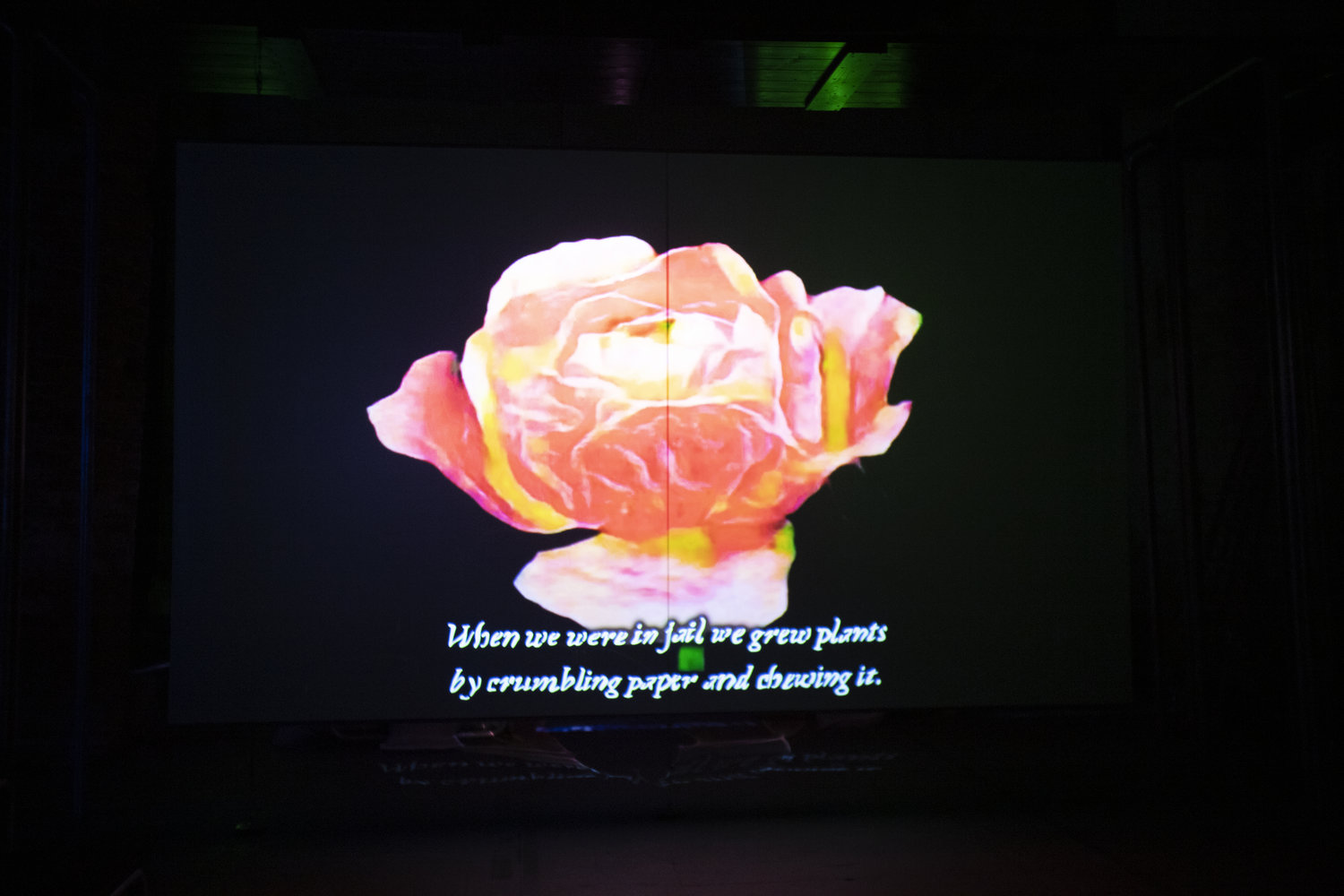

In Tamás Waliczky’s exhibition Imaginary Cameras in the Hungarian pavilion, the reason for the conflict between mother and daughter is clarified by the fact that everyone needs to carry these stories—as opposed to Büchel’s blunt co-opting of their most dehumanizing container. Giving body to such otherwise invisible apparatuses of control—enacted also inside the curatorial scope—Waliczky has reconstructed the social, lense-carried authority of modern history, with references from Eadweard Muybridge’s first ethnifying measurement of movement to today’s personalized panopticons. Direct measurement through algorithms is else quite absent this year, exchanged by mere images of such matter— alongside the self-care eugenics that Hito Steyerl clearly underscores in her short but sharp piece This is the Future (2019). Freshly intertwining contemporary positivist beliefs in quantum physics with neoliberal self-care spiritualism, Steyerl makes clear that even though the future is already out of stock, it belongs to no-one.

Imaginary Cameras, exhibition view. Photo by Francesco Galli. Image courtsey: La Biennale di Venezia.

This is the Future (2019) by Hito Steyerl. Photo by Italo Rondinella. Image courtsey: the artist and La Biennale di Venezia.

Another counter-action is found in both the Swiss and the Brazilian pavilion, where dance occupies the stage instead of letting it melt into artificial, participatory foam. The dancers’ movements in multitudes mark a clear response to refused proximity to neighboring lives in the else individualized understanding of the social in this year’s biennale. Such choreography also brings the thoughts to the Venezuelan pavilion. In the middle of Giardini, it materializes the vacuum of disaster that both Germany and France reach for, by simply being soaked in it. Different from the two European pavilion’s minimalist tools (water, iron, and glass), the reason behind Venezuela’s empty pavilion is anything but soothing. Yet the vacant space underscores the culminating dialectics of post-national capitalism that feeds the collapsed distribution of both senses and resources in this biennale, and beyond.

Moving Backwards (2019) by Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz. Installation with film. Photo by Annik Wetter.

Swinguerra (2019) by Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca. Film still. Image courtesy of the artist.

This is why I want to finish with a citation from Stockholm-based artist Santiago Mostyn’s lecture performance Notes on Influence (2019), performed in a villa close to Giardini—ironically enough purchased by an artist who thought that such an affair was a bargain compared to finding something in similar Stockholm. Yet, the internationally present undertone of Airbnb-punctuated housing politics wasn’t acknowledged in the midst of heads of institutions that stiffly contemplated Mostyn’s critique toward their right hand: normative art criticism, the media that since the enlightenment has distributed exhibitions beyond their architectures:

These men will keep going to work every week, keep reviewing exhibitions and cultural events, and keep assuming that their opinions are those of a culturally-sensitive intellectual, when in fact their opinions constitute one of the most insidious forms of resistance to social progress that we face.

The Venezuelan Pavilion. Photo by Frida Sandström.

The same goes, unfortunately, for the biennale as a construct. When the free drinks are over and the party costumes are exchanged for grey Maydays, the price winning beach in Lithuania has never been more absent, just as the tingling sense of the sublime felt when almost touching fabricated or filmed algae in constant sunlight. The news media goes on, still covering the dominant subject’s narrative of what just happened. I click myself though the reviews that pop up one after another on social media and randomly flip through the image section. In an ad, or perhaps it was a short review, I glimpse a generic face that looks like mine. It’s yet another white album.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Frida Sandström.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.