Over two decades ago at the annual Purim spiel (a satirical play at the Jewish spring festival) of Los Angeles’ then only gay synagogue, I was cast to portray Tevye’s gay son alongside a bearded gay man attired in a wedding dress acting the part of Fiddler on the Roof’s closeted Lesbian daughter. Hardly a memorable performance by all who witnessed the spoof, it brought to the surface some of the challenges, Thespian and otherwise, that enable one to keep one’s gender identity straight, in a manner of speaking, on and off the stage.

Gender-bending has been with humans ever since man put on a kimono / kilt / toga / and women pants, etc. and struck a heroic pose before a crowd or a mirror. Historically, gender-bending was a tool in character development. When the respective curtain went down, and the greasepaint came off, everyone went back to “normal”: guys will be guys, and girls, girls.

By design, nothing’s clear-cut at Japan’s Takarazuka Revue, arguably one of the world’s largest all-female musical theatre groups. The women who portray male roles in the Revue’s repertoire must maintain a semblance of “maleness” off-stage as well, the “off” boundaries being far away from the theatre environs. Because of the company’s strict social code, “male” stage personae are skillfully flaunted and deftly tossed as golden apples for avid fanbase by the Revue’s publicity machine. Even kabuki onnagata, males who portray female roles, take off their “onstage” gender with their greasepaint.

But it’s not just the gender-bending onstage that makes Takarazuka so compelling a study. It’s its capacity to sell a secret, forbidden dream to its audiences and then compel them to talk openly about it!

The Takarazuka Revue was the brainchild of the visionary promoter industrialist entrepreneur Kobayashi Ichizo, who established its predecessor in 1913 to attract tourists to Takarazuka (near Kobe) via his Hankyu railway and enjoy his onsen (hot springs resort). His enterprise was also later exported to Tokyo and grew as he added their shopping in his Hankyu department stores to the mix. This legendary pitchman created a “unique selling proposition” (a classic modern advertising term) by grafting wholesome family values on “high-concept” (lots of sequins and big production numbers) sexy-ish entertainment and put his money where his … er … balls were.

Kobayashi hit upon his target market dead center: the growing number of middle-class matrons (and their junior matron daughters) who found themselves with discretionary income and time to spare once their desk-bound husbands-by-arranged-marriage were at work and the kids were at school. A great marketing strategist, he somehow knew exactly what Japanese women wanted and set out to sell it to them on his terms. To this day millions of women are hooked enough to venture beyond their everyday comfort zones into the realms of forbidden. (Dare I say it? My open palm is covering my mouth as I do) – homosexual-portrayals of heterosexual romance.

Kobayashi hit upon his target market dead center: the growing number of middle-class matrons (and their junior matron daughters) who found themselves with discretionary income and time to spare once their desk-bound husbands-by-arranged-marriage were at work and the kids were at school. A great marketing strategist, he somehow knew exactly what Japanese women wanted and set out to sell it to them on his terms. To this day millions of women are hooked enough to venture beyond their everyday comfort zones into the realms of forbidden. (Dare I say it? My open palm is covering my mouth as I do) – homosexual-portrayals of heterosexual romance.

We’re not talking sex the act, but sex, the identity. In reality, a woman need not perceive of her lover as a man or woman to love her.

The 90+ year old Takarazuka “phenomenon” can be observed from near and far: attending performances and cruising fan-ter-prise shops, reading official and unofficial Web sites and published scholarship, and viewing films including a documentary and narrative releases such as the 1957 Hollywood production of Michner’s Sayonara. In the past few years, there’s a growing amount of it in English language as well. Three distinct but related areas of the “phenomenon” are apparent: the school, the performance on stage, the life off stage.

Studying Takarazuka takes one to the borders of the sexual frontier to witness the moment of dreamy climax, even beyond invisible “fourth wall” of the stage at the moment of penetration. It amplifies the heart’s deepest secrets …“Yes, I am in love with her because she is a better man than my husband.” (A female fan’s confession with open palm covering her mouth.) It begs the universal question, “When is a woman enough “like” a “man” to portray a man making love to a woman portraying a “woman”? It also begs the question, Who’s guarding these borders and to what end?

