Para Site, one of Hong Kong’s leading contemporary art spaces, is famous for its sprawling, conceptual exhibitions that tackle big ideas such as technology, colonialism and humanity’s mistreatment of the natural world. So the subject of its next show may raise some eyebrows: celebrity culture.

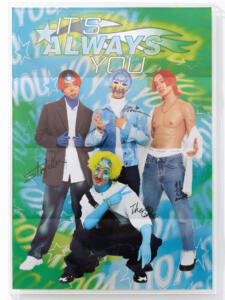

“I think a lot of institutions want to curate shows with grand jargon and big concepts, but sometimes for the audience that can be very intimidating. I wanted to do something different, to connect with a younger generation through a topic that is more approachable,” says Cusson Cheng, assistant curator at Para Site and the curator of Fanatic Heart, an exhibition running until February 26, 2023 that explores the complexities of modern-day fandom. The show features 15 artists whose work explores celebrity culture in Asia, including Sin Wai-kin, who is showing a series of works featuring members of a fictional boy band; Ho Tzu-nyen, who appropriated clips from films starring legendary Hong Kong actor Tony Leung Chiu-wai to create a new video, The Nameless; and Yasumasa Morimura, who makes photographic portraits of himself dressed as celebrities and icons, such as Audrey Hepburn, Marilyn Monroe or the Mona Lisa.

Cheng was inspired to curate the show after witnessing the mania that has built over the past few years in Hong Kong for the 12-person Cantopop boy band Mirror, who shot to fame in 2018 after winning ViuTV’s talent competition, Good Night Show—King Maker. They have since had a series of hit songs, appeared in reality shows, acted in TV dramas — such as Kearen Pang’s film Mama’s Affair — and secured endorsement deals with nearly 200 brands, ranging from McDonald’s to Cartier. Much about Mirror, including the hysteria the band induces among its fans, has been compared to the K-pop groups that have become global phenomena over the past decade, such as Big Bang, BTS and Blackpink.

Mirror’s enormous popularity in Hong Kong has led to the emergence of the term the “Mirror effect,” which references the band’s positive impact on the city’s economy during the Covid-19 pandemic. ViuTV experienced 152 percent year-on-year growth in revenue from HK$317 million in 2020 to HK$800 million in 2021, with advertising revenue more than doubling to HK$615 million. PCCW, which owns ViuTV, also saw business from artist management and events surge almost tenfold in 2021. HSBC, which featured Mirror member Keung To in a campaign targeting young people, told the South China Morning Post that millennials accounted for more than half of new customers for the service endorsed by the star. Their overall effect on the economy is staggering: an economics lecturer at the University of Hong Kong Business School, Vera Yuen Wing-han, estimated that Mirror could generate economic benefits of HK$5- to 10 billion per year for at least five years.

Although Mirror’s success is unlike anything else in Hong Kong in the past decade, this is not the first time the city has been consumed by celebrity culture. “Evidence shows that in the 1960s and 1970s, a fandom developed for the film stars of Cantonese-speaking cinema such as Josephine Siao and Chan Po-chu. Supporters established their own networks to circulate and publicize materials of their idols,” says Dorothy Lau Wai-sim, an assistant professor at the Academy of Film at Hong Kong Baptist University, who has extensively researched fandom in East Asia.

The public’s interest in celebrities increased further in the 1980s and 1990s, when the tabloid press emerged in Hong Kong. This partly led to what is referred to by pop culture scholar Stephen Yiu Wai-chu, the author of Hong Kong Cantopop: A Concise History, as “the heyday of Cantopop” in the 1980s and 90s. “Icons like Alan Tam, Leslie Cheung, and Anita Mui gained huge fan followings,” says Lau. Other stars who rose to fame at the time were singers and actors Andy Lau, Jacky Cheung, Leon Lai and Aaron Kwok, who collectively became known as the Four Heavenly Kings of Cantopop. The moniker for those four heartthrobs may have been taken from Buddhism, but it was their earthly activities their fans wanted to read about in the tabloids. “Fame was no longer merely defined by profession and work but also by lifestyle and romantic relationships,” says Lau.

The turn of the millennium saw the public’s engagement with celebrities ratchet up even further because of the impact of the internet. Social media has allowed celebrities to take some power back from the tabloid press because stars can now share their own news, whether personal or professional, directly with fans, rather than having to use the media as a messenger. For fans, social media has opened up a whole new world in which they can follow their idols’ movements every minute of every day. Fans can comment directly on celebrities’ posts and even message them personally, whether those messages are ever read or not. Social media has created a new level of intimacy between stars and their fans — and encouraged a new level of mania, too. “Celebrity culture has become more and more intense in Hong Kong, as in many regions around the world,” says Lau.

This has resulted in fans expressing their devotion in ways that go far beyond buying concert or cinema tickets. In 2021, fans of Mirror member Keung To banded together to sponsor free rides for all across Hong Kong’s tram network on their idol’s birthday, April 30. The estimated cost was roughly HK$2 million. Three months later, in July, fans crowdfunded more than HK$1 million to plaster their birthday wishes to Anson Lo, another Mirror star, on billboards and buses around the city. When Lo released a solo single, “Megahit,” last September, his fans took their efforts global, paying for a billboard for three days outside Westfield Stratford City in London, which is the largest shopping center in Europe.

