The Russian Case: History, politics and eternal values

Spring, with all of its uncertain promise, is a time of awakening. In Moscow, theatres are gradually waking from their enforced hibernation. The permitted number of spectators in the theatre auditorium is gradually increasing. Masks and sanitisers have become the theatre’s new companions, along with binoculars. Melpomene, the muse of tragedy, comes back to life. For those of us who still dream of travelling to the theater, The Golden Mask Festival offers the opportunity to immerse ourselves in modern-day Russian theatre. This year’s Russian program was held online and introduced foreign audiences to interesting examples of Russian theatre. Reinterpretations of classics and experiments with form, performance-collages and chamber productions, music and choreography, surrealism and harsh realism – Russian theater has a colorful palette. It may be in the form of recordings, sometimes of very mediocre quality, but the magic of theatre once again confirmed its ability to demolish borders, crises, anxieties and despair, which we ourselves all too often hide.

Kirill Serebrennikov, Konstantin Bogomolov, Andrey Moguchy, Boris Yukhananov, Dmitry Krymov, Timofey Kulyabin and many other directors reflect, invent, dream, argue, resent, provoke and ultimately look for their own ways of understanding the world and entering the audience’s souls and minds. At a time when we are all more acutely aware of the fragility of the world and our own loneliness, the theatre is rethinking itself as a means of communication and dialogue. We can often feel, or at the very least, begin to soak up the unspeakable inside the theatrical realm.

If the video version castrates the performance, depriving it of the “here and now” that Konstantin Stanislavsky spoke about, then the retelling of the video version leaves only a vague, subjective outline of the performance. The video recording is the first acquaintance with the performance, the source of the first impression, the prelude if you will. And yet, this first impression is a harbinger of an early and somewhat hopeful meeting. When we once again remove our masks, the magnificent five below become performances. They are destination points inspiring a theatrical tour of Russia.

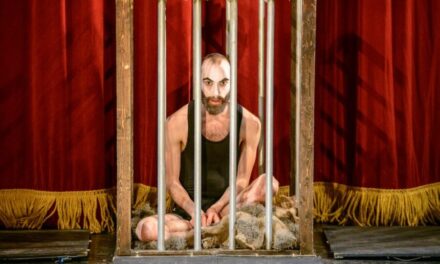

BORIS

BORIS is based on on the historic drama “Boris Godunov” by Alexander Pushkin. This is a project by Dmitry Krymov, producer Leonid Roberman and The Museum of Moscow. Dmitry Krymov describes the howling performance as follows: “Pushkin’s Boris Godunov is the most dangerous thing. Highly unconventional. Like a Picasso painting, painted before the peredvizhniki (“The Wanderers,” a group of Russian artists protesting academic restrictions) and academicians. Pushkin wrote this hooliganism two hundred years ago. We are used to it, in as much as one gets used to a broken window. It is no longer dangerous, the fragments are no longer cut and the wind no longer rushes upon it. You need to look for sharpness elsewhere. Maybe we should break it again.” The director transfers Pushkin’s historical plot about the burden of power to the circumstances of modern Russian political reality. This is not a performance pamphlet, but the parallels with today are obvious and audible. The circumstances and morals from past centuries rhyme with modernity and the distance from the audience is reduced to frightening intimacy and deafening truth.

DOSTOEVSKY`S DEMONS

The play at Moscow Theatre is based upon the novel by Fyodor Dostoevsky, directed by Konstantin Bogomolov. The director formulates his production as follows: Demons is both a detective story and a melodrama. Demons are also metaphorical peals of Russian public life and its myriad harsh realities, which remain unchanged from century to century. Demons is more so about the study of boundaries and limits; the imperceptible deterioration of our long-held values; the mental crisis of civilization, the mess of man and humanism. After all, Demons silently screams an ode to the end of time – the waning of hope, meaning and the penetrable energy of life versus the unhinged reign of death.” In this complex play, videography and memes from actual Russian reality are intertwined with the political circumstances of Dostoevsky’s novel. A cross-section of modern Russian life with its recognizable characters and archetypes is packed into a gloomy macabre, where there is not a single ray of light. The director plays one of the key roles in the performance and masterfully plays with the audience’s perception, manipulating the audience’s emotions. This is a moral experiment that leaves the viewer alone with their own inner demons.

GORBACHEV

The play by Alvis Hermanis at the Moscow Theatre of Nations is not about politics, but about love. The director and author of the text says about his performance: “If there is one person in the twentieth century who has greatly influenced the lives of hundreds of millions, it is Gorbachev,” says Hermanis.

“It was he who redrew the map of all of Eurasia; he found the key to the prison in which we were immured, taking a step towards glasnost (increased government transparency). Personally, I used to think that the USSR collapsed due to economic reasons. Now I am sure it was due to just one person. And the purpose of the performance is to understand the specific qualities of this individual, the soulful idiosyncracies that led to the fact that he became the grain of sand that formed a blackened pearl in the political machine.”

This is not a biopic, but an apocrypha. It is a sentimental, touching, strong and pure story that deals with two people and their love for the background of the era’s change. Two bright performances by Yevgeny Mironov and Chulpan Khamatova captivate with their energy, thoroughness, detail and voices. It is an amazing example of reincarnation and intimate intonation, informing us that love is stronger than death.

Gorbachev

THE MAN WITH NO NAME

The Moscow Gogol Center performance based on the play by Valery Pecheykin is a collaborative work by Pyotr Aidu, KirillSerebrennikov, Nikita Kukushkin and Alexander Barmenkov. The Man without a Name tells the journey of a soul that finds itself on the verge of death. He is Vladimir Odoevsky is the “Russian Faust”, and a novelist, philosopher, public figure and mystic. Being a contemporary of Pushkin, Odoyevsky was undeservedly forgotten by subsequent generations. Especially for this performance, the composer Peter Aidu created a unique instrument, a pan-harmonic consisting of ten reassembled mechanical pianos. This is a rare theatrical experiment in which music, words, visual images and metaphors penetrate each other and arouse the audience’s imagination. It is both an energetic and playful composition, full of deep psychology and theatrical alchemy. Loneliness and incomprehensibility, being lost in the flow and life and discovering new worlds within oneself whilst expanding the limits of human knowledge – all these questions pulsate in the performance, making the hearts of the audience beat faster.

A TALE OF THE LAST ANGEL

In the performance by Andrey Moguchy based on the works by Roman Mikhailov and Alexey Samoryadov at the Moscow Theatre of Nations, Russian folklore is intricately intertwined with the atmosphere of the nineties. As the poet Alexander Pushkin said: “Tale of sense, if not of truth!”

It provides food for thought to honest young people. Images that we unconsciously absorbed in childhood, suddenly take on new frightening meanings in the play. We see scary fairy tales and scary realities, such is a fork driven into the plump flesh of human destiny. Andrey Moguchy, while meditating upon the play said:

“In the stories of Roman Mikhailov there is a charge of authenticity and purity. His characters are naive, strange people, ‘people of secrets.’ They live in the same world as us, but they have a special vision – to see and feel the world differently, holistically, openly and truthfully. They can walk on invisible paths between reality and dreams, talk to the sky, hear the voices of grass and wind. And thanks to this ability to be one with nature, to be truly like children, they can change prick the bubble of reality in order that they may save the world with their sincerity and love.”

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Emiliia Dementsova.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.