The curator’s role in the performing arts area seems to be, for many—including the curators themselves—inaccurate. Regardless of the multiplication of festivals and shows, the word “curatorship” remains controversial and under construction. According to the word’s etymology, “curate” means “to look after.” The word is widely used in the visual arts. For the professor and art reviewer Roberto Teixeira Coelho (2012), it originally designated the process of organizing and assembling a public exhibition for a group of works made by an artist or by a group of artists.

Currently, for Coelho, there is a slight change in the curator’s role, which happened from the moment it was granted to him. It is the job of determining an inspiring theme for an exhibition and selecting artists and works according to his choice. We can add to this that, today, regardless of the area, it also involves establishing a relationship among works and showing this relationship to the audience.

The word “curatorship” began to be used in performing arts in Brazil after the expansion of festivals and shows, which appeared, sporadically, at the end of the 1950s, and during the military dictatorship (1965–1985), as a form of resistance against the regime. The trend was possible to discern at the Festival Internacional de Londrina (Filo) and the Festival Internacional de Teatro de São José do Rio Preto.

FIT 2016 – Festival Internacional de Teatro de São José do Rio Preto Photo https://www.facebook.com/festivalriopreto

There were other initiatives after the 1990s, thanks to the creation of mechanisms that boosted cultural production, such as the Rouanet Law, in addition to already existing local regulations and institutions supporting theatre.

A festival curator (also called an artistic director) does not act in isolation: he lets himself into a system of relations and power, inside a historical, social, political, cultural and economic context. We have to take into consideration, therefore, the characteristics and particularities of each event to comprehend the curator’s choices. The territory also needs to be reflected, from the physical space (urban or rural) to the social and cultural interactions of the communities that live there or visit it. A festival eventually boosts the economy of the city which hosts it, so the place and the context where it happens determine the development and the potentiality of the event.

Ownership of a festival can be public, promoted for the most part by city halls allied with private sponsors; or private, relying not on a public budget but on sponsors. In both cases, the sponsors mostly use public mechanisms of cultural incentive, like the Rouanet Law, to finance the festival. In Brazil, Petrobras, whose main shareholder is the federal government, began to sponsor festivals in a more effective way in 2004.

With regard to organization—conceiving, planning and hosting a festival—there is a demand for work in teams, bringing together people from different educational backgrounds and of different experiences. And, of course, the budget is defining.

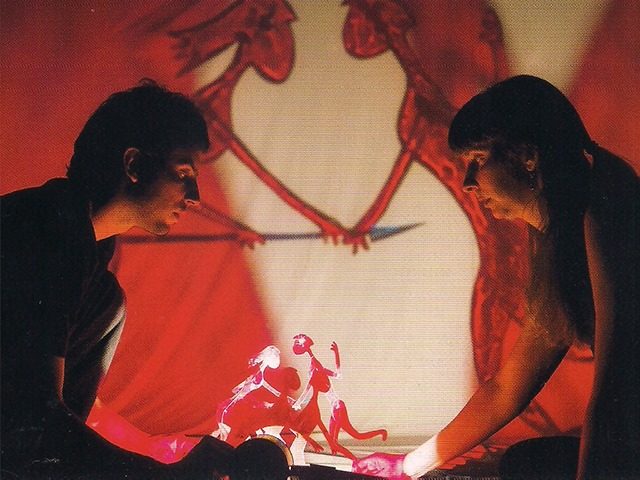

Comissura, da Cia Patrícia Pardo Teatro. FIT 2016 – Festival Internacional de Teatro de São José do Rio Preto. Photo credit https://www.facebook.com/pg/festivalriopreto

The management and the artistic models

Besides that, there is what the curator has, or should have: his focus—the festival artistic project, which includes the curatorial line of the show, ranging from the concept of what will be adopted to the choice of works, groups, and directors. The formative activities for artists and the community, in general, are also part of it. It is through an artistic project that the audience will be able to see performances that are usually not available on a regular agenda. Some curatorial projects include performances’ co-production, instigating local creation and production.

According to the director of the doctoral program of culture management and patrimony at Barcelona University, Lluís Bonet (2011), a festival is basically structured according to two models: management and artistic. The first combines strategies from financing, marketing, organizational culture and human resources to control costs and budgets, audience formation, and the capacity to set partnerships, inserting all of that in collaboration chains and managing reputation and symbolic patrimony. The person responsible for the management model is called the general-director or general coordinator of the festival; the nomenclature in this field is still under construction.

