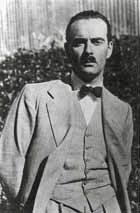

Lauro De Bosis (1901-1931)–the world’s only Olympic medalist in drama. The De Bosis Fellowships and Lectureships in Italian Civilization at Harvard are named in his honor.

Here’s a curious piece of theatre as well as Olympic history: It was on this day (July 28) in 1928 that the first and only Olympic medal competition in drama was held. Yup, Olympic drama. Oddly, only one medal was awarded–a silver–to Italian playwright Lauro De Bosis for his work Icaro, a retelling of the myth of Icarus as an anti-Mussolini allegory. No explanation was given for the lack of gold or bronze awards in drama during the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics, despite the full range of medals awarded in architecture, lyric work, epic work, music, sculpture and painting. (One wonders if De Bosis stood on the medal platform alone in second place and listened in silence while no winning national anthem was played and no winning national flag was raised…)

In fact, one of the original ideas behind the modern Olympics was to include artistic competitions along with the sporting events, similar to the ancient games. But, one by one, such competitions were dropped as the amateur status of many artists became too difficult for the Olympic committees to determine. Or at least that was their official excuse. By the 1950s the competitive arts had been completely eliminated from the modern Olympics just as the very nature of amateurism was being seriously challenged in the competitive sporting events. Given how today the modern games have abandoned any pretense of “amateurism” whatsoever, one wonders why artistic competitions haven’t been reinstated. While the argument could be made that it is impossible to judge artistry with any degree of objectivity, that certainly hasn’t prevented Olympic competitions in rhythmic gymnastics, diving, figure skating, and synchronized swimming. On the other hand, today’s Olympic anti-doping rules, stringently applied, might sufficiently reduce the field of eligible dramatists to such a degree that any competition would be superfluous anyway.

De Bosis, in advance of flying too close to the sun, was probably not overly concerned about today’s tough anti-doping rules. Nor was he overly concerned about his fuel gauge, evidently.

De Bosis, by the way, wasn’t just a one-hit Olympic wonder. He was a promising playwright and poet who earned international praise for his writings at an early age (Thornton Wilder, for instance, dedicated his novel The Ides of March to him). Unfortunately, De Bosis’ other passion was flying–where, evidently, his talents were decidedly less than Olympian. While distributing anti-fascist flyers over Rome in October 1931, his plane ran out of fuel. Just like the mythical character in his award-winning play, De Bosis crashed and died. Given the times and his political inclinations, however, it’s unlikely he would have survived to a ripe old age, even if he had properly managed his remaining fuel.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Peter Davis.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.