Regional editor’s note: Directed by Pamela Nomvete and Koleka Putuma, Venus vs Modernity is celebrated poet Lebo Mashile’s first play. Opera singer Ann Masina co-stars in the play alongside Mashile in the title role of Venus. The play centers on Sara (Saartjie) Baartman (1798-1815), a South African Khoekhoe woman of Gonaqua decent who was sold as chattel and became a curiosity in the human zoos of Europe. With her large buttocks and apparently remarkable sexual organs, she embodied colonial imaginings of race, sex, and sexuality (the Hottentot Venus). Some scientists speculated that she may be the missing link between humans and apes, exemplifying the supposed ‘truth’ of Western racial hierarchies and ideas of racial evolution. Being seen as closer to nature and lacking culture or civilization, she also confirmed the inferiority of her sex. After her death, her remains – including her brain and genitalia – were displayed in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris. The scientization of colonial scopophilia legitimized the inhumane treatment and sexual exploitation of the ‘other’, and Sara Baartman epitomizes this legacy. Baartman’s agency in her relocation to Europe and her exhibition-performances is much debated. Following South Africa’s 1994 elections, Nelson Mandela requested that Sara’s remains be repatriated to South Africa. On 9 August 2002, over 200 years after her birth, Sara was buried in the farming village of Hankey in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Her grave has been declared a South African National Heritage Site. (Marié-Heleen Coetzee)

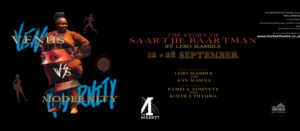

Sandile Memela reviews “Venus and Modernity” that recently had a run at the Market Theatre.

Sandile Memela reviews “Venus and Modernity” that recently had a run at the Market Theatre.

Venus vs Modernity tells the story of South African icon Sara Baartman whose horrific experiences of exploitation on account of her ample posterior have become a reference point for black women’s body image and representation worldwide. Directed by Pamela Nomvete and Koleka Putuma, with opera singer Ann Masina co-starring in the play alongside Mashile in the title role of Venus, Venus vs Modernity is an emotional, hilarious, poetic, musical and layered journey into the life of one of South African history’s most important women. This piece comes at a time when the country is on fire with conversations and protests on the issues of gender-based violence.

First-time playwright Lebo Mashile’s portrait of Venus as a “slave” or a self-determining woman African artist is neither exhaustive nor quintessential. What complicates the dramatic narrative is the awareness that even in oppression, slaves or the oppressed remain multi-faceted human beings with human agency. They have a choice: submit or fight.

It would be unfair to say playwright Lebo Mashile went out of her way to imprison Venus in a single determinate box. It would seem five years or research has made it difficult to interpret Venus singularly as either a slave or a free agent. In fact, Venus is not a single narrative story that puts her into the predictable box of a slave.

What was admirable and courageous, for me, was that Venus vs Modernity does not take short cuts to oversimplify this complex historical experience. No doubt, Venus is both a “slave” and a complex self-determining artist working in a hostile environment.

There were moments when I was tempted to dismiss the work for its predictable “preoccupation with race.” This ‘race obsession,’ if you like, tends to unavoidably reduce and project Africans into hapless victims of white supremacy. This tendency is counterproductive as it denies the power of human agency and undermines the humanity of Africans as people with creative intelligence and the power of choice. Of course, considering that this is a 19th-century historical experience, race had to be a primary subject. Indeed, Sara Baartman was reduced to the Other.

However, is it not political reactionary, for anyone, to just portray or restrict her to that. Questioning this outlook does not necessarily deny or downplay the impact of racism. We have also to consider the position of Africans who collaborated and thus were part of the racist system. Uncomfortable as it seems, there are and always be Africans who benefit from slavery and economic exploitation today.

Mashile and the creative team are correct to locate Venus in the social milieu of stereotypes and prejudice that projected racist attitudes. Yes, Venus was inevitably affected by her circumstances as much as she was an agent who defined her age.

What this means is that – just like today in contemporary South Africa characterized by economic injustice – African artists have a choice to either confirm the status quo for their individual benefit or oppose it. Venus raises and echos very complex themes that are pertinent to today’s realities.

