The 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death in 2016 provided ample room for celebrations and commiserations on Shakespeare in South Africa. The quirky title of the article stems from a 2016 student theatre festival at the University of Kwa-Zulu-Natal (South Africa) with the same name. The festival was followed by a colloquium on Shakespeare and decolonization. Decolonization has become a hot topic and the subject of vehement debate in South Africa over the past couple of years. South Africa’s university spaces are hotbeds of debate, dialogue, and dissension around the topic.

In South Africa, universities operate against the historical backdrop of universities being in Africa but not being African by definition (Ndlovu-Gatsheni 2013: 50). The extensive use of the works of the Western canon and the acceptance of the epistemological basis they are premised on (literary or otherwise) in South African academia has brought into sharp focus the tension between context and modes of knowledge production that Ndlovu-Gatsheni points out. The Apartheid regime has been abolished for more than two decades, but the residue of its injustice remains and impacts on all spheres of life. This is evidenced not only in the continued economic disparities and lack of access to resources (as epitomised by movements such as #OutsourcingMustFall and #FeesMustFall) but also in perpetuating the visibility and voice of what is perceived as physical or symbolic markers of that regime. For example, university curricula, visual symbols and language that is deemed part of that regime – the focus of movements such as #RhodesMustFall, #AfrikaansMustFall and the burning of perceived colonial works of art (Coetzee and Cassim, 2017). Students critiqued the control of power, knowledge, and subjectivity that constitute a mode of epistemological colonization that is perpetuated post-Apartheid. The ‘#MustFall’ movements point to what Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2013:46) terms an “epistemic rupture” that places academia (as a microcosm of the country) in a mode of interregnum – where a hitherto dominant epistemic order becomes exhausted and the way towards a new order starts to surface.

Shakespeare, as a central marker of the Western canon, has become a target of the decolonial turn. Calls to remove Shakespeare from school and university curricula surfaced strongly in 2017 and stimulated vehement and continued debate. Shakespeare was, and is, a widely prescribed author in educational institutions in South Africa (and on the continent of Africa); his works have often been critiqued as reflecting colonial mindsets but have also been invoked as sites of/for resistance. The critique, amongst others, is due to his perceived uninterrogated representation of codes of mastery in terms of race and gender, and his ideological weight as an icon and symbol of cultural domination. In response, a number of scholars proposed alternative readings of Shakespeare in stressing the political dimensions, social processes and material conditions in some of his work that resonate with themes of social justice and with postcolonial and post-liberation contexts. In a 2017 review of Matthew Hahn’s play, The Robben Island Shakespeare for a special edition of the journal Shakespeare in Southern Africa on decolonizing Shakespeare, I stated that:

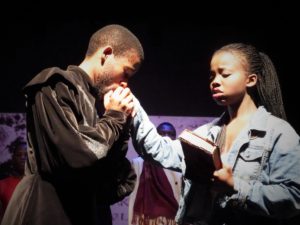

Lady Macbeth, Yolisa Mkhize in The Past is Prologue. Photo: Donna Steel

The contested position of Shakespeare in South Africa foregrounds an ambiguous synthesis of memory, ideology, coercion, and power… Amongst the multiple translations, adaptations and transpositions of Shakespearean texts in South Africa and indeed the continent, questions about the extent to which a canonical text can be divorced from its ideological anchors, be divested of authority and transcend a dominant representational or interpretive center, remain.

These are some of the issues that South African universities grapple with in their engagements with Shakespeare. In 2016, when events across the globe marked the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, South African universities followed suit. Many drama/theatre departments presented theatre works that engaged to some extent with Shakespeare and the decolonizing impulse. For example, the #ShakespeareMustFall? theatre festival with participating organizations including amongst others the University of Kwa-Zulu-Natal (henceforth UKZN), Durban University of Technology, and the Durban campus of ADFA: the South African School of Motion Picture Medium and Live Performance; The University of Pretoria’s (henceforth UP) three-tier experiment with Shakespeare and decolonization; and the Tshwane University of Technology’s Mosiuoa (Hamlet). These productions contemplated what it means to decolonize Shakespeare. For some universities, student protests in the #Must Fall movements saw these celebrations spill over into 2017 due to suspension or extension of academic programs in 2016. I will engage with the UKZN and UP productions for the remainder of the article, with a central focus on UP’s production of uMabatha.

UKZN’s The Past is Prologue both celebrates Shakespeare’s works as part of a Western canon of works and problematizes the status of these works through in the post-Apartheid, postcolonial South African context. The title references The Tempest and is, as director Tamar Meskin states, “deliberately ambiguous: it offers both the potential to abandon the past in favor of the glorious future waiting ahead, but also may point to the importance of the past in shaping both the present and future.” The production overtly played with this ambiguity. The production concept mainly hinged on two questions as per Meskin’s program note:

What would happen if Shakespeare were propelled into a future, not unlike our own, possessed of nothing but his own words, and finding himself in a world where his works have been reduced to museum-like artifacts of a great tradition? What would happen if he was given the opportunity to speak to this present and in so doing shatter the glass that separates his works from his living audience?

