Tokyo was bathed in warm sunshine in the run-up to 2016, and when Takehiro Hira meets me at a rehearsal studio his smile is beaming just as brightly — while in his arms he’s carrying a box of mikan (mandarin oranges) to share with the rest of the team as they prepare for this month’s rerun of Ai Nagai’s acclaimed Kaku Onna (“A Writing Woman”).

The award-winning play from 2006, which Nagai is directing, is a moving, multilayered work inspired by one of Japan’s most important female writers, Natsuko Higuchi. Though she died at the age of 24 in 1896, Higuchi (who used the pen name Ichiyo Higuchi) achieved such standing in her short life that her face now graces the ¥5,000 banknote.

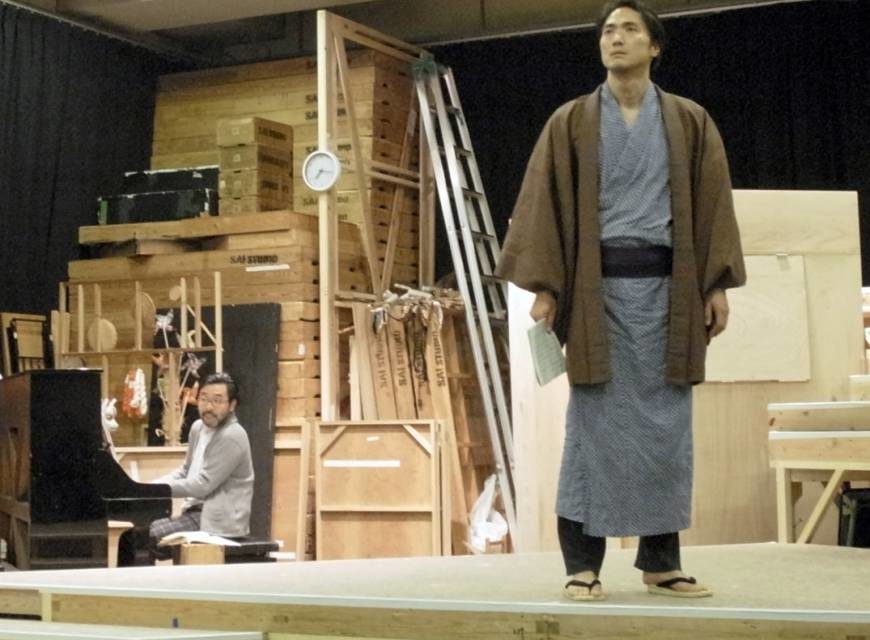

In this production at Setagaya Public Theatre, 41-year-old Hira plays Tosui Nakarai (1861-1926), a real-life journalist who wrote serialized fiction for a newspaper and became the writing coach and career adviser to Higuchi (played by Haru Kuroki) — and maybe, or maybe not, her lover, too.

Born into a middle-class Tokyo family shortly after the dawn of the modernizing Meiji Era in 1868, Higuchi began studying tanka and classical poetry when she was 14. Then her father’s business failed and he died deep in debt, leaving the family impoverished. It was after they moved to a cheaper place near the notorious Yoshiwara red-light district that Higuchi turned her literary skills to writing short stories — many concerned with helping the downtrodden and empowering Japanese women.

Among these was her masterpiece, Takekurabe (“Growing Up”), about a young prostitute who falls deeply in love. The book made her famous, but she died of tuberculosis just 14 months after it was published.

Reviewing the poignant story of Kaku Onna as we eat mikan, Hira says, “The relationship between Higuchi and Nakarai is the play’s most interesting aspect — though whether there was just affection between them or real love, Nagai leaves audiences to decide.

“But I personally think they were just platonic friends,” he adds, “hence they could maintain their relationship even after becoming victims of widespread gossip.

“Yet in acting the part of Nakarai, even though he is described as a gentle intellectual, I’d rather suggest more of a man-about-town sort.”

Centered largely around this pair’s conversations, even though Kaku Onna conveys a powerful sense of the suffocating social restrictions imposed back then on even professional women, the play sparkles with Higuchi’s genius in the genre of romantic realism weaving together her longing for Nakarai amid the hard grind of daily life.

For Hira, though, this isn’t at all how he saw his life playing out after his famous parents, the actors Mikijiro Hira and Yoshiko Sakuma, divorced and he and his twin sister, then small children, went to live with their mother. In fact, he says, “I never dreamed of following in my parents’ footsteps,” so when he was 15 he moved to a high school in the United States, where nobody knew about his background.

After graduating with a degree in applied mathematics — and “really enjoying my life in America,” he mentions with a laugh — Hira returned to Japan at age 25 and started work at an investment company. That, however, wasn’t destined to last.

“I’d always loved creative writing and I always wanted to do a creative job, yet I persisted in refusing to follow my parents into acting,” he says. “That was until I was 27 when I realized that was what I really wanted to do.”

Nowadays, Hira is one of his generation’s most in-demand stars in Japan — and he’s even shared a stage with both his parents on several occasions.

In Kaku Onna, though, his nuanced relationship with the gifted and driven writer Higuchi leaves me wondering what this eligible bachelor’s own idea of an ideal woman is.

“As my mother has always thrown herself into her work, I don’t have the image of a woman who stays at home,” he replies. “So I hope my future wife will be independently working in her own field.”

Generally speaking, however, he says he wonders “if Japanese women really want to be socially equal to men.” For instance, when a female American friend was visiting and they went for dinner, he says he offered to pay as that’s the custom in Japan — but she told him “not to treat her like a little girl,” and insisted they split the bill as friends in the United States normally do.

“If Japanese women aren’t ready to accept a truly equal gender system, they will have to accept living under men’s umbrella and nothing will change,” Hira says. “But if they work equally in society and are independent, then society will treat men and women equally.”

That’s all very well in theory, but just recently the government slashed its target of having women filling 30 percent of management roles by 2020 to a piffling 7 to 15 percent.

Clearly, Higuchi’s battle to improve the standing of women in Japanese society is still a very relevant issue.

This article was first published in The Japan Times. Reposted with permission of the author. Read the original article here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Nobuko Tanaka.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.