Turkish poet, playwright, and novelist Nazim Hikmet spent a life in exile condemning fascism, its accomplices and all the ills they saliently bring to people’s lives. Hikmet had a distinctly humanitarian communistic stance that spoke through his plays, stories, and poems, many of which were traditional folk matter. His plays are constantly produced; it is possible to find a Nazim Hikmet play on Turkish stages all year round, and it is safe to say that theatre people are gratefully and affectionately at home with all of Nazim Hikmet’s work. This is probably because his topics and interpretations never drift away or falter. It seems we simply can’t send some historical headlines to the waste bin.

To give a brief description of Hikmet’s plot in this work which has been widely adapted for theatre, a poet receives thirteen letters translated from Ethiopian to Italian from an Italian friend in 1930s. The friend, allegedly living in Mussolini’s Italy, has turned to African and Asian languages to quench his need to express himself, a risky venture in his mother tongue…The letters tell the story of the letters of an Ethiopian art student in Rome written to his wife back in Ethiopia, Taranta Babu. The poet’s friend finds these letters upon moving into the room formerly occupied by this Ethiopian art student, in a shanty-town hostel in Rome, and also that this young man was arrested the other morning for execution.

The letters are made up of poems, revealing in Nazim Hikmet’s feel of his day in the 1930s. They have the perspective of a young Ethiopian art student, observing the thirties’ fascism in Rome, and his letters have a wide range of topics to expose fascism’s ugly face blended with the sensibility of its victim, this Ethiopian student struggling to make sense of this vileness in this beautiful Renaissance city.

Nazim Hikmet (1902-1963), Turkey’s revolutionary communist poet, playwright, and novelist, wrote Taranta Babu’ya Mektuplar (Letters To Taranta Babu) in 1935 to protest Italy’s fascistic politics and the invasion in Ethiopia. Publishing the book caused the investigation that led to a twenty-eight-years prison sentence for his political views, upon which Nazim Hikmet left the country to start a life of exile. The book is organized as a beautiful collection of thirteen letters (two letters, eleven poems) addressed to the wife, Taranta Babu. Hikmet skillfully merges his play-writing and poetic licenses to create a dramatic setting for the letters–a worn-down hostel room to accommodate the unprivileged and the victim–and he creates the letters as lyrical poems of a husband, exposing the Italian affairs to a distant, unsuspecting wife. The letters celebrate the simplicity of the joys and the beauty of life yet they vividly express the reality of a corrupting system supporting the operations of fascism. As with the common left-wing sensibilities of his 1930s contemporaries, Hikmet’s work is a typical anti-war literature; an accessible, explanatory volume on the ugliness of totalitarianism and its fatal consequences, speaking to a population of low-brow, unprivileged, and even victimized audiences and readers.

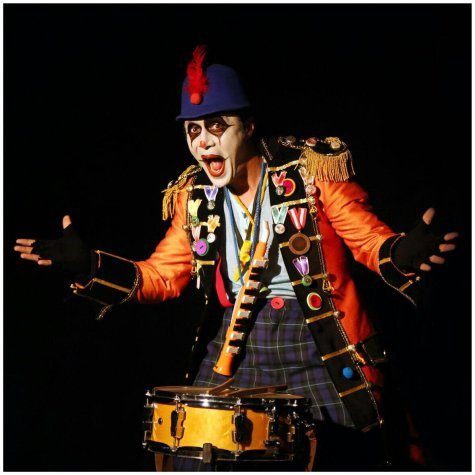

Hikmet’s work has been popularly staged in Istanbul in these last few years but actor Cansu Firinci ’s clowning version brings a breath of fresh air to the performative environs of Hikmet’s work that is slightly sinking under the heavy atmosphere of the current emotional and artistic responses to the state of affairs at home. Also, the naive clowning language is a better tool of satire as it is lighter and safer, and I believe more fully transmits Hikmet’s optimism and unwavering faith in humankind amidst all darkness.

The venue, a short production history, and an interview

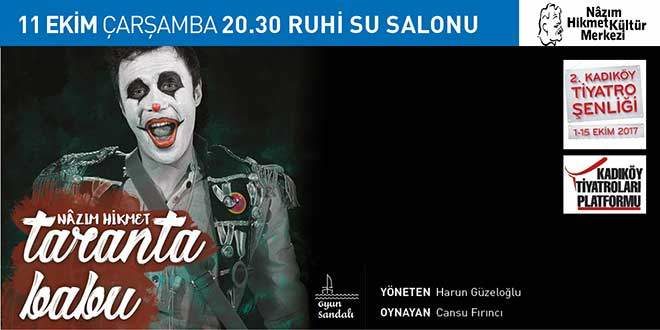

Genco Erkal of Dostlar Tiyatrosu (Friends Theatre– Theatre websites herein are in Turkish) has been performing poetry readings around the globe for almost two decades now, in a performance titled Insanlarim (My People), a collection of Nazim Hikmet poems, including passages from Taranta Babu’ya Mektuplar. The previous production of the same book for the stage belonged to an Istanbul theatre company, Oyun Isleri who performed it in one of Istanbul’s little theatres, Sahne Aznavur at Beyoglu, Taksim, to a small audience of forty or fifty people at most. Cansu Firinci performed his one-man clowning version at a similar stage, at Istanbul’s Asian downtown Kadikoy’s Nazim Hikmet Culture Center. Nazim Hikmet Culture Center offers a nice respite from the overly crowded streets of Kadikoy and has the pre-2000’s community feel to it with its bustling tea/beer garden, which is a rare thing in Istanbul nowadays due to recent anti-alcohol measures chasing spirits away from open public spaces to pubs and expensive elite locations. The center’s top floor serves as a tiny theatre with a minimal, raised stage and a meager space for an audience of thirty people at most.

In Pinar Tarcan’s interview (in Turkish) with the performer Cansu Firinci on December 9, 2017’s Biamag, Firinci refers to the late trends in Turkish theatre to seek smaller and more intimate audiences. For Firinci, the reasons for such alternative tendencies to gravitate towards these inhospitable, small spaces (for example with low ceilings, unaccommodating columns, etc.) are the closing of the greater theatre houses,and he also mentions the difficulty for the private theatres to compete with the state (national) and municipal (city) theatres as well as the high-end corporate venues. Firinci’s observations call to mind the little theatre movements but maybe with an eye for selecting its audiences, both for security and independence in its intimacy with this “little audience.” Furthermore, Firinci claims that such adverse conditions have been triggering creativity and increasing the quality of the performances. He adds that there is a small but solid spectatorship choice for these alternative stages.

Cansu Firinci performed the one-act play in the spring, and the director was Harun Guzeloglu. Firinci’s clowning trainer was Ezgi Keskin, and Nazan Celebci (ZeZe) designed the eye-catching clown costume. Visual, set and light design belonged to Alev Topal, Ozgur Sahin, Busenur Sevincli, and Harun Guzeloglu. Photos are by Tahir Enes Akbuğa. I hope to see this play again in the coming season, and I can bet it will be around for a long while…

Courtesy of Nazim Hikmet Culture Center website.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Bahar Karlıdağ.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.