Demonstrating her considerable skill as a director, Meskin created an imaginative theatrical collage fusing past and present. Using excerpts from selected Shakespearean works, together with original writing and adapted works, Meskin wove together a story about a time-traveling Shakespeare and created a production that engaged with a range of discourses and counter-discourses involving dominance, race, gender and language in relation to Shakespeare in/and South Africa. In literally transporting William Shakespeare to our present times, he is forced to engage with the world where his works are a relic of an ancient past; both revered and hated; used as a mechanism of Western imaginations to reinforce a standpoint of mastery and cultural supremacy. In this world, the resurrected Shakespeare is offered a platform “to speak to this present” (Programme note 2016).

Sfundo Sosibo as Shakespeare and Zibuyile Mkhize as Siri in The Past is Prologue. Photo: Donna Steel.

This central premise of the work allows the production to problematize the ownership of meanings related to Shakespeare and his works and to interrogate the relationality of the past, present, and future by “reinscribing his works with newly imagined meanings” (Programme note 2016). Meskin’s position is that “when we (re)invent, (re)inscribe, (re)write that meaning, we are, in essence, decolonizing that play for our own time and space and purpose” (Programme note 2016). The question as to who can or should forge an act of decolonization remains to be interrogated.

The University of Pretoria chose to present The Merchant and Veronica directed by Thabiso Qwabe, De-Coriolanus directed by Myer Taub, and uMabatha directed by Josias Dos Moleele. Merchant localized characters, language, and setting, as well as abstracted and physicalized the mode of performance whilst playing with gender. De-Coriolanus dealt with ideas around “expansion, loss, politics, technology, human, anticipatory consciousness…applying ideas of critical distance, action, absence into the production concept” (Program note) in deconstructing the text. The third production was a reinterpretation of Welcome Msomi’s 1970/1 play, uMabatha (Macbeth). Around the time that Msomi developed uMabatha, other such projects (in specific literary translations and adaptations) were also developing including amongst others Mdledle’s Xhosa translation, uMacbeth (1960); Raditladi’s Setswana translation, Macbeth (1967); Erlank’s Afrikaans translation, Macbeth (1965); and Stephenson’s film, Maxhosa (1975). For a comprehensive overview of the literary translations and adaptations of Shakespearean works in South African languages in this period, see A bibliography of Translations of Shakespeare’s Plays into Southern African Languages. In his foreword to the English playtext of uMabatha, Mazisi Kunene wrote that “[n]o greater tribute was ever paid to an author who lived many centuries ago than this one” (1996: sp).

Welcome Msomi’s uMabatha

uMabatha is a landmark work in thinking around Shakespeare and decolonization. uMabatha was born from the fusion of Msomi’s engagement with Shakespeare, as well as the embodied and indigenous knowledge(s) and histories that his cultural background (Zulu) offered; indeed, it became popularly known as ‘the Zulu Macbeth’. Centrally, Msomi resituated and reconstituted the geographical, topographical, contextual and temporal dimensions of Macbeth, de/re-historicized central themes in Macbeth, and merged history and fiction to create a play that resonates between the pronouncedly different cultural and historical contexts of Elizabethan England and 19th century South Africa. By asserting his African identity in and through the medium of theatre, Msomi activated the potency of his artistic voice and offered a cultural transposition of a Western canonical text that has inspired responses from artists and scholars alike. Whilst many scholars view uMabatha as constituting a mode of decolonizing Shakespeare and as an example of transculturation, uMabatha has also been the subject of heated debates that invoked Fanonian and Barthesian readings of the work, prompted reproaches of acculturation, and critiqued its representation of identity. It is specifically these tensions that make uMabatha such valuable educational resource, whether studied as a playtext or explored in performance.

Mabatha (Macbeth), Thabane Khuzwayo and Kamadonsela (Lady Macbeth), Indi Mguqulwa. Photo: Spiro Schoeman.

In his personal preface to the published playtext (1996), Msomi’s confesses that his love for Shakespeare started during his years at the St. Christopher’s High School in Swaziland. Returning to South Africa, he formed the Black Theatre Company (BTC) in 1965 in Durban. Based on the success of the plays he produced with the company, he was invited by Elizabeth Sneddon of the then Department of Speech and Drama at the University of Natal (now UKZN) to present one of his isiZulu plays at the university. The oppressive political context of the time limited spaces and opportunities for black artists, and Sneddon advised him to write a play based on a well-known epic so that a broader and international audience could follow his artistic voice.

Msomi saw parallels in the narratives of Shakespeare’s Macbeth and South Africa’s King Shaka kaSenzangakhona (Shaka Zulu) and so began the process of developing uMabatha. Reportedly, Msomi performed as Mabatha/Macbeth in a 1970 iteration of the play, directed by Pieter Scholtz (McMurtry 1999:311). As a public performance, uMabatha premiered at the Open Air Theatre at the University of Natal in 1971. In 1972, Msomi received an invitation to close the Royal Shakespeare Company’s World Theatre Season in London with his play, which broke box office records in 1973 at London’s Aldwych Theatre. uMabatha traveled the world for 9 years to critical acclaim. The play was revived in 1995 on request of Nelson Mandela.

