New concept and new management: The Wiesbaden Biennale 2016 set out to search for a European identity. A classical theater was not to be seen there.

Where does reality end and madness begin? It was not that easy to find out in the Domo de Eŭropa Historio en Ekzilo museum, located in a court building in central Wiesbaden that had been standing empty for some time. Visitors wandered around unaired rooms where the past had collected like litter. This museum looked back from a distant future on a controversial present-day project: the European Union (EU), presenting its achievements and ideals merely as the dusty exhibits of an experiment. This swan song was conceived and designed by Belgian Thomas Bellinck. While himself speaking of “constructive pessimism,” he led visitors very close to reality in presenting Europe’s demise. His fake museum also collected documents on the “Mediterranean mass grave,” where it is difficult to tell where reality metamorphoses into fiction. A sign makes reference to Budapest bombings that led to the first pan-European pogrom. A dark vision of the future, as is the Schengen place-name sign carelessly discarded in the corridor.

TEXTS AND AUTHORS

Thomas Bellinck is one of the artists of the Wiesbaden Biennale 2016 who presented works conceived for particular rooms in Wiesbaden under the city’s The Refuge of the Tired European Residency Programme. The aim of the newly-conceived Biennale was not only to open up boundaries towards other art forms, but also towards the city and its inhabitants: “We want the city to live with the artists and vice versa” said Maria Magdalena Ludewig, a theatre director, who curated the eleven-day festival in collaboration with Martin Hammer, a dramaturge. They succeeded Manfred Beilharz, who set up the theatre biennale New Plays from Europe in Bonn in 1992, which he later continued in Wiesbaden until 2014. His festival, designed in collaboration with Tankred Dorst, was based on the recommendations of many dramatists from across Europe, so-called patrons, who put forwards suggestions from their respective countries. The focus was always on texts and authors, whereby the definition of “play” gradually widened in the festival programme of recent years.

Uwe Eric Laufenberg, who succeeded Beilharz as director of the Hessisches Staatstheater Wiesbaden in the 2014/2015 season, did not want to continue his predecessor’s festival in the same form. He entrusted Ludewig and Hammer with the task of developing a new concept for it. Their Biennale too, has turned its attention to Europe, but the outlook has broadened: borders have become blurred, both between nations and between different artistic genres.

PERFORMANCE AND INSTALLATION

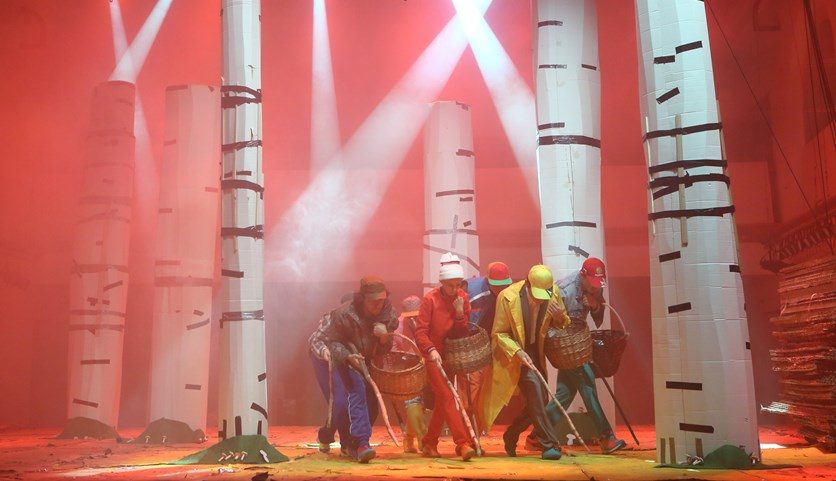

Under the title This is not Europe, which promises everything and nothing, the two curators brought the festival up to date. Their guest performance programme presented highlights, absurdities and big names. They did not stage any plays in the very traditional sense of the word. Some pieces used no language at all, while others relied on researching their subject or sought salvation in taking a performative approach. The trends of contemporary theatre were reflected more strongly in The Refuge of the Tired European, the Biennale’s second supporting pillar, in which audience participation was often requested, when indeed the audience did not become an integral part of the performance. Such participative and immersive approaches often went hand in hand with the insight that authorship nowadays is bound neither to artists themselves nor to play scripts.

A leitmotif of the festival programme was the question of European identity. In Beilharz’ time, this was a composition of many different European identities, while this time it presented itself primarily as the search for a common identity. Already at their first performance two years ago, the two curators announced that the question “How does it feel to be European” should be at the heart of their festival.

Dutch artist Dries Verhoeven took this idea further by literally carrying our values and ideas to the grave. The bells of the small Church of St. Augustine of Canterbury began to chime at 6 p.m. on ten days of the festival. On one occasion, it was time to say goodbye to the multicultural society, on another, to Mother Nature. Initiates were dressed in black, a vicar – an actor – spoke words of reflection and comfort, the sound of an organ sanctified the site, prayers were said, and the air was heavy with incense. The funerals, which followed the rites, were not only great fun, but also a serious reflection on the state of the present age. Thus, in a pleasantly unexpected way, the newly-conceived Wiesbaden Biennale picked up on the city’s Fluxus tradition that people prefer to forget. This artistic movement, with its foible for happenings of all kinds, established itself in the city in the early 1960s. “This is not Wiesbaden,” some people might have thought back then. This saying was back this year to adorn the festival office of the Wiesbaden Biennale.

Translation: Jonathan Uhlaner

This article was originally posted on Goethe.de. Reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Shirin Sojitrawalla.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.