The lobby of the Setagaya Public Theatre in Tokyo teemed with women on Sept. 1, each eager to see Kei Tanaka in action. The 34-year-old actor — and judging by the buzz in the lobby, bona fide dreamboat — recently captured hearts in Ossan’s Love, a TV Asahi rom-com in which he played a cute gay salaryman.

If the women were there to see something similar, however, they were in for a surprise. Tanaka is currently starring in a Japanese stage version of Swimming With Sharks, a dark U.S. comedy that some critics have described as the male version of The Devil Wears Prada.

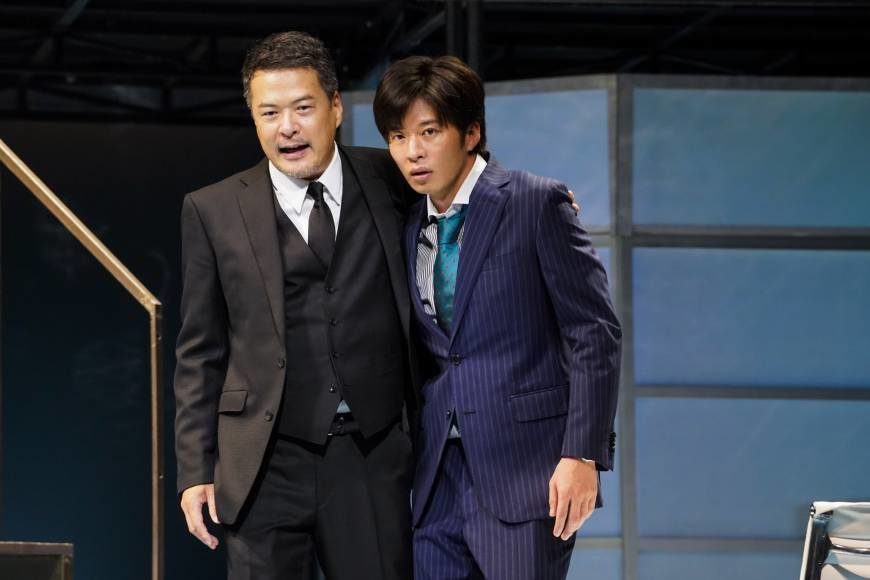

Set in the dog-eat-dog world of Hollywood’s film industry, the 1994 movie detailed the abusive relationship between a producer’s personal assistant, Guy (played here by Tanaka), and his cruel boss, Buddy Ackerman (played by Tetsushi Tanaka, but portrayed memorably in the original film by Kevin Spacey). Rounding out the main cast of the Japanese production is Maho Nonami in the role of Dawn, Guy’s love interest.

The story made its way to London’s West End in 2007 when English dramatist Michael Lesslie adapted it for the stage. And while the setting may be foreign, abuse of power in the workplace is all too familiar to audiences in Japan. Director Tetsuya Chiba, who also acts the role of studio chairman Cyrus Miles in the play, was keen to tell The Japan Times how he has revamped this pre-#MeToo drama for today’s audiences by taking a whole new approach to the plot.

“The movie was made nearly 25 years ago, so some scenes aren’t credible in today’s society,” he notes. “Such a blatantly violent boss wouldn’t be tolerated now, which is why I asked Tetsushi to play the role with a lighter touch in more of a passive-aggressive way.”

In contrast, Kei plays his Guy as one of the recognizably meek new recruits that flood this country’s corporations each spring. He’s unquestioningly obedient and desperate to please.

In the original film, scenes jumped between the past and present, “but we can’t really do that on stage,” Chiba says.

“Instead, to avoid it being sluggish, I have disassembled this three-hour play by creating acting spaces in several frames and presenting different scenes in them chronologically to ensure a speedy flow as the story unfolds,” he adds.

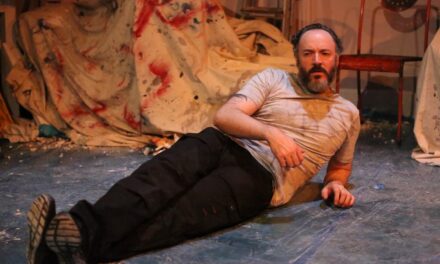

In practice, Chiba has fashioned a tunnel that opens like a corridor from behind into the company’s center-stage reception area, where meetings are held around a big table as the participants intriguingly play with wind-up toys.

Off to one side is Guy’s desk, with a kitchen behind and a spiral staircase leading up to Buddy’s office, from where he throws down documents and yells at his assistant, often demanding coffee. On the other side of the stage, meanwhile, another staircase leads to the inner sanctum of Dawn’s apartment furnished with a large sofa.

With this imaginative set and clever lighting changes that lead the audience’s line of sight to where the action is taking place, it’s remarkable how smoothly the director manages the play’s many scene changes—with a minimum of blackouts—and how speedily time passes in the process.

As to why he opted to stage this play, Chiba says the movie had a real impact on him, due to its surprising ending and Spacey’s portrayal of the monstrous Buddy.

“However, I’m more interested in depicting why ordinary people choose to make their living in such ultimately destructive ways,” he says. “I think that tragedy happens in many places and many organizations, so it isn’t specific to Hollywood.”

“In real life, in any company or society, people often cause discord and plot against each other to ensure their own survival — even in ways they don’t want to.”

He adds that in a society full of virtual objects and amid a flood of information, people are “more susceptible to losing their ability to judge a thing’s true value”

“As a result, I hope audiences stop thinking about what they can gain and instead stick firmly to things they know are right. In that way, this play is extremely relevant to life in Japan today,” he says.

Even closer to home, Chiba says Guy’s perplexity, Buddy’s cruelty and Dawn’s avarice are things he has seen represented in the creative world he personally inhabits.

“When Guy joins the company he is told there’s a huge difference between movies as a hobby or a business,” Chiba says. “It’s the same in the theater world, where people must often choose whether to walk all over a close friend or give up someone they love in order to advance their career. Of course, artists sometimes make nasty choices to achieve their goals.”

Furthermore, Chiba points out that there are no gold or silver medals or record times in the creative world. Instead, there’s “the sole criterion of sales, tickets or whatever, so many artists experience emotional turmoil between their artistic intentions and the demands of the business.”

In that sense, Chiba interprets the “sharks” in the title to refer to many people scrambling up the corporate ladder.

“Hence, I regard this play as a tragicomedy of broken people who have opted to compromise their creative and human values in order to pursue their self-interest.”

The director believes that Kei Tanaka’s fans, many of whom might be visiting a theater for the first time, could have doubts about the characters’ life decisions.

“I hope they reflect on where these decisions led them, because theater is a place where understanding is challenged, unlike the TV dramas they’re likely used to, which tend to spoon-feed passive viewers,” he adds.

The challenge that Chiba is delivering is made all the more complex when you realize that Buddy isn’t necessarily a villain, he’s an executive who needs to aggressively defend his position. And Dawn is just as aggressive — even more so as a woman who, as anyone who has followed the #MeToo story will know, is climbing a ladder steeped in patriarchal misogyny.

At least Tanaka’s detailed portrayal of Guy, with his bewildered facial expressions and adherence to the national pantomime of deep bows and corporate keigo (polite language), is sure to help the audience get through this nightmarish experience. So often in Hollywood, as in most companies, you’re on your own.

This article originally appeared in The Japan Times on September 4, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nobuko Tanaka.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.