If Revolution is a Sickness, 2021, by Dian Severin Nguyen.

It is not only obsessive teenagers driving these efforts. One of the ways celebrity culture is developing around the world, including in Hong Kong, is that fandoms now often include people of all ages. “Consider Mirror’s Keung To, whose fan base is wide enough to include teenagers, young adults, mature adults and seniors — people aged 70 to 80,” says Lau. Some of these older fans have been inducted into Mirror mania by their children or grandchildren. Others are drawn to the band because it reminds them of happy memories of their own youth, perhaps the era of the Four Heavenly Kings, or because they believe Mirror is a much-needed success story for Hong Kong, which since 2019 has been rocked by political unrest and a pandemic. A New York Times article about Mirror was titled simply: “This boy band is the joy that Hong Kong needs right now.”

As Mirror has shot to fame, the band has been dragged into the political debates swirling in Hong Kong. Some fans have expressed pride that the band sings in Cantonese at a time when some Hongkongers believe the language is under threat from increasing use of Mandarin in the city. Others have gone even further, interpreting Mirror’s ambiguous lyrics as coded pro-democracy anthems. Mirror members themselves have not made any overt political statements and have supported the government on certain initiatives, such as public health campaigns. But Lau says that Mirror, and all celebrities in Hong Kong, are likely to be interpreted as political symbols, whether they take a public stance or not. “While politicized celebrity culture is a global occurrence, Hong Kong celebrities have distinctive and contested relationships with mainland China and Taiwan because of social and political history,” she says. “This makes Hong Kong celebrity culture, and fan culture, loaded with long-standing issues.”

This is partly what inspired Cheng to curate an exhibition about celebrity culture. He says that the celebrities that societies become obsessed with, and the ways in which fans express their devotion, reveals a lot about the socio-political context of a place and its people. “Celebrities embody our desires,” says Cheng. “By looking at objects of desire, you can trace what communities are going through.”

Santacruzan, 2022, by Jonalyn Macalalad Molina.

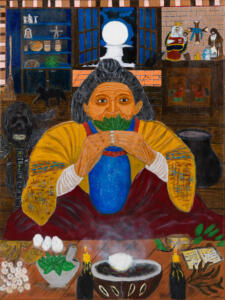

Babaylan—The Healer Shaman by Maria Christina Castillo.

The Feast of Black Nazarene, 2022, by Marilyn Santiago Lopez.

In many places around the world, including in Hong Kong, the widespread use of social media and celebrities’ ability to help people temporarily forget social, political and economic challenges has driven fandoms to such a fever pitch that they can be compared to religions. “Celebrity culture can incite obsession and acts of worship,” says Lau. “It is [often] associated with the idea of a cult.” Cheng has explored this idea in Fanatic Heart. Guhit Kulay, a collective of Filipino artists, has contributed several works to the show that include Christian imagery that, in the context of the exhibition, make explicit the links between celebrity fandom and religious fanaticism. South Korean artist Dew Kim also references religious iconography in his installation, which includes a mock stained-glass window, inspired by Christian churches, that features the artist dressed as a K-pop star.

The exhibition also examines the connections between celebrity and capitalism. Companies increasingly enlist celebrities to help sell their products, but public missteps can see stars tumble out of favor, which reduces their value to corporations, or sometimes even pulls brands down with them. South Korean sculptor Haneyl Choi explores stars’ value in one of his works in Fanatic Heart, which includes a series of keychains featuring a fictional boy band. Visitors can take home a keyring of their choice, so the number of souvenirs left will indicate how popular — or not — this fantasy boy band is with gallery-goers. The work makes visible the band’s value just like a stock exchange reveals the rise and fall of a company. “There’s now the term ‘fan economy’ to try to measure how much fans financially invest in their idols,” says Cheng. “Things change very quickly. Fandom culture is very volatile.”

Fanatic Heart is an attempt to explore the complex cocktail of factors that have led to today’s obsession with celebrity: the political climate of a place, which can lead people to latch on to a celebrity as a symbol of their culture, or a blissful escape from social challenges; the explosion of social media, which has allowed fans to follow their idols’ every move; and the fact that celebrity culture is now capitalized upon by corporations, which push stars into the public consciousness through advertising and endorsement deals. Ultimately, the show argues that celebrity culture reveals truths about broader society. “The exhibition looks like an elixir of pop culture offerings, but it’s actually about providing an alternative gateway to reconnect with social and political landscapes in Southeast Asia and East Asia,” says Cheng. “Celebrities are an embodiment of what is happening in a certain geographical and temporal location.”

Fanatic Heart runs at Para Site until February 26, 2023. Click here for more information.

Correction: This story was amended after publication to reflect the fact that Haneyl Choi has made two works for the exhibition, not one.

This article was originally published by Zolima City Mag on December 23, 2022, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Oliver Giles.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.