20th Century Marketing Oiemoto

Kobayashi-san was a pure Japanese Übermensch, a self-proclaimed Taisho-era bunkajin, aesthete, with oiemoto (grandmaster of an artistic tradition) tendencies. His aesthetic oeuvre was inspired by domestic Kabuki theatre and the ukiyo-e (woodblock print) world of Geisha culture. To his credit, scholar Makiko Yamanashi adds that he intended to establish a new theatre institution in protest against the ‘Geisha’ world, one that ultimately established a new status for female performers but still denied the majority of female theatre professionals an unqualified legitimacy.

He was able to read the handwriting on the shoji-paneled wall: Japan was barreling away from, if not sucked out of, its isolationist past by the insatiable desires of all things other-worldly (read: “Western”) and exhibited a sense of bravado befitting his country’s expansionist, capitalist ambitions.

He was in good company with the likes of his predecessor the American Buffalo Bill Cody whose late 19th Century Wild West Shows, complete with whole tribes of war-painted Indians, galloping herds of buffalo and horses and wagons, were the toast of Victorian England and the continent for decades. Cody understood the allure of gender bending in his employment and promotion of sharp shooting cowgirl Annie Oakley. But, while Oakley was trying for love to “get a man with a gun,” Kobayashi’s femme fatales aim their weapon (in this case, their “gaze”) at the hearts of members of their own sex on stage and, most especially, in the audience. The latter, if given the chance, with a gun in hand, would more likely take revenge on their husbands for staying out late at night with office colleagues.

Kobayashi could be counted among the virtual relatives of Walt Disney, lord-god of the many lands throughout the world that bear his name. Unlike Disneyland, where “when you wish upon a star, your dreams really do come true!” Kobayashi made his fortune by keeping those dreams aloft. Both made their fortunes by creating singing and dancing characters with flat personalities, whose heavily mascara-ed eyes could deliver a mesmerizing, laser-like “gaze” that can ignite a sense of dreamy happiness into hearts of every single member of the audience at once.

He was also very much in the lineage of Russell Market and S.L. Roxy Rothafel, consummate showmen who grafted good old Mid-West American family values onto a European follies-like show to create New York City’s high kicking, show-stopping Radio City Music Hall Rockettes. To this day Rockefeller Center boasts that “every girl dreams” of joining the infamous chorus line that catapulted the Big Apple’s into the heights of the streamlined Modern world. Kobayashi also made sex, art and the city inseparable.

By extension, his fraternity also could include bunny wrangler Hugh Hefner who created the Playboy enterprise in 1953. Hef formally defined and captivated a very large market of American men, especially those of college-age, and set out to tantalize and serve, but not completely satisfy, it. His objectification, stylization, and commodification of women project a “Huck Finn innocence encountering enthusiastic lewdness of American advertising and entertainment”[i].

TA-TAAAAA!!!!!

The Takarazuka Review content is more suited to therapeutic psycho- / socio-drama sweetened with a squirt of pop culture. All Takarazuka Revue performances run along a precise formula: Girls in their late teens to early 30s portray romantic heterosexual couples in tightly produced melodramas whose plots are flooded with longing for love. This immediately sets Takarazuka off from the average bawdy drag show where innuendo and out the other are chapter and verse that maximize comedic impact. Every gesture – especially those that would mark gender elements — on the Takarazuka stage and off, is well rehearsed and monitored with calculated precision: a tip of the hat, a twist of a tie

Each stage show is formulaic: the first act is usually based upon East Asian classics or European and American Broadway hits. French and Austrian pieces are very popular as has been Oklahoma, Singing in the Rain, My Fair Lady and Uestosaido Monogatari[ii] (Westside Story), among others.

