Consciousness, cognition, and perception have fascinated Jisun Kim and The House of Sorrow is a mind-mending Möbius strip of a show, blending Buddhist philosophy with video game streaming.

Where are your thoughts? In your mind?

Then where is your mind? In your brain?

Then are your thoughts in your brain cells?

If thoughts are a thing, a tangible object like brain cells, then could you transform them into something else?

The House of Sorrow is a narrative puzzle box that focuses on a man called Min who was looking for a way to rid himself of his pain. Min gave Jisun Kim a game he created that is now played onstage by a gamer. The audience watches the gamer’s livestream. Needless to say the game itself and the show are labyrinthine, full of secrets and mysteries, like a journey into the mind itself.

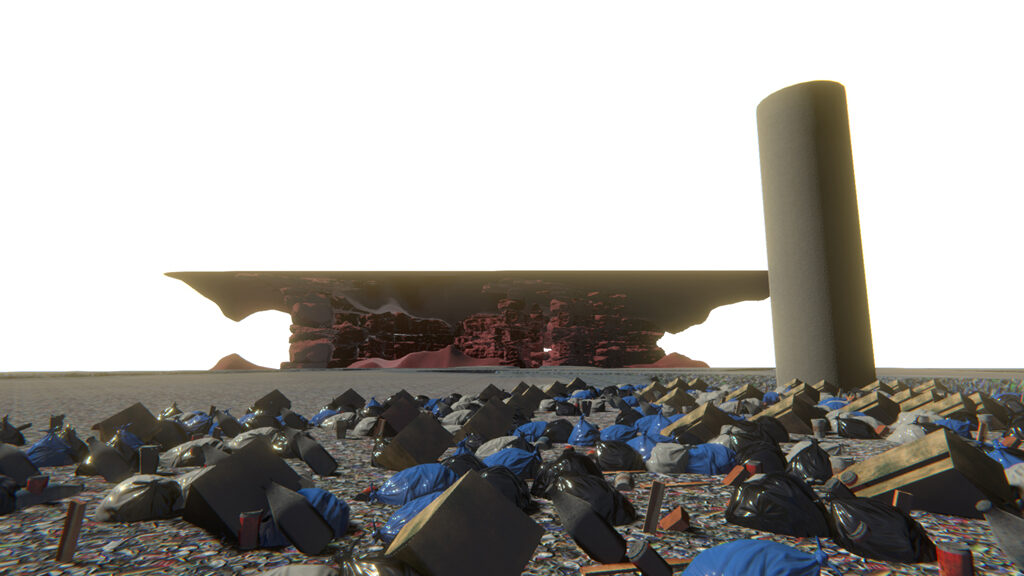

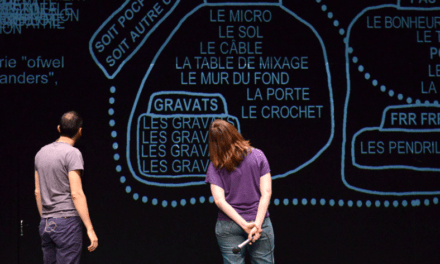

The virtual world of the game is at once simplistic in aesthetic yet densely complex in its structure. Black garbage bags litter the vibrant, saturated landscapes and interacting with them reveals photos of Min’s encounters with ancient South American rituals and healing practices. Golden ornaments and East Asian artworks fill a museum that turns into a jungle that leads into a 2D cubist-style memory palace. It feels like a virtual collage of the real and the representational. Avatars fill the museum-like overly realistic yet unmoving mannequins and glitching animals appear unnaturally in the world to confront us with philosophical musings. A motif of a simple wooden house recurs, referring to Buddha’s quote in the museum: ‘Builder of the house of sorrow, you will not build the house again’. Yet there are many houses in this game, or is the game itself the house of sorrow? Originally Min’s game required the player to spend several days simply exploring and existing in the virtual space in order to progress. Fortunately, Kim’s modifications means that’s no longer necessary but nevertheless it’s clear there are no obstacles to overcome here but a world to experience.

The House of Sorrow by Jisun Kim, 2020. Photo Credit: Bea Borgers

Kim continually circles back to the problems of consciousness. How can a brain understand the brain? How can you restructure your way of thinking? For Min the answer seems to lie in the game world he created for himself. Far from being a simplistic retreat from the ‘real’ world, the game provokes a profound meditation on the nature of consciousness. It’s revealed Kim met Min in South America where he was seeking indigenous healing methods and she heard about the tale of El Dorado. In a city of gold the people would craft and work the metal into wonderful objects before throwing them back into the lake, like Tibetan monks making intricate mandalas in the knowledge that they will be destroyed. Inevitable destruction doesn’t negate the value and appreciation imbued by the creative process – therein lies the heart of The House of Sorrow. Once the players acquire hands and a gun, all of a sudden it becomes an existential first-person-shooter in which they can destroy one world to reveal a new one underneath it – no longer passive observers of the world but active creators and destroyers. There are no objectives, no final challenge to overcome because there is no real end to anything. The only obstacle is the house of sorrow you’ve built for yourself and the only way to escape is to end the cycle of suffering. Simple, that should only take a few lifetimes.

As soon as the show ends it’s tempting to see it again, with a greater appreciation of the intricate macro-structure to the piece. By the end, we’re left with such an extensive reading list that would undoubtedly enrich a second viewing. However, each iteration of The House of Sorrow uses a different gamer leading to a fundamentally different encounter with this virtual reality – a perfect analogy for the cycle of reincarnation. Ultimately this is a show about mediation and the limits of our perception: we can only experience Min’s experience second (or third) hand via Kim and the gamer, right now you’re experiencing it fourth-hand via this article. Is one more ‘real’ than the other? Does the retelling diminish or enrich it?

No matter what, The House of Sorrow manages to combine ancient mind-bending philosophy from around the world with modern technology that contains untold layers and undiscovered secrets. There’s even a version of it available in Minecraft to add yet more dimensions to this intricate piece. Playing the game helped Min understand his own pain and brain. Watching the show helped me understand mine.

This article appeared on E-tcetera.be on September 9, 2020, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Liam Rees.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.