As the year draws to an end, Vikram Phukan lists 14 of his favorite performances from the stage.

It isn’t the easiest of tasks sorting the grain from the chaff when it comes to live theatre, one of the most ephemeral of art forms. When a performance is done, it is gone forever. Yet, in the collective memories of those who have witnessed it, it lives on long after the arc lights have dimmed. Lists are often purely subjective, but the actors featured in this one do give us a sense of the good work being done by many in a creative sphere beset with so many challenges.

Abhay Mahajan, Khwaab Sa

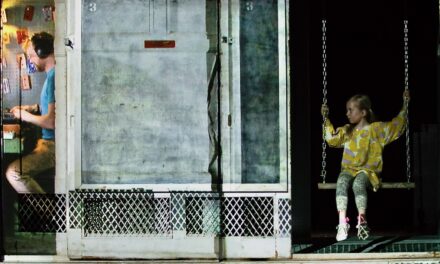

Theatre performers Abhay Mahajan (left) with Vipin Heero in Khwaab

Atul Kumar’s Khwaab Sa, devised from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, features Mahajan as one of a ribald crew of folk performers given to “Hindi gibberish.” His Bajarbattu, a stand-in for Nick Bottom, doesn’t waste time grappling with an alien tongue or the makeshift universe of “the play within the play.” Instead, he flies with each moment to deliver a revelatory performance that is both deliriously camp and intricately nuanced. It’s laced with a sliver of self-deprecation that spectacularly brings home the fool’s paradise he inhabits. Even a donkey’s head cannot detract from his undeniable flair.

Ammanur Rajaneesh Chakyar, Kailasodharanam

In an abridged excerpt from a koodiyattam performance that usually spans six evenings, Chakyar’s earth-shattering (quite literally) intensity as Ravana as he attempts to dislodge Mount Kailasa from the path of his chariot, almost in real time, is a sight to behold. The rigors of his craft are amply visible, but beyond what has been handed down centuries lies in the interpretative artistry of a contemporary performer, whose body, voice and countenance have been martialled into a spirited embodiment of living history.

Anand Grover, Landscape as Evidence: Artist as Witness

In Zuleikha Chaudhuri’s tribunal presentation, the celebrated lawyer and champion of progressives, Anand Grover plays himself in full court regalia. As he opposes a motion that seeks to propose artists as valid witnesses for litigation on environmental issues, Grover chips in a seemingly extempore turn, with all the smooth-talking persuasiveness that are inviolably a part of real-world advocacy. It is a performance that belies his so-called “non-actor” credential while providing a mirror into a legal system which is as much about showboating as it is about conviction.

Anurupa Roy, The Mahabharata

Theatre performer Anurupa Roy in The Mahabharata

In an ambitious work that she has herself helmed, Roy is intriguing to watch on stage, as she flits in and out of loaded personas. As a masked sutradhar, she gently veers an age-old text into the realm of topical politics. As the handler of the life-size Draupadi puppet, she is never the neutral puppeteer, and creates powerful and even unnerving moments. Likewise, her able handling of Gandhari’s mourning translates a golden mask and a stretch of fabric into an abject metaphor of despair and futility.

Bhavna Pani, Mother Courage And Her Children

QTP’s production of Bertolt Brecht’s masterwork is not short on bluster and invective, but it is the diligent Pani’s non-speaking part as Kamrin, Mother Courage’s mute daughter, that provides the play its flickering moral soul. Silently observing the mechanics of war-time dealings, or slinking away into the shadows, or industriously manning her mother’s cart of wares, Kamrin is a child-like uncorrupted presence, even if she chillingly bears on her person the brutalizing effects of war. Pani gives Kamrin the depth and strength that entirely justifies her eventual martyrdom.

Dheer Hira, Adrak

Theatre performer Dheer Hira in Adrak

In Adrak, directed by Niketan Sharma and Trinetra Tiwari, Hira’s character, Nischay, is forever mired in muddles—unequal relationships, oppressive work situations and the ilk. Yet his emotional vulnerability comes equipped with a self-sufficiency of its own, thanks to Hira’s bravura turn. The actor breathes life into these contradictions, offsetting the self-defeatism usually marked out for such journeymen in life with a striking survivalist streak. In the process, he creates a grappling presence with a breathtaking interiority.

Dinyar Contractor, Laughter in the House—2

Standing out in a cast of formidable stage veterans in Sam Kerawalla’s Parsi revue, Contractor inhabits the persona of a habitual complainer with a feigned cantankerousness, which never belies his essential humanism. He nimbly shuffles in and out of the show in a wheelchair as if it were a magic carpet. During one such interlude, Contractor provides the evening its pièce de résistance—a wonderfully rambling rigmarole that is full of the kind of pithy, observational humor that the septuagenarian still has a perfect hold on.

