Of all the great Russian writers of the second half of the nineteenth century, none perfected the art of dualism quite like Anton Chekhov. The tragic and the comic, the internal and the external, the serious and the trivial, the lived and the imagined–in his work all coexist and converge; the borders between them shift, erode, lose all meaning. From a forest of easily caricatured sureties–Turgenev’s naïve liberalism, Tolstoy’s confident religiosity, Dostoevsky’s impassioned conservatism–Chekhov emerges as a torchbearer of uncertainty, moral ambiguity, and nuance. Like Schrödinger’s famous cat, at once both alive and dead, Chekhov’s characters and themes defy categorization.

An inevitable conflict thus emerges when Chekhov’s works are produced for theatre or film: opening the box and revealing Schrödinger’s cat to be alive and purring is sure to alienate those who were convinced it was dead, not to mention those for whom the cat’s status as both alive and dead was key to their infatuation with it. This presents enough problems for those works that Chekhov himself wrote as plays–most notably The Cherry Orchard, which has long been the subject of lively tragicomic debate–but adapting one of his prose stories for the stage is a whole other task.

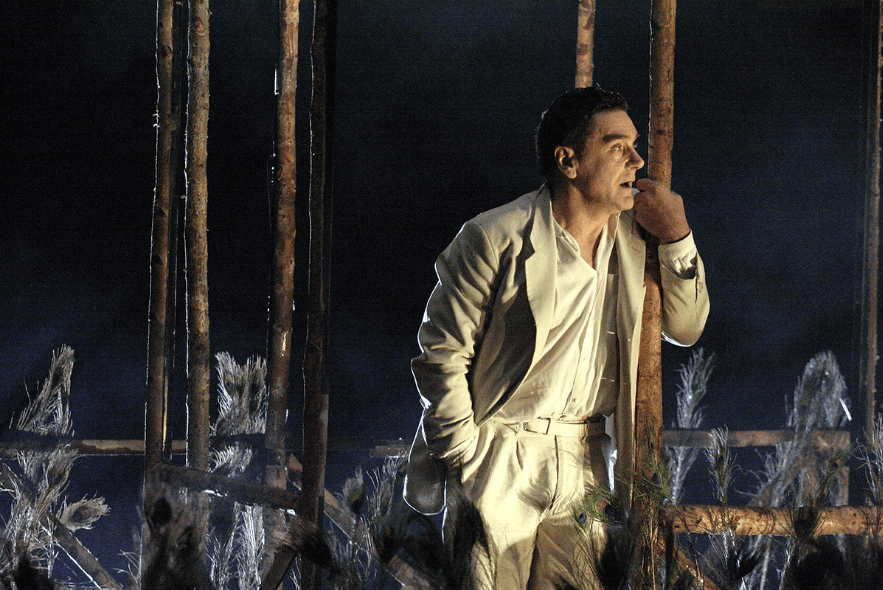

Take The Black Monk, the subject of an award-winning theatre adaptation by Kama Ginkas, a recording of which I saw at Pushkin House last weekend. Written in 1893, the story follows a young academic, Andrey Vasilyevich Kovrin, whose repeated encounters with a hallucinatory monk lead first to inspiration, confidence, and love, and later to despair, marital breakdown and–ultimately–death. Inevitably, the story brings up a host of questions destined for eternal debate: Do the narrator’s sympathies lie with Kovrin or his wife and father-in-law? Is the eponymous monk an inspirational muse or demonic phantom? Are Kovrin’s hallucinations the symptoms of madness, or the inevitable by-product of a brilliant, creative mind?

When it comes to adapting for the stage, one way to deal with all this ambiguity is to include as much of the original text as possible, a tactic that Ginkas has taken to the extreme by including most of Chekhov’s narration in the script. Each character speaks not only their lines, but also narrative embellishments right down to “he said” and “she said.” My reaction to this innovation has a touch of Chekhovian dualism to it: on the one hand it can be seen as a comment on the subjectivity of all lived experience, the way in which each individual constructs their life-story through personal narratives; on the other, it’s a gimmick that, over the course of a two hour long play, starts to grate a little, which lets you wonder exactly how much it was intended for displaying the social construction of reality, and how much for earning a few cheap laughs.

The balance of the dramatic and the comic is my chief criticism of the production. There’s certainly plenty by way of comic relief in Chekhov’s original story, especially in the trivial obsessions and erratic familial relations of the Pesotskys–Kovrin’s hosts and later in-laws–which comes across well in the play but is needlessly embellished by a large dose of slapstick. It’s the early appearances of the monk, though, which are most off-pitch. The monk appears here like an apparition from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, spritely, gregarious and almost unambiguously comic. While this gaiety is tempered with some dramatic music and lighting, the overall effect is one of cognitive dissonance rather than tonal nuance.

The scenery is superb, with the Pesotskys’ famous garden beautifully and minimalistically rendered in a rich palette, and there are certainly some worthwhile moments, such as when Kovrin leafs through his father’s pile of tedious journal articles with a delightful mixture of ridicule and pathos, and in particular the finale, where the monk breaks through the walls of Kovrin’s unconscious to confront him one final time; I only wish that some more of this dramatism had been applied to the rest of the play.

This article originally appeared in CEEL.ORG.UK on March 29, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jonathan Karstadt.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.