The drama is immediately linked to the lived experiences of African women and the prevalent gender-based violence they are subjected to. The reality is that African women – and all women in general – are subjected to this patriarchal violence. But are they the only ones? What do they do about it in terms of agency, resistance, and opposition? Hence the complications of a single racial narrative than a human story to reflect social realities in the world today.

Lebo Mashilo and Ann Masina in “Venus vs Modernity”. Photo: Sandile Memela.

A further complication – you can call it artistic license if you like – is the assumption that all men are patriarchs, for example. Of course, Venus was duped by a male manager and showbiz promoter. But there were presumably many women and children in the audience who attended the “freak shows” that featured some white women, too. This is where one hungers for a more complicated human story than one that collapses into predictable racial monotony. Venus comes very close to that.

Not all Africans were “slaves” in the sense of being ridiculed, mocked and humiliated. Embedded in history is the fact that there always was a distinct group that was cashing in from this dastardly phenomenon. Mashile and her creative team try very hard to not make this the thrust of the Venus narrative: blacks were/are slaves. There is no mention of black slave owners or those that traded in this business.

It is very important to write from an African perspective – whatever that means nowadays – but we must flesh out human agency and freedom of choice in African narratives. This tendency to be, generally, one-dimensional in pointing fingers at white society is not helpful. Perhaps the shortcomings are that they all seem to agree to embrace and project the victim syndrome.

A young female seated next to me laughed derisively when I suggested that males are also victims of patriarchy. I cited the tragedy of Marikana and the number of men in prison or killed by males, for example. But this was brushed off as irrelevant to the Venus single focus on the historical experience of African women.

There is an urgent need for a paradigmatic shift in African storytelling. It was disappointing, though understandable, that Mashile and the team did not take the leap. If we consider that Sara Baartman was not in chains when she left Cape Town for London, we may at once imagine that she used the power in her hands to make a free choice to pursue international stardom. What cannot be denied is that she was a major attraction and trendsetter in her own right; a “superstar” in her own right in those hard times.

Of course, the much-vaunted anti-slavery Abolitionists have created a historical context with the single narrative of a victim that needed “friends of the Natives” to come to the rescue.

Can we for one moment imagine that Venus was neither a hapless victim nor a puppet?

If we want to go further, can we think of her as an African artist who tried to make the best of a bad situation as our creatives continue to in this post-modern age.

Let’s shift the focus a bit to consider the issue of the target audience. To whom does Mashile and team address themselves and what is their key message? Certainly not the ordinary female African who is caught in the pincer grasp of racism and capitalism. The play is more directed, methinks, to elite African/black women who are working in a white anti-black world and have, increasingly, become vocal. Above all, this is a production that is going to Europe to show and presumably highlight Venus’ plight to some decedents of former slave owners.

Venus, for me, opens up the dilemmas of African artists today.

It was enlightening when world-traveled singer and principal actor Ann Masina testified about the problem of a full-bodied African woman artist. It is not that her talent is not recognized but that much as she brings delight to the world, she is still seen as the Other, less human because of her physical features. The recognition of this fact matters because the female African artist exercises power to work within a racist patriarchal system for money or to find ways to oppose it to raise political consciousness among her community.

In the end, Venus vs Modernity is an attempt to convince especially Europeans, that African women are not half-humans or sex objects but people created in the likeness of God and deserve to be treated with dignity.

It is a relational play instead of a declarative production that simply asserts: I am a human being and I dont have to explain myself to racists. As a result, it is reactionary, oppositional and liberatory within the framework of a supremacist, patriarchal, exploitative and racist economic system.

It contains some philosophical insights that transcend obsession with race and some ideas from which high caliber female African creative can afford to be true to themselves and forget about living to white expectations. In short, Venus vs Modernity can be described as being about “black in an anti-black world.”

But what about African self-determination, freedom of choice and human agency?

African woman creatives cannot be conscious and still define themselves through the lenses of white European eyes. Their duty is to be true to themselves when they tell their stories and write their history.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Marié-Heleen Coetzee.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.