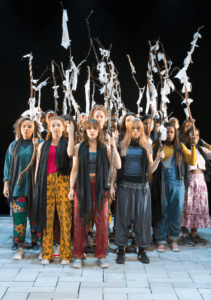

Lizzie Clachan’s set is a simple stone floor slanting downwards towards the audience in a warm glow of anticipation. There is a frame at the back of the stage through which we first glimpse a chorus of women tentatively inching their way into view, holding aloft tree branches with pieces of white wool wrapped around them. The bandaged branches –making them look like a bedraggled sailboat on the horizon–is a sign of their good will and a visual symbol of their plea for protection.

Unusually for an ancient Greek play, Aeschylus’s The Suppliants is a play in which the chorus is a main protagonist. Even more unusually for a modern production of a Greek play, this version, co-produced by Actors Touring Company and the Edinburgh Royal Lyceum seizes exactly on this opportunity provided by the play.

The Company in The Suppliant Women at the Young Vic. Photo Credit: Stephen Cummiskey

For context, it is perhaps worth noting that this production follows on from a previous success created by the tandem of writer David Greig and director Ramin Gray The Events (2103), a piece partly prompted by Anders Breivik shooting in Norway in 2011. In a fashion that distinguishes the current production too, the original two-hander featured a notable presence of a community choir woven into the dramaturgy of the piece.

The story of The Suppliant Women is pretty simple–they flee from Egypt to Argos to escape arranged marriages. The Argive king Pelasgos is at first reluctant to give them the refuge they seek for fear of provoking war, but then proposes a referendum. Being mounted in 2016, this production was a direct response to the refugee crisis of Europe reaching its peak at the time. The production opened in Edinburgh in the summer of 2016 to great acclaim. Far from sheer tokenism, the show’s recruiting of the chorus of women from the local community in Edinburgh formed part of its central idea of theatre as a democratic medium, which the creative team was attempting in an instance of “theatrical archaeology.”

Evoking the social function of theatre in ancient Greece, therefore, the piece opens with a roll call of detailed statistics regarding the exact amounts of money each audience member and each tax-paying citizen contributed towards the making of the piece. This is followed by the pouring of libations, often by a distinguished member of the community or a politician on each occasion. The formalities quickly give way to David Greig’s startlingly luscious poetry. The piece has a distinctly ritualistic feel from the outset; all speech is audibly metered and, as such, flows into a continuous chant. The whole duration of the show is underscored almost without interruption by John Browne’s musical accompaniment consisting of a modern version of the ancient instrument aulos and various kinds of percussion.

Particularly memorable moments have the women engaged in acts of deep solidarity–drawing mythical beings on the surface of the stone floor, vowing collective suicide if their honor is at stake, keeping vigil, waiting. Eventually, this gives rise to an ecstatic frenzy of celebration at just the right time. Choreographer Sasha Milavic Davis and voice coach Mary King deliver technically crisp and artistically sophisticated ensemble work, demonstrating a way in which the director’s main accomplishment in a piece might simply be to create a self-sustaining mechanism for showcasing the talents and creativities of others. Both in terms of form and content, this production of The Suppliant Women is a triumph of womanhood and not only because it ends on a rousingly high note, quite literally calling for the powers that be to “Give equal power to women!”

The Community Chorus in The Suppliant Women at the Young Vic. Photo Credit: Stephen Cummiskey

Following a national tour whereby a new chorus of local women has taken center-stage every time, the production has just reached London and it seems difficult to ignore the ways in which it has aged since its initial premiere. Over time the news of Syrian refugees has been replaced by Brexit and Trump and sexual allegations against powerful men in show business. The piece structured around the very notion of resistance to patriarchy retains its core relevance under these new circumstances, but suddenly the fact that the Suppliant Women have fled in the company of an older man or that his sage advice warns them of the danger of their own nascent sexuality reads differently, at times even turns Grieg’s sensual verse into something sounding like lechery.

As an additional layer of complication, at the time of writing, fresh new allegations have emerged against the show’s own director Ramin Gray. Ironically, these allegations, concerning the director’s past, have occurred in response to Gray’s own criticism of male abuses of power. Gray has not responded to the allegations as yet and was reported absent from the final week of rehearsals at the Young Vic.

If good theatre teaches us anything, then it is the fact that there are no easy answers to moral problems in life. As a species, we are bound by contradiction and must contend with it. And ultimately, given choice, each one of us would prefer to have an opportunity to reach and voice our own opinions than to be told what to think. In Aeschylus’s polytheistic world, multiple worldviews sanctioned by allegiances to different gods can be seen to be forced to co-exist without resolution. As Aeschylus would have us know, in the interest of the natural world’s survival female god Aphrodite demands sexual union between men and women while the Suppliant Women appeal to the male god Zeus for justice, moral dignity, and political equality. Aeschylus’s world itself, then and now, has always adhered to the deeply entrenched power mechanism of patriarchy, and this production authored by men remains within it even if its rallying cry brought about by the women working on the show has us feeling otherwise. By all accounts, therefore, the best take-home message we can hope for at the moment must amount to that other gift the Greeks have given us–the virtue of dialectic thinking.

Text: David Greig after Aeschylus

Direction: Ramin Gray

Music: John Browne

Choreography: Sasha Milavic Davies

Voice coach: Mary King

Design: Lizzie Clachan

Light: Charles Balfour

Assistant Direction: Alice Malin

Cast: Oscar Batterham, Omar Ebrahim

Chorus leader: Gemma May

Musicians: Callum Armstrong, Ben Burton

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Duška Radosavljević.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.