Review: Jurrungu Ngan-ga, directed by Dalisa Pigram and Rachael Swain for Marrugeku

Jurrungu Ngan-ga, a Yawuru kinship concept meaning “straight talk”, is a throbbing protest about the violence experienced by Indigenous, racial, trans and queer Australia.

At its heart, a group of misfits share painful experiences in a way that reasserts their being-in-the-world, in this powerful performance from Broome-based dance company Marrugeku.

Directed by Dalisa Pigram and Rachael Swain, with Behrouz Bouchani and Omid Tofighian (author and translator, respectively, of No Friends but the Mountains) as cultural advisors, Jurrungu Ngan-ga weaves themes of violence traversing verbal, sexual, physical and psychological abuse, depicting scenes with slurs, humiliation, shame, and murder. In passing, rape culture, self-harm and suicide are also referenced.

The result is a whirlwind ride of bodies perpetually resisting.

Guards’ voices and murmurs from cells punctuate the space. The inmate (Chandler Connell) stays still and quiet. His sudden yell raises goosebumps. He repeats this yell, and it becomes the start of a dance, a corroboree-like stomping sequence, accessorized with a shimmy of the shoulders.

Now he screams “get out!” and whispers “I can’t breathe”. Invisible hands tie his own hands behind his back. A prison alarm interrupts and yellow, rectangular back lights shine bright.

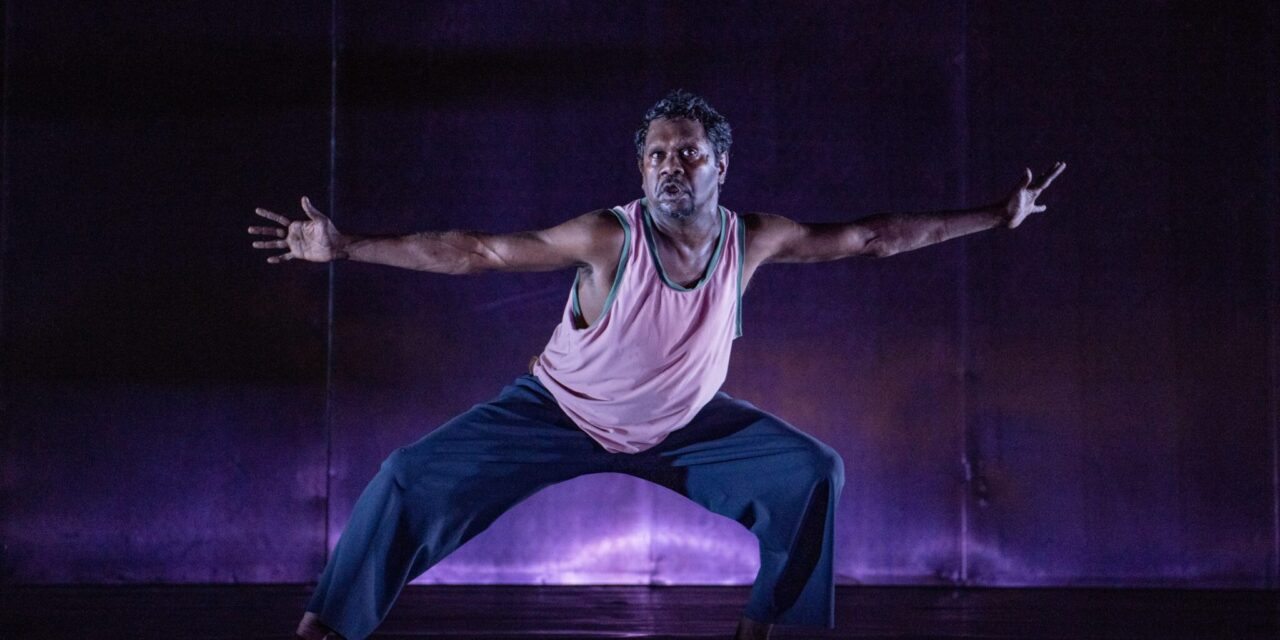

Movement soars through the space. Convulsions akin to orgasmic and spastic trembling; zombie-like expression where bodies collapse in on themselves. A classical pas de deuxrigorously executed by Miranda Wheen and Luke Currie-Richardson, but satirical so gestures are stunted and lines are clunky. Sinewy traditional Filipino dance reminiscent of Singkil. A low and fierce Torres Strait Islander warrior-like dance led by Czack (Ses) Bero. Joyful Middle-Eastern dabke folk dance. Awkward drunken Australian pub breaks.

