The Curitiba Festival, which runs from March 28 through April 9, celebrates its 26th edition in 2017 and presents itself as one of the main events on the theatre calendar in Brazil. If not long ago this happened because of its impressive budget and number of offerings, today its importance refers to other factors.

Before presenting this edition, it may be relevant to return briefly to the method by which this festival was being presented two years ago, before a change that brought, among other things, new curators. In 2015, the opening night was marked by a last-minute show substitution, which brought to the stage of the grand auditorium of the Guaíra Theatre Cinderella, a classic ballet from the Guaíra Ballet Theatre. After the performance, the guests were welcomed to an enclosed square in front of the Theatre. The opening night presented the literal isolation of the square – something that, combined with the presentation of the classical ballet, seemed to establish the beginning of an elitist event, one that enclosures public spaces, creating too big of a fissure to be disregarded or ignored. On top of that, the shows of the Official Exhibition (Mostra Oficial) in that year came mainly from the Rio–São Paulo hub, and had extremely commercial and marketed features. For a festival that introduced itself as “the window to Brazilian Theatre,” it lacked a diverse event program, making it impossible even to mention an experimental theatre that could highlight contemporary discussions on the field.

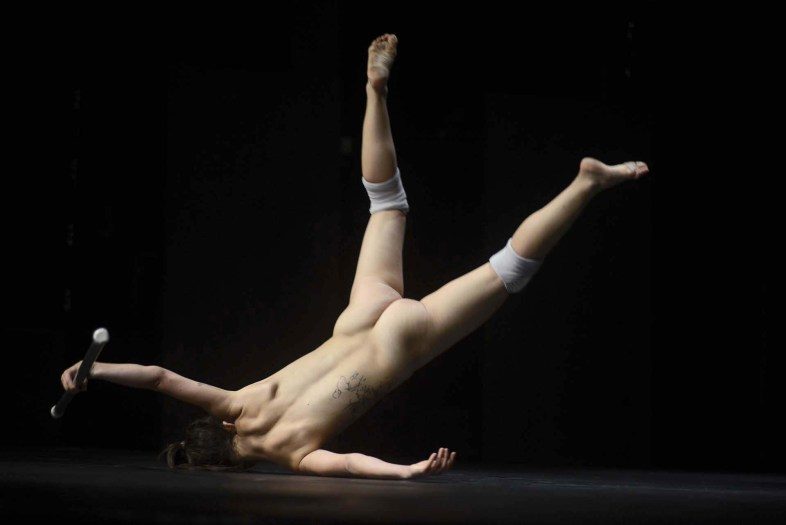

Nossa Senhora da Luz (Our Lady of Light) by the collective Toda Deseo. Photo credit: Mirela Persichini.

There has been a recurring viewpoint , especially among local artists, that demonstrates a complex and paradoxical relationship with the festival. If, on one side, the city, for a little more than ten days, relates intimately to the theatre, during the rest of the year the current feeling is of complete forgetfulness on the part of the public and the press, as if Curitiba were conditioned to consume theatre only for a big event of short duration. Another frequently discussed matter is the number of attractions that makes it impossible for one to experience the festival as a whole. It is much more about not being able to see things than the opposite. This limitation is due to two main factors. First, the large number of shows, with many attractions taking place at the same time in separate locations. Then there is also the fact that the majority of the shows of the Official Exhibition are sold at R$70,00 – which prevents people from being able to watch a considerable number of performances, what you would expect from a festival. Someone who wished to see one play a day during the 12 days of the event would spend R$840 if he or she were to pay full price – a value completely disproportionate to that of similar events, such as the MITsp in São Paulo.

The festival is divided in two big exhibitions: the Official Exhibition, which is curated, and the Fringe Exhibition, for which one merely has to sign up to participate. Of course, it is possible to follow part of the festival at no cost, since many of the shows that compose the Fringe have free admission or perform in the street. It is common to hear people say that, when introducing several possibilities, the festival doesn’t exactly turn into a diverse event, as it establishes very clear differences between audiences attending specific acts and spaces. Several of the festival locations continue to be quite restricted. Can we talk about diversity, like accessibility, when we give access to restricted venues by limited audiences? What do these distinct programs indicate? In reality, these are only some of the multiple questions that a big event as such allows us to raise, since there is no ideal format, as we know.

Curators Guilherme Weber and Marcio Abreu.

In 2016, however, a change in the festival’s curatorship was highly celebrated and publicized. Marcio Abreu and Guilherme Weber took on the curatorship of the Official Exhibition, already introducing significant shifts in the structure and methods of conceptualizing and presenting the festival. The desire to contemplate diverse demands and to make the festival’s location and thematic more political were evident. Hybrid works between dance and theatre, performance art, musical acts, and shows with themes that articulated different forms of life and understandings of the world integrated a considerably varied program.