The Takarazuka dramaturgy also has inspired, as well as been inspired, by manga (Japanese comics). Tezuka Osamu, the founder of the “cartoon” genre, lived near the home theatre. The company’s extremely popular Rose of Versailles piece, inversely, turned the trend around by being inspired by a manga. The in-house playwrights penned many original pieces, including unabashed propagandistic works that were performed in Japan’s colonies in the early-mid 20th Century. New material must be constantly written to keep the loyal fan-base filling over two million seats a year, combined in the two (Takarazuka and Tokyo) resident theatres, at 3000 per full-house performances, .

With a few exceptions, a performance will also include a second act, which is more a variety show of music, dance and connecting narrative based upon some fantasy theme, such as Mediterranean life morphing into that of outer space. The grand finale presents over 60 performers (dressed gender-appropriately) dolled up in sequins, feathers, top hat and tails parading down the stage’s grand staircase under the flickering lights of a mirrored disco ball. Wide gestures, and music that reaches a crescendo at the height of some purported dramatic climax, tug on the emotions like a Stephen Spielberg movie.

As the applause dies down and the house lights go up, audience members are free to transfer their hyped up need for climax by eating in Revue-brand cafes and, most importantly, shopping in the various Takarazuka-themed boutiques surrounding the theatre [iii] and throughout the city. Faces of Top Stars, still dressed in second-gender-appropriate fashion are on everything. Those big eyes, those “manly” gestures. Oh baby. Oh baby. Gimmme!

After watching a performance by the Takarazuka Revue at the mother-ship (Takarazuka Grand Theatre in Takarazuka), I had a feeling that it was Japan’s revenge for D’Oyly Carte’s production of Gilbert & Sullivan’s Mikado, the latter with its squinty-eyed sailors and foolish courtiers. Takarazuka’s low-concept production values pale in comparison to even ho-hum quality Las Vegas lounge acts. Think: small community college theatre with a big budget. However, I feel that Takarazuka has succeeded where most performing arts productions have failed by profoundly drawing the audience deeply into the action from even the cheap seats.

Every Girl’s Dream

The company numbers about 400 “Takarasiennes,” all graduates of the Revue’s two-year song-dance-act-march-bow-sweep-dust-polish-military-monastic school. About 50 girls in their mid- to late teens out of the thousand or so who apply for admission every year are selected through a beauty-contest-like application process by a primarily all-male committee to train before being allocated to serve in one of the five troupes. Takarazuka assures nervous mothers and fathers that their daughters’ virginity (or at least wholesomeness) will be protected by the “Violet Code,” a type of loco parentis that guarantees for the length of her affiliation. According to statistics, being a Takarasienne improves a young woman’s chances of marriage, no matter what her stage role. They usually “retire” before they reach Christmas Cupcake” age (25), but some of the members have performed even into their 80s, such as Kasugano Yachiyo.

Early in their training, the young women are assigned a “second” gender, selected mostly by physical attributes. Some will portray boys/men and other, girls/women for the duration of their professional careers with the company. It is these “male” performers who are touted as “Top Stars” and learn to deploy a special “gaze” that is aimed at, or so it seems, every single member of the audience.

It amounts to over three hours of foreplay with an intermission. There can be two SRO performances a day.

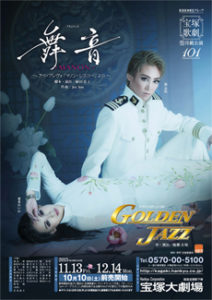

Caleb Hunt, Private Eye. Takarazuka RevueCompany. Photo credit http://kageki.hankyu.co.jp/english/revue/2016/caleb_hunt/gallery.html

Fun House Mirrors

Anthropologist Jennifer Robertson dedicated a decade to dissecting Takarazuka’s mystique and unraveling the “Violet Code” that shrouds its secrets. Her exceptional book, Takarazuka: Sexual Politics and Popular Culture in Modern Japan[iv], shows how, to this day, the late Kobayashi’s samurai-code serious successors manage the complex enterprise with goose-step precision, and how they contort and control the moga (modern girl) all in the name of “Cleanliness, Purity and Grace,” the Takarazuka motto.