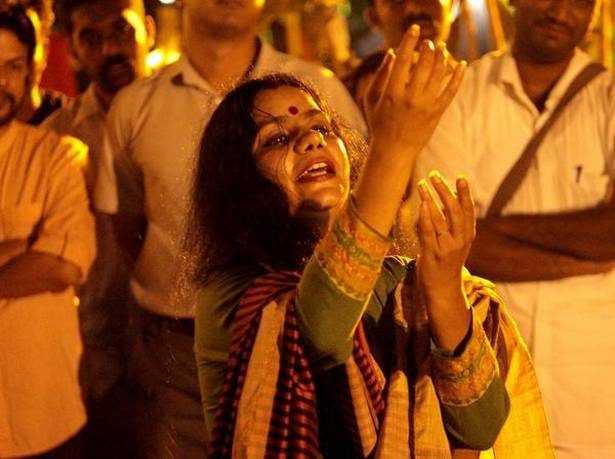

Ipshita Chakraborty Singh, Muktidham

In the thankless part of an upper-caste concubine in Muktidham, Chakraborty Singh channelises Lady Macbeth’s blood-lust and manoeuvres, as she tries to secure a future entwined with the fortunes of a prospective successor to a religious figurehead. Her Ahilya is passionate and rational, but acutely aware of her only notionally privileged status as a woman in a patriarchal set-up that is also inherently casteist. Chakraborty Singh’s complex portrayal allows Ahilya to wallow in guilt and complicity certainly but also lets her incandescent individualism shine.

Jagjeet Sandhu, Dark Borders

Theatre performers Jagjeet Sandhu with Navjot Randhawa in Dark Borders

As part of a spirited ensemble in Neelam Mansingh Chowdhry’s Dark Borders, Sandhu shows a tremendous versatility of range, either as the young boy who delivers his mother’s child on a busy street, or a man sympathetic to a prostitute’s plight. However, what is remarkable about his turn is the subversion of masculinity he ultimately achieves even in the garb of uncharitable men, conditioned to be brutes, but always open to the vulnerabilities that Sandhu wears on his sleeve with a passionate resolve.

Jaimini Pathak, Words Have Been Uttered

In Sunil Shanbag’s dramatization of staged writings around the idea of dissent, an excerpt from G.P. Deshpande’s 1974 classic Uddhwasta Dharamsala features Pathak (in one of his many parts) as the leftist professor, Vishwanath Kulkarni, summoned before a hastily convened college tribunal on account of his political affiliations. Pathak’s composure and sure-footed negotiation of this ordeal is pitch-perfect, almost like a slice of resistance served up with an icy demeanor that is both stirring and diverting.

Mikie Tanaka, This Will Only Take Several Minutes

An Indo-Japanese collaboration, This Will Only Take Several Minutes features a cross-cultural ensemble. Tanaka’s heartbreaking optimism, despite hurtling down the rabbit hole of societal dysfunction, shines like a beacon of hope. She populates a comic (yet moving) track all of her own, plodding across the city to a military rhythm in search of oddities like the “legendary salad.” As she yearns for closure in these little expeditions, there is a bitter-sweetness to her gently fierce turn and a naiveté that is remarkably comforting.

Savita Rani, RIP (Restlessness in Pieces)

Theatre performer Savita Rani in RIP

As a woman seeking to disentangle herself from the tethers of societal oppression with her instinctive solo performance, RIP, Rani’s spiel is much more than a victim’s lament. She peppers home truths about feminine repression with a disarming brand of interactive humour that is full of both self-deprecation and knowing observation. Her use of English is refreshingly unregimented, and her strong stage presence marks her out as a woman of the world, whose body is the primary evidence of the all the ordeals she has survived.

Srishti Shrivastava, Shikhandi—The Story of the In-Betweens

The feminist quotient in Faezeh Jalali’s Shikhandi is considerably buoyed up by Shrivastava’s elemental presence. Her Amba highlights her talent as a burgeoning comic tragedienne. As Draupadi, she is fiery and tempestuous, and a perfect foil (even protector) to her gawky brother Shikhandi. As the latter’s wife, she is hilariously unapologetic about her insatiable libido. In a play that stands on unsteady ground when it comes to its queer politics, Shrivastava’s “liberated woman” holds up her end of the bargain with an Amazonian panache.

Vishal Sarvaiya, Say, What?

Theatre performer Vishal Sarvaiya in Say What

In her contemporary dance piece, Say, What?, Avantika Bahl effects an unusual intersection with Sarvaiya, a performer who cannot hear her speak but can absorb the outstretched energies on offer like a sponge. A veritable force of nature, Sarvaiya’s guilelessness and warmth allows us a compelling entry point into the invisible world of the deaf, even as his physical performance, skilled yet refreshingly unstudied, challenges our notions of language and communication. He provides a revealing counterpoint, both opposite and apposite, to Bahl’s probing presence.

This article was originally published in The Hindu on December 22, 2017, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vikram Phukan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.