The Melbourne Theatre Company’s (MTC) production of David Williamson’s 2013 play Rupert has finally made it to Sydney, via Melbourne and Washington, in late 2014.

Along the way, the MTC has acquired the services of American actor and Oscar and Emmy nominee James Cromwell to play the aging Murdoch. By the time Rupert was staged in Sydney (where it continues until December 20) the script had been updated to cover the latest developments in the UK phone-hacking prosecutions. Such are the demands on theatre that engages with contemporary lives and events.

Rupert is at the Theatre Royal, located only a short distance from News Corp Australia’s headquarters and also from the site of an infamous 1960 Murdoch Crew v Packer Posse fist fight over a printing press. The play roams across a Murdoch universe that expands from sleepy Adelaide to embrace London, New York, and Shanghai.

With its hyperactive ensemble cast (including well-known local actors Jane Turner and Danielle Cormack) and frantic pacing, director Lee Lewis has simulated the whirl of Murdoch’s big life. As Cromwell’s Murdoch sardonically observes the derring-do of his younger self (played by Guy Edmonds), the action unfolds in a frenetic mix of farce and cabaret.

When the MTC commissioned David Williamson to write an unspecified “big canvas” play, the UK’s Leveson Inquiry into the role of the press and the police had already become an unlikely television hit. Audiences were rapt in the nightly courtroom-style drama of tabloid horrors, thespian barristers, and squirming witnesses.

Author Kristin Williamson and playwright David Williamson in 2010. AAP Image/Tracey Nearmy

Williamson saw his chance and took on what he calls in his play the “Apex Predator” of media and politics.

There is some irony in this choice given that, despite the divergence in their politics and life histories, Williamson and Murdoch have something in common.

Australia’s most commercially successful playwright is generally regarded by Australian theatre critics as a populist peddler of middle-brow, middle-class witticisms. Its most prominent media mogul, not dissimilarly, is widely viewed by media critics and academics as achieving commercial success by pandering to the lower expectations of audiences – and then lowering them further.

Certainly, the recent review of Rupert in the Sydney Morning Herald was predictably cool. The director was praised for staving off a “theatricalized Wikipedia entry”.

There had been a minor censorship row during the play’s Melbourne run after a review in the Murdoch tabloid Herald Sun was reportedly “spiked.” Rupert did, however, receive quite favorable critical commentary in its broadsheet stablemate, The Australian.

So, as long-time academic Murdoch media watchers and researchers, what did we make of Williamson’s venture into Murdochland, and its combination of reportage, critique, and theatrical invention?

The first difficulty with theatrically doing justice to Murdoch is the sheer length and complexity of his career. He has effectively been the head of his company since late 1953, and has been involved in hundreds of deals and countless controversies.

It is inevitable, then, that any dramatic treatment must simplify and omit various aspects, (such as Australia’s own Independent Inquiry into the Media and Media Regulation), while selecting what is judged to be the most important and revealing.

We feel that Williamson has addressed this problem well, with key aspects accurately recorded while also maintaining momentum and interest.

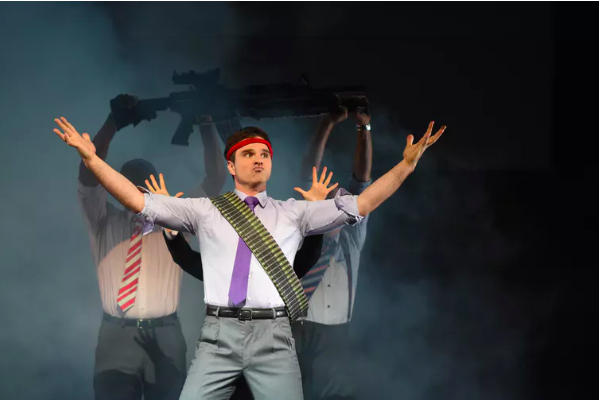

Guy Edmonds as a young Rupert Murdoch. AAP Image/Dean Lewins

Many of the pivotal developments in Murdoch’s career are treated deftly and entertainingly: his early expansion in newspapers, tabloid tastes, relationships with politicians such as Gough Whitlam, Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, and Tony Blair, movement into American TV and films, investment in satellite (especially in Britain and Asia), launching of Fox News, and his long but unrequited infatuation with China.

Only near the end does the playwright’s touch falter – with the complexities of the British phone-hacking scandal and Murdoch’s divorce from Wendi Deng chronologies becoming jumbled, and the catalog of events recited with little dramatic tension or interest.

The second difficulty with having Murdoch as the topic of a play is that there is almost a vacuum at its center. Murdoch has done many, many interesting things, but that doesn’t mean that he is an interesting person.

Are there any, as Sydney Morning Herald theatre critic Jason Blake demanded, hidden psychological depths to probe?

Murdoch is notable for his obsessive energy, willingness to take huge risks, capacity to build businesses from small beginnings, a keen eye for business priorities, driving of hard bargains, and for his ruthlessness in pursuing his corporate interests.

He is also notable for his disdain for what others consider to be professional standards and constraints, and willingness to use his media outlets to pursue political campaigns and personal vendettas.

His actions, career, and the controversies that he has provoked are full of interest, but does that make the person behind them interesting? Murdoch’s public career has given few hints of emotional complexity or of deep personal insights.

There have been few clues to him having any lasting regrets, agonizing over difficult moral choices, or wrestling with dilemmas between professional considerations and commercial advantage.

Ultimately, we are left after seeing Rupert not with an image of Murdoch as a self-conscious, Nietzschean man of action, but resembling more the relentless, goal-oriented cyborg of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Terminator.

As dramatist David Williamson found, like many media academics before him, for all the well-justified fascination with Citizen Murdoch’s impact on the world, regarding the protagonist himself there is disturbingly less than meets the eye.

This post originally appeared on The Conversation on December 15, 2014, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by David Rowe and Rodney Tiffen.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.