Jurrungu Ngan ga draws influences from a global dance history. Abby Murray.

An explosive rendition of Childish Gambino’s This is America substitutes America for Australia: hypersexualized fetishizing of the group’s oppression. A costume morphs into a camp Captain Cook or a fabulous Arthur Phillip. Like Donald Glover’s nightmare, the music, dance and lighting are all perversely enjoyable.

Krump – a fierce energy simulating a body in battle – explodes through the bodies of these now-aggressive human beings, forcing onlookers to confront and resist the racist stereotype of angry black and brown people.

The whole cast passionately convey their resilience, but it is Benji Ra’s presence that resonates.

In one scene, she gasps her own soundscape. She travels across stage like a doll, and through words that sexually and racially exoticize her. Her body and her words deteriorate into a dog growling, barking. Then back to a robotic voice, she playfully stutters “some of my best friends are delicious MILFs”. She smiles, allowing the audience to giggle at this with her – but her self-objectification is laid bare, ripe for exploitation.

Benji Ra (right) has a presence that resonates. Abby Murray.

Elsewhere, she recounts the death of a friend, Yolanda Jourdan, “the woman with lemon-blonde hair”.

This story elicits a long list of names with similar stories.

A person shot in Northern Territory.

…driven 350km in extreme heat in the Kimberley.

…found dead in his cell with four broken ribs.

…chased by NSW police officers before being impaled on a fence right here in Redfern.

…who set himself on fire in Nauru prison.

How do we embody fear?

It would be easy to witness the suffering bravely portrayed by the cast as yet another display of Black trauma porn, relying on shock value rather than a coherent concept.

In turn, it would be easy for me as a white spectator to report experiencing feelings I can readily dismiss.

But the audience in Jurrungu Ngan-ga are never just spectators. The audience vocalises our response by snapping our fingers, stomping the floor and yelling words of encouragement more common at a hiphop cipher or a vogue ball.

The audience are not just silent spectators. Abby Murray.

What transpires, then, is a radically provocative piece of dance theatre where audiences learn in emotive detail about systems of power and control.

We learn of the disproportionate incarceration of Aboriginal people – including children – and their deaths in custody. Of the continued imprisonment of refugees seeking asylum in Australia pushing many to self-harm or suicide. We learn of media misrepresentation and lies, harmful tropes and oppressive policies that sustain white supremacy in this country.

At times, the audience is cast as complicit. At other times, we are allies. No-one remains a victim. Every person on stage speaks back to violence. Spectators leave after being literally encouraged to act.

The most arresting resource of Swain and Pigram’s dance theatre work is speech. Towards the end, Connell speaks with rawness that is unmistakably real, even if his words are someone else’s.

“Jugun” he explains, “is when you lay between two fires… I’m Koori. What do you see?”

He instructs us to close our eyes and speaks in Language. He returns to English: “the most important thing [is] to live in this moment and breathe.”

Jurrungu Ngan-ga asks “how do we embody fear?”.

“We are a nation of jailers,” Patrick Dodson says. “We lock up that which we fear”. As Lilla Watson puts it, “your liberation is bound up with mine”.

There is more jurrungu ngan-ga – straight talk – to be done about our nation of jailers, but this piece propels an urgent call.

Jurrungu Ngan-ga played at Carriageworks, Sydney. Season closed.

This article was originally by The Conversation on January 30, 2022, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, please click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kate Maguire-Rosier.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.