In addition, it was very interesting to see how the festival managed to establish, for the first time, a wider program for artistic fruition. Conversations with critics and artists, parallel events, formative activities and book launches were important happenings and opportunities to think over other possible relationships between the arts and the city.

Thus, in 2017, the work carried on by curators Abreu and Weber seems to deepen and improve some matters that had already emerged in 2016. The inspiration for the curatorial choices comes from an aphorism from the Anthropophagous Manifest (Manifesto antropófago) by Brazilian modernist writer Oswald de Andrade: “I am only interested in what is not mine.” The thematic axes of this year’s festival are Women and Identities, Otherness, Collectives, Resident Artists and Coproduction, Public Space, Humor, and Social Criticism and Dialogues.

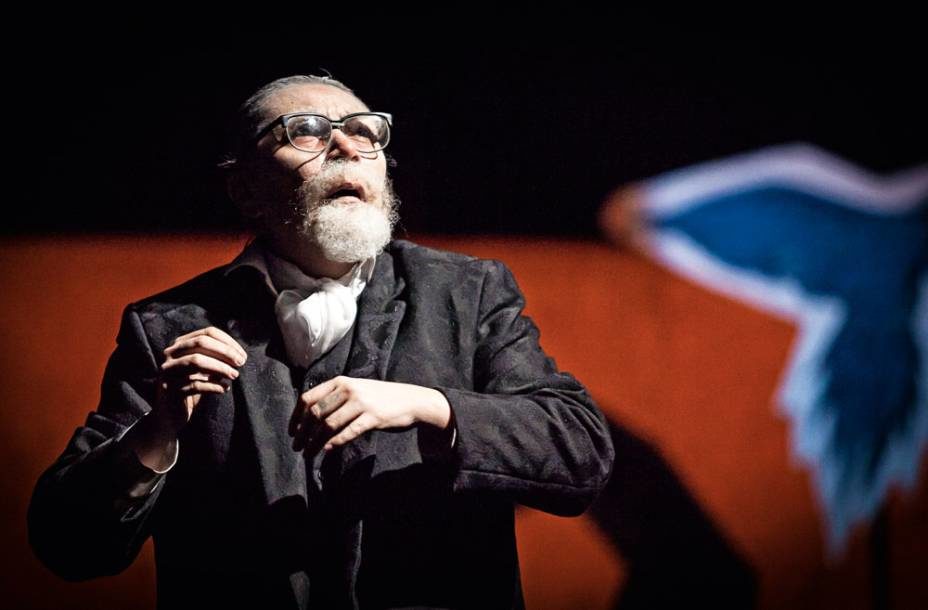

Olympia by Vera Mantero. Photo credit: Jorge Gonçalves.

Intending to show how recently the Curitiba Festival has filled in blanks that were pointed out as flaws, at the risk of sounding unfair, I would highlight the following works and actions:

– Curitiba Mostra II, idealized by Gabriel Machado and Nena Inoue, which introduces original performances created by unprecedented partnerships between artists from Curitiba.

– MOVVA, a space for dance workshops, in which artists like Lia Rodrigues and Vera Mantero will participate.

– Meetings to discuss the relationship between curatorship and criticism regarding theatre and dance, organized by Daniele Avila Small and Sonia Sobral, presenting panels with Brazilian and other Latin-American professionals.

– Debates with theatre critics convened by the DocumentaCena platform, with Ivana Moura (editor of the Satisfeita Yolanda blog from Recife), Luciana Romagnolli (editor of the website Horizonte da Cena from Belo Horizonte), Mariana Barcelos and Patrick Pessoa (both from the review Questão de Critica from Rio de Janeiro).

– The showing of the movie O rei da vela (The King of the Candle), directed by Zé Celso Martinês Correa and Nilton Nunes, with the attendance of Renato Borghi, Amir Haddad, Elcio Nogueira and the directors.

Juliana Galdino in Leite derramado (Spilt milk) Photo credit: Edson Kumasaka.

– Workshops and lectures, with artists such as Amir Haddad, Juliana Galdino and Wagner Schwartz.

– Works of women such as Fernanda Montenegro, Grace Passô, Fernanda Torres, Juliana Galdino, Andrea Beltrão, Denise Stoklos, Christiane Jatahy and others.

– Street actions such as GayMada and Nossa Senhora by the group Toda Deseo.

– Works that focus on racial discussions such as Macumba: Uma gira sobre poder (Macumba: A “gira” about power), developed by a partnership between Núcleo de Teatro de Alagoinhas and Companhia Transitória.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Francisco Mallmann.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.