Tracing its profile over the last 25 years unveils interesting changes in India’s only ancient Sanskrit theatre

When the performer shows the introductory gesture suggesting “a long time ago,” the Koodiyattam audience is taken down a grand rewind. So unhurried is the journey that to call it a flashback will be a misnomer. The pace—or the lack of it—of the very mudra that leads the viewer to a valid past is suggestive of the eye for detail.

Called “Nirvahanam,” it sets off a trip down memory lane, delving into every pertinent sub-story. Such an intense recapitulation is one highlight of this Kerala art form, the Indian subcontinent’s only surviving traditional form of Sanskrit theatre. Into the 21st century, Koodiyattam has for a while been finding vaster audiences in farther lands. That has gifted the form with all-round improvisations in the past three decades. A recent week-long Koodiyattam festival in Delhi held up another mirror, summarising a retrospective of its own new-age evolution.

Frontline artiste Margi Madhu, who led the team, notes that a key change is regarding body kinetics.

“The space consumed by an actor (irrespective of gender) is getting liberal by conservative standards,” he says, conceding that the torso has, nonetheless, been in stronger use since the 1960s when Kerala Kalamandalam launched a Koodiyattam wing.

Taut mudras

This could also be due to the proximity of the art’s masters to the dance-drama of Kathakali that enjoys pre-eminence in the central-Kerala institution, which first opened the gates to students beyond the Chakyar community that traditionally performed Koodiyattam.

“I’d say suppression (of the physique) is as integral to Koodiyattam as expression. When mudras get taut, there is an explosion in the movements.”

Kalamandalam Satheesan Maravanchery, who learned Kathakali make-up (chutti) at Kalamandalam in the 80s, often works with Madhu’s troupe.

“The paper-cuttings on the face are getting wider these days. The suggestions come largely from the younger ones,” he says, somewhat detachedly. “It’s fine if you have a sense of proportion. In Koodiyattam, they don’t line the eyes and brows as broadly as in Kathakali. The costume, too, is slimmer. Also, Koodiyattam artistes speak the dialogues; so a sleeker chutti is ideal.”

Unlike in Kathakali which has background vocals, Koodiyattam characters mouth the lines themselves. Not everything though, because there are episode-punctuating stanzas rendered by the woman artist on one side of the stage. Nangiar, as she is traditionally called, otherwise keeps the rhythm. Her taps on the tiny cymbals, sometimes with an assistant, lay the ground for the huge mizhavu drum and the idakka to roll out a grand percussion (with, in some styles, the timila drum and kurumkuzhal pipe).

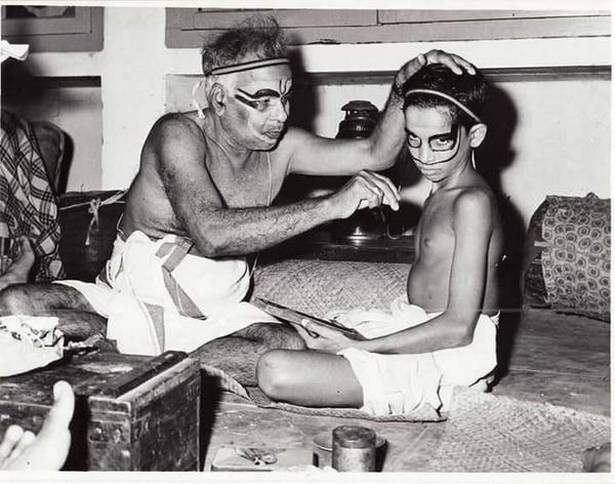

Make-up in the green room. Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

Indu G. says the shlokas she delivers today carry a streak of sensation vis-a-vis their tone a quarter-century ago.

“Not just with me; it’s there across schools,” she says. The reason? “Today, quite a few of us learn shlokas from Chakyars or male performers. The rendition is a tad more dramatic than what you’d learn under Nangiars.”

Modern touch

The female attire in Koodiyattam has also undergone a revolutionary change in the past 50 years, says Madhu, Indu’s husband. The facial make-up, too, has improved.

“Overall, the mythological women are looking increasingly like those in Raja Ravi Varma paintings. At times, they even look like the goddesses in Sivakasi calendars,” he says.

Young drummer Kalamandalam Manikandan says he is keen to generate realistic sounds on the mizhavu as well.

“Be it of a running horse or a gurgling stream, I go a bit off tradition.”

He attributes this to V.K.K. Hariharan, his celebrated senior. Idakka player Kalanilayam Rajan even extracts birdsong by squeaking the slender stick on the hourglass-shaped instrument.

Manikandan, who has been long associated with Madhu’s Nepathya, Centre for Excellence in Koodiyattam, founded in 2004 in Moozhikulam by the Chalakudy river, says his experiments have also to do with his work in contemporary plays. Madhu says that Koodiyattam has itself been gaining from modern theatre.

“The slowing of the (hand-held) curtain and the ceremoniousness of the retreat of the greenroom assistant who appears to pour oil on the lamp are examples of a borrowed cosmopolitan sensitivity,” he says. “So is the use of stage lights and back curtain.”

Aesthete Sudha Gopalakrishnan says those initiated in Hindustani Dhrupad music will find in Koodiyattam a similar meditative quality.

“That is one reason why we wanted to conduct the Surpanakhankam festival in Delhi,” she says.

Organized in collaboration with culture portal Sahapedia, the six-evening series held last month celebrated the second act of Sanskrit writer Saktibhadran’s Ascharyachudamani based on the Ramayana.

As Indologist David Shulman said, “Koodiyattam is seeing a growing return to the idea of wholesome performances,” in place of the heavily edited versions it presented in the 90s and 2000s in a bid for wider reach.

The Delhi-based freelance journalist is a keen follower of Kerala’s traditional performing arts.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Sreevalsan Thiyyadi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.