The nominations for this year’s Mahindra Excellence in Theatre Awards (META) were formally announced on February 11, after a few days of speculation on the proverbial grapevine. The ten productions in contention for as many as a dozen awards will vie for jury attention at the META festival to be held in March at various locations in the capital, including de rigueur venues like the Kamani and Shri Ram Centre auditoriums. Now in its 14th year, the annual event is both a noteworthy showcase of the best Indian theatre ostensibly has to offer and a contentious barometer for excellence that is never quite easy to assess. As might be the case this year, the selections attract awe and angst in equal measure. This is perhaps to be expected in a performing arts ecosystem that is far from monolithic and occupies a colorful spectrum of cultures, sensibilities and human experiences.

Striving for perfection

It must be said that the belief that excellence is essentially subjective flies in the face of a festival that zealously guards the idea as a prized concept. However, subjectivity shouldn’t become the crutch by which to perpetuate the rum notion that there are no rotten apples in a crate full of seasonal fruits, even if comparing apples to oranges is not quite your thing. The META selection committee (of which this writer was a member this year) often consists of people from different walks of life, who bring their own gendered lens and personal prisms to the process.

Yet, widely differing ideologies and sensibilities can temper each other, and give rise to a situation whereby different kinds of excellence might bubble to the surface, which META, in its well-intentioned efforts, attempts to gather into its fold. These are utopian ideas that might never actually be borne out in practice, which is why it is important to view META not as the last word for anything, but as indicative of how a huge but amorphous and unorganized “industry” continues to strive for artistry and perfection, despite all the operational and fiscal constraints that are now a given.

Politics and diversity

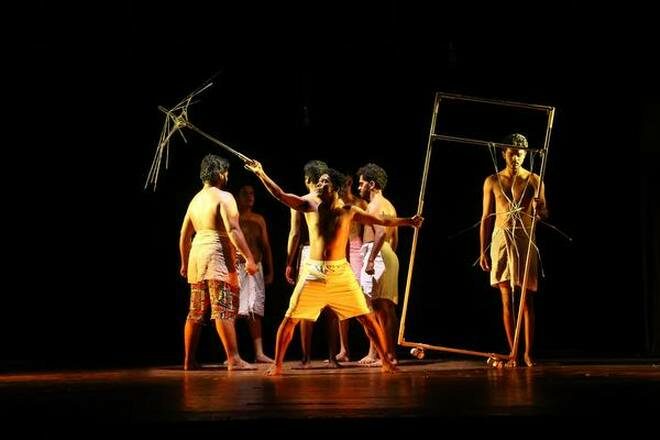

Even if the optics of representation, whether it’s in terms of gender, region or language, was not a premeditated consideration for the selections, this year’s contenders represent a particularly diverse set. On one hand, you have Atul Kumar’s Detective 9-2-11, a comic caper that skirts the edges of mainstream entertainment, and on the other, there is the unrelenting subaltern ethos of Bineesh K’s production of N Prabhakaran’s epic play Pulijanmam. Plays in seven languages from eight states have made the cut. This includes the first-ever Gujarati play at the METAs—a comic adaptation of Dharamvir Bharati’s Andha Yug that is at once irreverent and faithful to the original. As a testament to its enduring appeal, Bharati’s 1954 epic in verse, once dismissed as a radio play, is also represented by a second play at this year’s play-offs—Joy Maisnam’s version from Manipur, performed in Hindi.

Three plays have been directed by women. Dhwani Vij’s Bhagi Hui Ladkiyan is a documentary excursion into the lives of Muslim girls in Delhi’s teeming Nizamuddin Basti, while Maya Krishna Rao’s Loose Woman is a look at the manifestations of the eponymous entity around us, which is as much a function of a societal gaze as it might be of dubiously declared character. Swati Dubey’s Agarbatti is a production from Jabalpur’s Samagam Rangmandal, which deals with the dramatized attempts at social rehabilitation by the widows of the Behmai massacre. It is a world altogether different from the sleepy hamlet of Koumarane Valavane’s Chandala, Impure in which a caste-crossed version of Romeo and Juliet plays out against the backdrop of mainstream Tamil cinema’s cultural imprint.

Agarbatti’s upper-caste widows or the women of Achyut Kumar’s Kola, a Kannada adaptation of Mahesh Elkunchwar’s Magna Talyakathi, grapple with a privilege that they’re born into but which doesn’t really empower them. Including Arun Lal’s rousing Chillara Samaram (The Strike Of The Common Man) and the aforementioned Pulijanmam, both from Kerala, it is culturally significant that the politics of caste informs at least six of the plays in this year’s list.

Once again, this is just the tip of the iceberg. Beyond lies a universe in which the status quo, dated but thriving, grapples with new voices and an emerging zeitgeist. It is an unwieldy equilibrium that seems poised at the cusp of a transition that might lead to great things.

This article appeared in The Hindu on February 12, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vikram Phukan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.