Takarazuka promotes proper heterosexual behavior through homosexual divertissement and, at the same time, insists that its cast members are virtuous with a capital “V.” In the molding of the otokoyaku, the “male” performers, Takarazuka trains a girl who is androgynous enough to “become” a man off stage who can play a male character on stage. The “male” performers and musumeyaku (literally: daughter role) “female” performers, are hardly ever found outside the “…”

And we’re not talking about one of those sugar-daddy relationships between older men and younger women (the male / daughter complex). It’s more that the “girl” is presented to be inexperienced, naive, fresh, virginal to the “man’s” well-clarified, impulsive desire.

Otokoyaku are hyped informal portraits wearing, for example, white tie and tails or kimono and hakama. In the same publicity portraits, musumeyaku look like the girl-next-door dressed as a bridesmaid or conservative Geisha. When they appear before the scores of fans at the stage door who bring lavish gifts to bestow upon their heartthrob, it’s high fashion short hair for “him” and more “feminized” attire for “her.” During their school days, like most Japanese, they wear their uniform with spit and polish.

This isn’t gender bending, rather gender yoga, in both the Japanese and Sanskrit sense. Unlike drag shows full of innuendo, were shows where forbidden sex is the point, in Takarazuka land sex is forbidden. Rather, Takarazuka sells 100% pure puffy cloud-like romantic dreams – the song and dance, the refreshments in the lobby, the entire contents of the malls full of souvenir shops, the pavement of the streets and sidewalks, the fan magazines and websites, all a dream and everyone knows it. It’s not about satisfaction, rather, to see how much one can consume before it’s too much.

The musumeyaku off stage and on is more a prop of the otokoyaku personality. Audience members are not there to wonder how glamorous her life is. Anticipating fans carry the mystique right through her embrace and veiled kiss.

In the big “kiss” scenes – and there are many hinted if not realized in each program — you never see lips touching. The usually shorter musumeyaku is facing upstage while her amour cradles her in a fond embrace, often with the “man’s” hands cupped around their mouths to hide the lips. At the moment where one projects that the actors’ lips are making contact, the otokoyaku’s signature stage dristi (Sanskrit for gaze) is beamed down upon the audience. Audience members – young and old, married or single – report strong desires to being with men who were more like the women portraying men on the Takarazuka stage.

Robertson also discusses the use of kata (stereotypical theatrical forms) in Takarazuka, but, according to Leonie Rae Stickland[v], “Takarasiennes need to resort to kata for producing gendered performance, not only because they need to use readily-identifiable gender markers to signal to the audience which gender they are portraying, but also because their scant worldly experience means they must learn gender portrayal in an ‘artificial’ manner. Although Takarasiennes are all exposed to varying degrees of socialization as girls during their childhood and early adolescence, their lack of life experience in the adult world means that they are almost as ill-prepared to play a stereotypical woman on the Takarazuka stage as to play a man.” It is up to the otokoyaku to help “his” partner learn how to behave like a woman.

Dramatic affectations for otokoyaku may include gender-specific Japanese words, such as “boku” rather than “watashi” for ‘I,’ as well as gestures that are typical of men of Japan as well as the West: tugging on the shirt cuffs, adjusting a necktie, walking with both hands in hip pockets, walking with a broader stride.

I noticed that make-up for both “men” and “women” performers are the same – heavy mascara and eyeliner, bright red lips and blushed cheeks. The boots worn by the otokoyaku in the Chinese historical drama I saw in the first act of my performance were more the type women would wear, certainly not imperial soldiers.

It’s curious too, that in Kabuki, a prized keepsake from a famous onnagata would be a piece of white silk that had been used as a blotter of the role’s kumadori, the complex make-up stylized for each role. If this were to be done by a Takarazienne otokoyaku, how deep into the multiple layers of disguise would it reveal?

Yamanashi observes, “The fans of Takarazuka and Kabuki similarly enjoy the stylized stagecraft, find joy in reading the visual and verbal codes, and more importantly, offer their attentive love that is more maternal rather than homo/hetero sexual.”