The artistic model, on the other hand, involves the curatorial proposal that originates in the festival schedule. Bonet (2011) says that the degree of independence to make decisions is relative. Many decisions result from the articulation between subjective choices and other influence agents who can exert pressure, such as the festival’s own organization and sponsors, media, and others.

The impact of the artistic project as a management model at the festival, and vice versa, depends on a good balance in the type of artistic director. In his typology, Bonet (2011) calls “pure” the curator who does not have a bond with the festival; this way he is hired only for the curatorship.

Curatorship profiles

Luciano Alabarse, curator of Porto Alegre em Cena.

Luciano Alabarse, curator of Porto Alegre em Cena.

We can find in Brazil several curatorship profiles. There are festivals where the general coordinator is also the curator. This is the case with Porto Alegre Em Cena: Luciano Alabarse underwrite the national and international curatorship in a unique task; only the local cast is selected by a curatorial council. At certain festivals, the general coordinator divides the duties with another curator or with a council. At Filo, for example, the general coordination is picked by Luiz Bertipaglia, who also shares the curatorship with Paulo Braz.

According to the other model, the general director, and the curator have different roles: each one takes a job. This is the case with the Mostra Internacional de Teatro de São Paulo (MITsp): Guilherme Marques is in charge of the general direction, and Antônio Araújo of the artistic direction. Both, however, are the creators of the event.

Finally, we have the case where the curatorial council is hired specifically for this job. At the 2016 Festival de Teatro de Curitiba, Leandro Knopfholz is hired for only the general direction; the curatorship was under the responsibility of the actor and director Guilherme Weber and the director Marcio Abreu. They substituted the producer and cultural manager Celso Curi, the journalist and manager Lucia Camargo, and the reviewer and researcher Tânia Brandão, a trio who for years would prepare the program. In the visual arts curatorship, we will find, as a rule, this last type.

When the curator is in charge of the artistic model only, the curatorial axis of the festival tends to be clearer and to have more specific duties. On the other hand, when the curatorship and the coordination is assigned to a single person, the festival tends to be personalistic. According to the journalist, reviewer, and curator Kil Abreu, it is good when the curator is responsible for the artistic model only: “The tasks are divided and, from the point of view of the artistic thought, the curator is more protected from possible production problems, which are hard to outline” (quoted in Rolim).

