When was the last time you looked at a stranger in the eyes? Really looked, for an uncomfortably long period of time, recognizing something about them and yourself in the process? Probably not recently. In a pandemic world, it is becoming harder – if not impossible – to connect with other people on such an intimate, vulnerable level.

The Museum of Modern Love, adapted by Tom Holloway from Heather Rose’s Stella Prize-winning novel, explores what it means to gaze deeply at another person and recognise their shared humanity.

The play centres on a composer, Arky Levin (Julian Garner), and his unfathomable choice not to visit, sit with and look at his wife Lydia (Tara Morice), who is dying in a nursing home.

Like his namesake Konstantin Levin from Anna Karenina, Arky needs to have a divine moment of transcendence to find the courage to connect to his beloved.

While Konstantin’s realisation is religious in nature, Arky’s moment of truth comes in the form of performance art.

The artist is present

Rose took inspiration from the Serbian performance artist Marina Abramović’s epic endurance work The Artist is Present (2010).

Held in New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Abramović sat in a chair for eight hours a day for 75 days. As she sat, strangers could choose to sit and stare into the artist’s eyes for as long as they liked. But they could not speak, nor touch.

Over the 75 days, 1,545 people sat in front of 850,000 spectators.

Audiences are invited to look – but not touch. PC: Ten Alphas

For the sitters, it was reportedly a sublime moment of recognition: they laughed, they cried, and they were transformed through the simple act of maintaining eye contact with Abramović.

Holloway’s The Museum of Modern Love returns to this performance artwork to make a moving case for the importance of not just actively engaging with art, but actively engaging with each other.

Who watches the watchers?

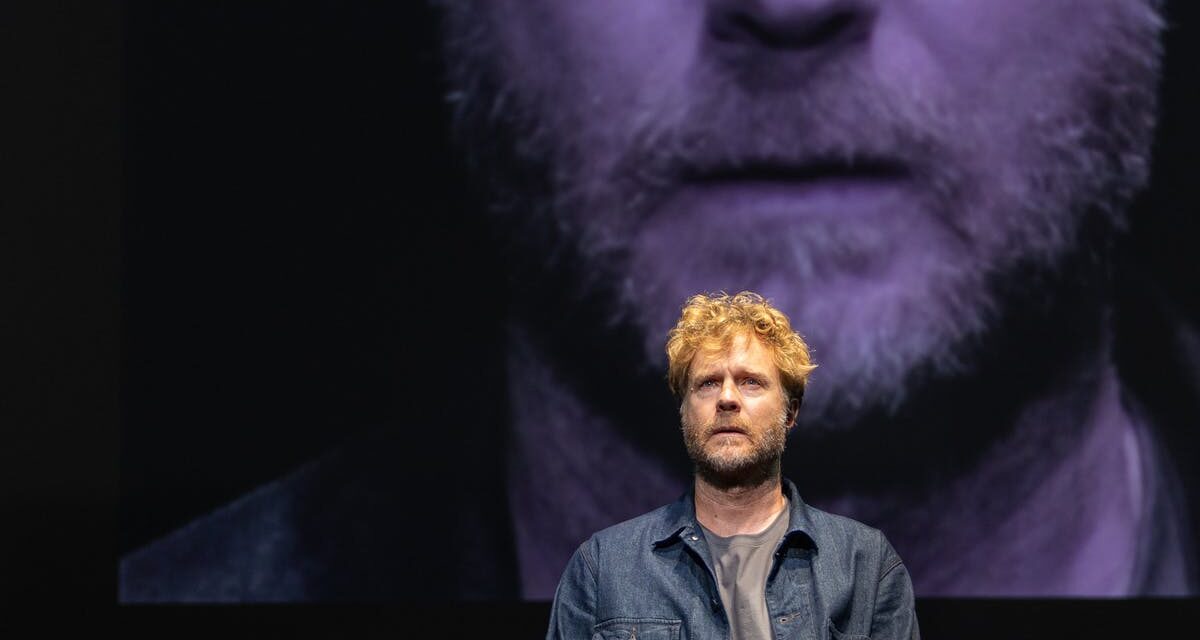

Much of the play is set in MoMA. As the audience in Sydney’s Seymour Centre, we watch the art gallery patrons watch Abramović’s sitters (like Godot, we never see Abramović herself). The cast also joins us in this watching: when not performing, they sit on the stage’s edges, gazing on the action within.

At times, the production is at risk of becoming a play about wealthy New Yorkers having existential crises. It is at its best not when Arky is at its centre, but when the MoMA attendees stand around discussing Abramović.

Holloway captures the lovely and absurd conversations which can occur in an art gallery. PC: Ten Alphas

Holloway captures those sorts of lovely, absurd conversations you might hear in an art gallery: about gaze as desire, loneliness, the value of art in society, and that eternal question: “is this even art?”

At some points, these conversations stretch the limits of credulity. In real life, no one speaks like they are in a novel about art. But to hear this sort of navel-gazing discourse is why we engage with art in the first place: to imagine the impossible.

While the characters talk, their faces are projected in close-up at the back of the stage, moving in slow motion, as though they are before Abramović. This draws our attention to the effect (and sometimes awkwardness) of watching: exactly what the theatre audience was there to do.

Behold

Theatre is a uniquely predisposed artform to have audiences question what it means to watch and look.

The word “theatre” derives from the Ancient Greek theasthai, which means, in its most simple definition, “to behold”. But more than this: theasthai suggests gazing at something with intent and acknowledging what you’re looking at can have an emotional effect upon you.

Going to the theatre is never a passive act. An audience should expect to be moved, even transformed by what they are watching.

An audience should always expect to be moved. PC: Ten Alphas

During The Museum of Modern Love, there was laughter, sighing, even an audible “eugh!” of recognition from one audience member when a character revealed she is a PhD student. The performance was a powerful reminder of the civic importance of the performing arts in bringing people together for a few hours of beholding, of contact.

The Museum of Modern Love wants to draw our attention to the power, and purpose, of performance. As one character asks: “what good is art without the people to be moved by it?”

It is a particularly pertinent question in our post-pandemic world.

The Museum of Modern Love plays at The Seymour Centre as part of the Sydney Festival until January 30.

This article was originally posted by The Conversation on January 27, 2022, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Gabrielle Edelstein.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.