Intercultural Interlocutors: Tay Tong and Faith Tan, Part I

*This is part 1 of a 3 part article. Read part 2 here, read part 3 here.

With Singapore’s geographical location and cultural dislocation in Southeast Asia, the country has been ripe for artistic collaborations that reframe its relationship with the region. Singaporean arts managers have become intercultural interlocutors of sorts, connecting Singapore and its neighbors through the performing arts.

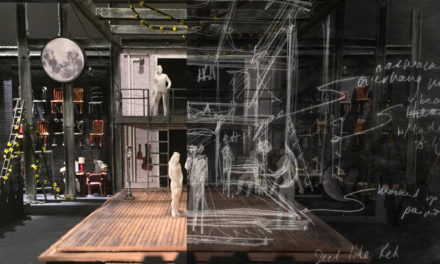

Independent performance company TheatreWorks, formed in 1985, has long been at the fore of these intercultural negotiations. Its arts space 72-13 is not only dedicated to the development of contemporary art in Singapore, but also to the evolution of a broader Asian identity, and acts both as an incubator for artistic experiments as well as a center for research and development for processes across disciplines and cultures.

Image of Faith Tan by LASALLE College of the Arts.

Image of Tay Tong by Wesley Loh.

Tay Tong, who joined the company as a producer in 1989 and eventually became its managing director, produced TheatreWorks’ Flying Circus Project, led by the company’s artistic director Ong Keng Sen since 1996. The project has acted as a catalyst for cultural exchange for artists from the region and the rest of the world, and a stepping stone for new company initiatives such as the Curators Academy (2018).

Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay is Singapore’s national performing arts center and one of the busiest arts centers in the world. It often works in close partnership with local, regional and international artists to develop artistic capabilities. It has presented more than 37,000 performances and drawn more than 26 million patrons since its opening in 2002.

Faith Tan is the center’s head of theatre and dance and has been with the institution since 2003. She steers its flagship da:ns festival, which enters its 13th edition in 2018. Esplanade has supported over 300 new works from Asian artists in the last five years and invested in a number of capability and knowledge development programmes. These include da:ns lab, an annual platform for dance practitioners to reflect on key issues surrounding their creative practice.

Tay Tong and Faith Tan discuss Singapore’s place in Southeast Asia and some of the work that has gone on behind the scenes of their projects. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Snobbery and engagement

How do you think Singapore tends to position itself in relation to the rest of the region in terms of the arts–and how do you think that relationship has evolved from the time you first started working as a producer?

Tay Tong: I’ve always felt that we can’t really talk about Singapore without looking at its position in Southeast Asia. Singapore is very much a part of Southeast Asia not just geographically, but also historically. We are so porous as an island state, so much so that our Southeast Asian neighbors are, in a sense, our hinterland for trade, for economics, for any kind of development.

Back in the 1970s and up to 1990s when we first did the Flying Circus Project, there was a sense—from my point of view—of some kind of a snobbery towards our Southeast Asian neighbors, despite the fact that we are all bound together by ASEAN. In terms of the arts, we were not looking so much towards our Southeast Asian neighbors. There was very much a positioning of Singapore in relation to Europe, to the more developed Asian countries in East Asia and in North Asia, and to North America.

I remember that in 1991-1992 when TheatreWorks wanted to do an ASEAN season–it bombed. At the time, we were so used to having a ready audience. One of the plays was Trip to the South by Tony Perez, and it was directed by Nonon Padilla – a Filipino play directed by a Filipino director working with Singaporean actors. The other work we had was by Arifin C. Noer from Indonesia, and he directed Singaporean actors like Lim Kay Siu and K Rajagopal. The third work was with Malaysia’s Five Arts Centre, which brought down a three-weekend festival comprising visual art, installation art, and performance. Then there was a Singapore Season that was largely made up of new Singaporean writing.

But the audience was not quite ready for the ASEAN season, so the only success was the Singaporean work. But that never stopped us. Culturally, Southeast Asia is so rich, and there was so much that we young Singaporean practitioners did not know about. We wanted to engage because we didn’t feel culturally adequate; we are a very young country, but their cultures go back centuries.

Long-term relationships

Faith Tan: Speaking from a position of how Esplanade relates to the region, it is important that we work closely with Southeast Asian artists and producers to stay connected to developments within the varying scenes, and respond by supporting projects that resonate within our programming or address a critical need.

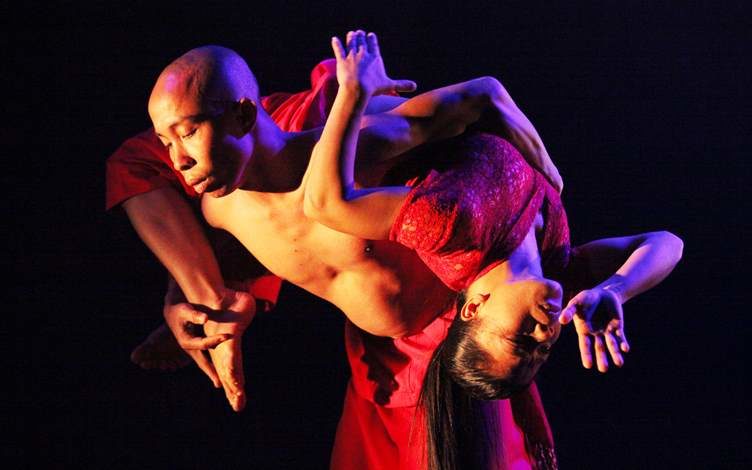

We do so through many annual festivals and platforms, where we are increasingly supporting new productions from the region. These platforms include Pesta Raya, our Malay festival of arts which explores both the traditional and contemporary face of the Nusantara (Malay Archipelago), and da:ns festival, where we have taken a leading role in commissioning and creating work with Southeast Asian contemporary dance artists because there has been a void of such regular support.

Pesta Raya: Tarian Malam by Nan Jombang Dance (2012)

The position we take is a long-term one. For example, Esplanade’s relationship with Thai dancemaker Pichet Klunchun began in 2007 with the presentation of one of his smaller productions. This marked the beginning of many years of working together, from showcasing his classical Thai Khon dances for free in our outdoor spaces to commissioning full-length productions. This continued support enabled him to form a full-time dance company, and tour productions internationally.

Being able to present his work regularly allowed us to develop audiences, and we’ve taken care to contextualize and inform audiences of not just an artist’s productions, but the context of their practice too. With Pichet’s last work at Esplanade, we created a pre-show talk by his dramaturg on the history and key points of Pichet’s career thus far, as well as an exhibition of Pichet’s drawings of dance poses that form the foundation of his dance from his classical roots.

How did the earliest intercultural projects in Southeast Asia score funding? How does one balance long-term collaborations alongside spotting and giving a platform to emerging artists?

This article originally published by Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay, Singapore on August 29, 2018, at www.esplanade.com/learn. Reproduced with permission courtesy of Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Corrie Tan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.