A son and his mother, a mother and her son. What are some of the first thoughts that come to mind? For me, there’s Proust’s Marcel, writhing in agony because his mother did not bestow her customary goodnight kiss upon him when he went to bed. Then there’s Anthony Perkins’ Norman Bates, dressed as his dead mother to commit crimes against the objects of his own libido in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. The interplay between mother and son may be inherently dramatic.

Add to that company Arturo Luís Soria’s provocatively comic Ni Mi Madre, a one-hour, one-man-show now playing at Teatro Sea as part of the Rave Theater Festival in New York City. Soria occupies the body and soul of his mother, recreating the world as she sees it—which includes commentary on her relation to her gay and hyper-theatrical son, Turo.

To see what Proust called “the profanation of the mother” coupled with performance of or as the mother is to wander in a space that might give a Freudian profound pause. Once upon a time, a son playing his mother might have offered a tightrope walk between gender identities, but here the mother’s indulgence toward her son—seemingly the favorite of her five children with three different husbands—is made performative by the son’s attachment to his mother’s “drama.” Together, they are a symbiotic gestalt that the play exists to entertain us with.

And yet the indulgence on both sides makes for an important dramatic tension. If not exactly a “profanation,” in Proust’s sense, where the mother’s fondest wishes will be frustrated by the son’s inability to honor them, here Bete’s frustration, as an abiding theme of the play, keeps us wondering what—besides our attention—could make her happy. Maybe if her son makes her famous?

For Bete, female artists/celebrities like Madonna, Angelina Jolie, and Meryl Streep have what it takes, but they also don’t quite have what Bete has and if her life had gone differently she would be their equal in fame and name recognition. At times, her monologue can seem ready to become a stand-up routine as she pigeonholes her husbands and children with epithets that make everyone in her life less colorful background players to her starring role. Turo gets an important supporting role, and the main antagonist is Bete’s own mother, dramatized through a few key scenes that underscore how different they are. We see how important it was for Bete to get away from her mother’s influence, and how certain comments by her mother—such as “you’re your father’s child, not mine”—even if efforts to save face, leave wounds.

Bete likes making claims for her vagina, the source of power which made her a mother. And she likes to point out that being a mother is her major identity—with most of the show’s comedy coming from how she enacts her maternal role. She’s a tough mother, a Brasileira, not only not afraid of using corporal chastisement but not apologetic about it nor apologetic about not being apologetic. She’s a force of nature in her own mind and tells her stories to underline that fact. All her children owe her their existence and any whining or bitching about how she treats them or speaks of them is, in her mind, still to her credit. The first thing they have to understand is that she is their mother—and what that means. Without her, they wouldn’t even be here.

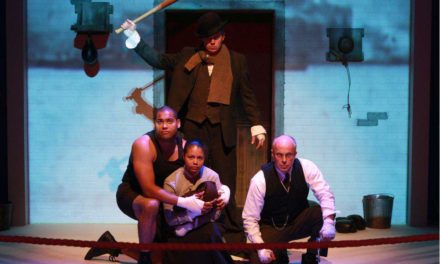

In many ways, the pathos of Bete is the pathos of any woman who lives primarily through her children, and that dependent relation is made manifest in Soria’s wonderfully engaging performance. Her son might become her, becomingly, but that only underscores his power over her. What she might like most is to become him, and that staged fantasy leads us through the world of her memories, her grief and her glee. We might not always be charmed by Soria’s madre, and some may even by put-off by her forthrightness, but her theatrical presence is never in doubt. She makes each anecdote vivid and when she stands with a toy boat full of bric-a-brac as in offertory, the implied consecration is real. The mother becomes the son, the son the mother, and never more so than when the mother’s mother, a fearful ancestor, is evoked.

Soria, a recent Acting graduate from the Yale School of Drama’s MFA program, is also a gifted playwright, with a good ear for speech rhythms. Ni Mi Madre is directed for the second time by Danilo Gambini, a rising third-year at the Yale School of Drama, with a very fluid sense of timing and movement. Both worked on the piece at Yale Cabaret in the 2017-18 season and a number of YSD grads are on hand. Kathy Ruvuna’s sound effects and lighting by Krista Smith and Nic Vincent on Stephanie O. Cohen’s spare but colorful set, help to create a space for Madre’s convincing bid for theatrical glory.

Ni Mi Madre

Written and performed by Arturo Luís Soria

Directed by Danilo Gambini

Dramaturg: Madeline Charne; Producer: Leandro A. Zaneti; Stage Manager: Fabiola Syvel; Set Designer: Stephanie O. Cohen; Costume Designer: Mika Eubanks; Lighting Designers: Krista Smith, Nic Vincent; Sound Designer: Kathy Ruvuna; Graphic Designer: Neo Avila

Rave Theater Festival

Teatro Sea Theater

The Clemente Soto Velez Cultural Center

107 Suffolk Street, New York NY

August 9-25, 2019

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Donald Brown.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.