It was during this period, whilst lecturing at the University of Zululand’s Drama department, that I had the privilege to see uMabatha at the Playhouse Theatre in Durban. Performed in isiZulu, the dynamic crystallization of performance intent, the exceptional choreography, the clear directorial vision and the determined assertion of transvaluation etched the production into my mind. Twenty-two years after I saw uMabatha, a chance to engage creatively with the play at UP arose – at a time when debates around notions of identity, indigeneity, and decolonization are at a peak.

Tshegofatso Mabele and Nelisiwe Mabena (dancers at the feast). In the background clockwise: Nadine King, Chad Jiminez, Zizi Waters, Zamah Nkonyeni and Nande Jordan. Photo: Spiro Schoeman.

The department brought together a team consisting of director Moleele; choreographer Luyanda Sidiya; set designer Karabo Legoabe; costume designer Nthabiseng Makone; and lighting designer Ole Boinamo to reinterpret Msomi’s uMabatha. The main focus of the project was to explore how a multicultural, multilingual student body would reconstitute the main drivers of identity in the play and how that would interplay with representation and meaning-making in a contemporary context. Welcome Msomi generously made the performance rights available to the department.

Drama students and members of the Usuthu community theatre groups from the townships of Atteridgeville and Mamelodi participated in this re-interpretation of the play in 2016. In the 2017 iteration of uMabatha, only drama students participated. Moleele’s chose to work with the themes of abuse and the corruptive potential of power and unchecked ambition; greed and deceit; tyranny and oppression; and fate vs. free will. Moleele used a multicultural cast, cross-race, and cross-gender casting, as well as (re)transposing the cultural context of the play. In doing so, he played within the current social and political context to explore multiple layers of signification in relation not only to Msomi’s, but also Shakespeare’s text. His directorial interpretation simultaneously referenced and shifted the cultural framework in which Msomi’s play was located (through mise-en-scène, dramatic language, the juxtaposition of tradition and contemporaneity, and a multicultural cast).

Moleele covertly extended the points of convergence that Msomi saw between Elizabethan England and 19th century South Africa, to contemporary South African leadership. His directorial treatment of the play offered ample material for discussions not only about the central themes in the play and the complexities of cultural transpositions but also more broadly around representation; articulations of difference; the intricacy and multiplicity of our identities and histories as South Africans in relation to those of others. The questions remain: where do the new meanings the reinterpretation conjured up leave Msomi’s uMabatha and where to these meaning, symbols, and images shift the initial decolonizing impulse of the work? The production continuously unfolded layer upon layer of questions and positions to create a network of unresolved dialectical tensions.

Isangoma (deviner): Zenande Picane. Photo: Spiro Schoeman.

To some extent, this was the case in both the UKZN and UP productions. Both productions further foregrounded questions around the voice of the director and possibilities for renewed cultural colonization and cultural appropriation. Considering that directors do not only ‘perform back’ to the text/texts they reference but to an entire discursive field within which the text/s initially functioned, figuring out how to decolonize a text whilst leaving enough of it to allow for a point of reference to – and point to the representation of – the specific text/s is challenging. Additionally, selecting specific Shakespearean text/s at a particular moment in time and space, at a specific historical juncture, rather than doing/writing any other play says as much about the director as it says about decolonization or Shakespeare. Should Shakespeare be decolonized? Having no standardized markers, methodologies or formulae for decolonization, the central questions of not only how to decolonize and also what to decolonize in which contexts, but also by whom remain as we look to the future.

The experiments with Shakespeare and decolonization at South African universities offer an invitation continually to engage with revisionist impulses and understandings of the entanglement of artistic products, histories, power, ideologies, and contexts that compel us to recognize possibilities for change. They challenge director and students alike to harness their South/African identities and the power of theatre to shape a ‘glocally’ relevant artistic voice. Moreover, they offer an invitation to engage actively with epistemic ruptures through artistic endeavors and vision a future of – what Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2013:51) terms – “pluriversalism.”

Sources consulted

A bibliography of Translations of Shakespeare’s Plays into Southern African Languages. [sa.]. Prepared by the reference staff of the Durban Municipal Library. http://journals.co.za/docserver/fulltext/iseasosa/2/1/63.pdf?expires=1504547774&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=C57BB4641ECAF0A454A572D0869B2057

Coetzee, M-H & Cassim, F. 2017. Educating T-shaped citizens: a theoretical proposition for the role of the arts in critical citizenship education in South Africa. Forthcoming.

Coetzee, M-H. 2017. Review: The Robben Island Shakespeare by Matthew Hahn. Shakespeare in Southern Africa. Forthcoming.

McMurtry, M. 1999. “Doing their own Thane”: the critical reception of uMabatha, Welcome Msomi’s Zulu Macbeth. Ilha do Desterro. (36): 309-334.

Msomi W. 1996. uMabatha. Hatfield: Via Afrika.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. 2013. Decolonising the University in Africa. The Thinker. Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg. (51):46-51.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Marié-Heleen Coetzee.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.