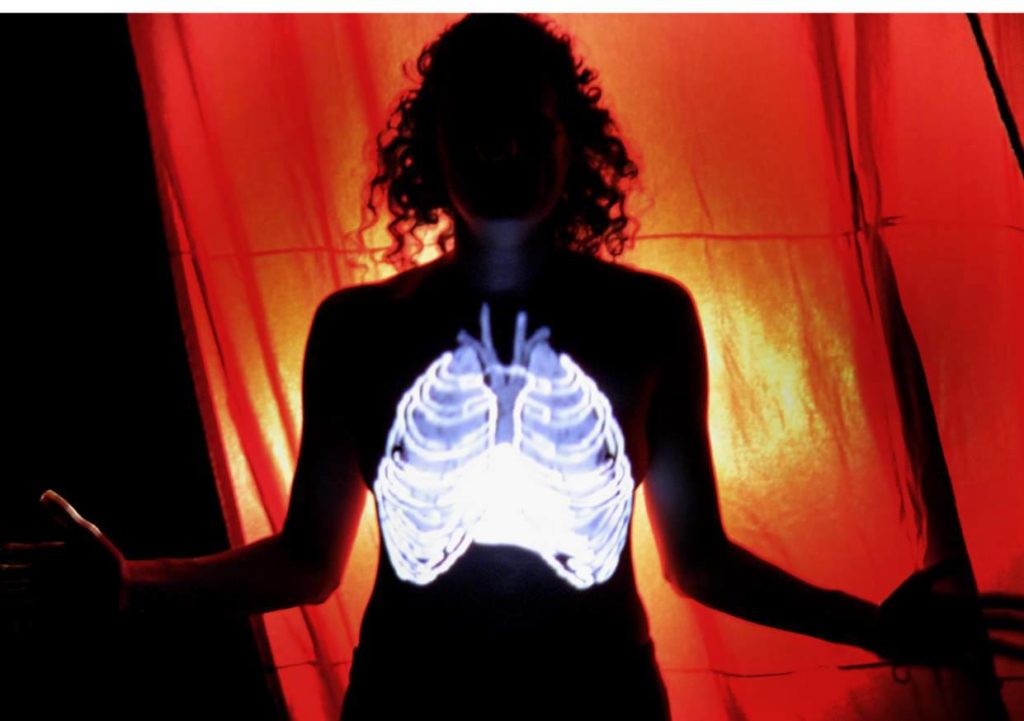

Cabeça Oca, Cia. Tangaladá – Itapira/SP. FIT 2016 – Festival Internacional de Teatro de São José do Rio Preto. Photo credit Lik Galaverna

Selective process and curatorial thought

Added to this is the selective process. We have, as a general rule in Brazil, two such processes: one gives total autonomy to the curator (without previous subscriptions to the performances) and the other pre-determinates, somehow, the universe of the curator’s choices (with subscriptions and guests).

There is also the discussion around the formation and journey followed by this professional: must the curator equate to a cultural manager? Which would be the ideal formation and the journey followed by a curator? Usually, curators of performing arts festivals are artists, journalists, or reviewers. From the analysis of these elements, it is possible to better comprehend where the choices go through in a complex and dynamic system such as the performing arts.

Currently, there are several thoughts hovering over the shows. For the director and curator Marcelo Bones (2015), there is a kind of crisis at festivals. An important issue is the lack of conceptual clarity of many events. “The festivals, today, cannot satisfy with just a collection of good performances.”

Antônio Araújo, artistic director of MITsp and director of Teatro da Vertigem

Antônio Araújo, artistic director of MITsp and director of Teatro da Vertigem.

As an example of this “concept”—or, as we can call it, this better-known “curatorial thought”—we mentioned the festival that, from my point of view, is best able to draw this idea: MITsp, whose artistic model is signed by Araújo, the director of Teatro da Vertigem.

He uses his idea of the “vibratory core” (in which there is more than one theme but they share a common dialogue) to offer the spectator a speech that relates the productions, explicit even in the text of the edition’s catalogue. It is clear that, besides the fact that Araújo focuses on the artistic model and that the show does not open for performance subscriptions, another reason why he can realize his aim is that he works with a reduced number of works in the program: approximately ten per edition. This constraint facilitates connections and allows the audience to watch most of the performances. But would this be the ideal model for the Brazilian context?

Given the differences in festivals, in terms of territories where they happen and the development of curatorial thought, we can say that there are also good festivals without a curatorial eye. The tendency that is being drawn, however, is to adopt a model closer to this one; in other words, to start building shows from a concept rather than based on a large number of productions.

*This article was written in the context of the Crítica Militante project, an initiative of the Teatrojornal—Leituras de Cena website, contemplated in the public notice “ProAC—Publicação de Conteúdo Cultural,” which belongs to the State Secretary of São Paulo.

The text was originally published in Portuguese on the Teatrojornal website on October 10, 2016. Reposted with permission. Translaed by Daniele Avila Small

References

Bones, Marcelo. “A MITsp e um pensamento sobre festivais de teatro. Observatório dos Festivais.” March 15, 2015. Available at: <http://www.festivais.org.br/#!O-Observat%C3%B3rio-acompanhou-a-MITsp-e-lan%C3%A7a-reflex%C3%B5es-sobre-os-formatos-e-curadorias-de-festivais/c3v9/55060c8e0cf2031a763d8e9a>.

Bonet, Lluís. “Tipologías y modelos de gestión de festivales.” In La gestión de festivales escénicos: conceptos, miradas y debates, edited by Lluís Bonet and H. Schargorodsky (pp. 41–87). Barcelona: Gescènic, 2011.

Coelho, Roberto Teixeira. Dicionário crítico de política cultural: cultura e imaginário. São Paulo: Iluminuras, 2012.

Rolim, Michele Bicca. Pensamento curatorial em Artes Cênicas: interação entre o modelo artístico e o modelo de gestão em mostras e festivais brasileiros. Dissertation (Master’s in Performing Arts), Programa De Pós-Graduação em Artes Cênicas, Instituto de Artes, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2015.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Michele Rolim.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.