Just Everyday Hometown Girls

Dream Girls, an exceptional BBC documentary film created in 1993 about the Takarazuka world by Kim Longinotto and Jane Williams, gets up close and personal with the administrators and creative team of the Revue and its school, as well as providing candid interviews with trembling fans, and Takarasiennes and their families.

In one scene, the father of a just-retired Takarasienne stated the family’s sizeable financial investment in their daughter’s stage career had been achieved. She has left the Revue for the purposes of finding a husband. When asked why being an otokoyaku made her “ready” for the next chapter in her life, she said that because she had learned how to put on a man’s jackets she was better able to know how to help her future husband on with his as he left the house en route to work in the morning.

What these films and books also document is the profound fanbase of women that constitutes the primary market for everything from tickets themselves to objects of all sorts emblazoned with stars’ names, likenesses and even of their own designs: from bookmarks and handkerchiefs to T-shirts and other apparel and gift items. Tins of cookies and candies, calendars and magazines, as well as collectible photos, stoke and sustain a seemingly starving, loyal market.

The online Takarazuka fan club world is huge and includes non-Japanese as well. An Internet search precipitated an extensive website of Kimberly and David Ramsay, two adult Americans who collect Takarazuka ephemera that informs their love of engaging in “cos play” (costume play)[vi], Their online galleries include several pages on Takarazuka facial hair, programs, and other licensed materials, and even a connection to the web site of an “androgynous”-looking biological male entertainer.

The Takarazuka Revue is pooh-poohed by many in Japan as something only gaggles of giggling school girls and their arranged-marriage matron moms would go gaga for a fantasy fix. This would be like saying that American Hugh Hefner’s Playboy magazine is all about cute bunnies, and its value ends at the staples in the centerfold.

In closing, I was going to say that Kobayashi’s dream is a golden carrot dangled safely in front of his market to come and get it. Then I caught my Freudian slip and said, “Oh, no. You mean golden dildo.” But, on second thought, no, I don’t.

Notes:

[i]Acocella, Joan, “The Girls Next Door: Life in the Centerfold” (The New Yorker, March 20, 2006)

[ii] Scholar Makiko Yamanashi notes, most of them are originals, some inspired and less straightforward adaptations. Many are from European inspirations for Takarazuka still values its relation to France in particular. Austria is also much referred. There have been more European musical importations from early years such as Carmen, Rosen Chevalier, Elisabeth and Earnest in Love. West Side Story is usually presented as one act without the show (as Uestosaido Monogatari in 1968,1969 and renamed in original English, as West Side Story, in 1998,1999.

[iii] Yamanashi, who has been studying the commercial enterprises of Takarazuka, among other aspects, a plethora of licensed jisha (company’s proprietary brands) are heavily cross-promoted with a variety of other signature products (e.g. Shiseido cosmetics) and available in boutiques and souvenir malls that surround the two Takarazuka Theatres and throughout Japan, by mail order and now the Internet. Ms. Yamanashi has kindly shared a number of her articles with me via Internet, including “Image Branding of the Dream Factory” and “The Interactive mechanisms of the dream sellers and the dream buyers”. “Hankyu is not simply a profit-motivated industry but more importantly a culturally driven one. … The Takarazuka girls are thereby performing as the company’s face towards consumers.” Other types of products include cakes and other confections, as well as the basic necessities of matron life, such as handbags, umbrellas, sweaters, scarves, hankies, and much more.

[iv] Robertson, Jennifer, Takarazuka: Sexual Politics and Popular culture in Modern Japan (Berkeley, University of California, 1998)

[v] Stickland, Leonie Rae, Gender Gymnastics: Performers, Fans and Gender Issues in the Takarazuka Review of Contemporary Japan, Ph.D. thesis, Murdoch University, 2004

[vi] http://www.thejasper.com/trevue.html

————

Lauren W. Deutsch, director of Pacific Rim Arts, is a contributing editor of Kyoto Journal. This piece was adapted from Kyoto Journal and reposted with the author’s permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Lauren W. Deutsch.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.