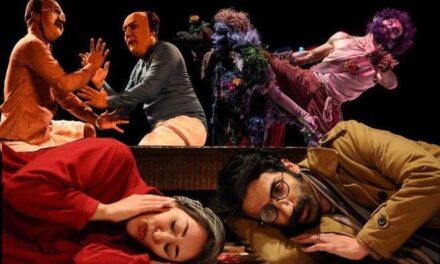

The Mafia, written and directed by Afrooz Forouzand, invites audiences to a mysteriously complicated game for an hour and twenty-five minutes. The play narrates the incidents happening to people attending a goodbye party held by Mahnaz and Ahmad on the occasion of their immigration to the United States. The seven friends who attend the party participate in Mafia,1 a game in which the majority are to guess the identity of the mafia, who constitute the minority. Suspicion, distrust, betrayal, denial, and lying are the feelings and behaviors that the players should experience during the game. Mafia gradually molds the characters and their relationships.

Gradually a mystery is shaped by a woman’s voice played from backstage. She talks about her confusion and despair, the result of some painful experience in the past. This confronts the audience with questions: Who is she? What is her relationship to the people at the party? What is her story? The woman’s mystery is intermingled with the suspenseful and uncanny Mafia game and turns the audience into a player who in turn accuses the characters suspiciously and is looking for the real mafia.

“Who is the mafia?” is the game’s principal question, which the players keep repeating. As we hear the players’ words and put together the puzzle pieces of the woman’s story, which are scattered around her and other people’s narrations, we realize that the main players are not the seven friends, but the voice of the absent woman and her husband. To put it more clearly, these two absent characters are the source of the play’s dynamism and give meaning to the rest of the characters and their actions. Little by little, it turns out that all seven friends have an irritating subconscious preoccupation, which is related to the voice of the absent woman, Monir, and her husband, Shahram. As the Mafia game develops, the mystery of Shahram and Monir is disclosed, and the story which connects these seven people to the woman’s voice is shaped.

The players, who, according to their roles in the game, incessantly accuse each other of being the mafia or deny being the mafia, begin to blame each other for the ordeal Shahram and Monir underwent, and to deny their role in it. The first turning point happens when Hedayat suddenly stands in front of his friends in the middle of the game, saying bitterly: “I’m suspicious of you all! I hate all of you! I hate myself!” This is where the game of Mafia is actualized, and suspicion, denial, and lies break through the fragile wall of fantasy and travel to the real world. Through the players’ dialogues, the audience finds out that they had lost Monir and Shahram on a trip to Istanbul they had planned two years ago. Shahram, who had been barred from foreign travel by the government due to his political activities, was arrested on the border, and left Monir to wander after him. The friends did not cancel their trip to inquire about what became of Monir and Shahram and to help them, and continued toward their planned destination. Now, after two years, each of them is struggling with the sense of guilt resulting from having betrayed their friends.

It’s as if Monir’s voice, played in different sections of the play, is the voice of their conscience, combating their monstrous sense of guilt. Meanwhile, their quarrels about the unlucky event two years earlier are interrupted by the players’ monologues, which are addressed to the audience. The characters, in turn, step away from the play and make confessions. It’s as if, unable to convince their friends, they are holding on to the audience’s judgment, hoping to attract their sympathy to reduce their sense of guilt. Among these four people, who all offer excuses for their shortcomings with regard to Shahram and Monir, Hedayat accepts his negligence with embarrassment, and Ahmad confesses to his guilt.

The play is a complex network of ping-pong dialogues. The characters’ relationships turn from friendship to hostility, and vice versa, instantaneously. The game of Mafia depicts the reality of their relationships and the position of each person in this regard. Meanwhile, there are some bitter sub-narratives that parallel the story of the friends’ betrayal of Monir and Shahram: Gholamreza and Shabnam’s violent and quarrelsome marital relationship is void of mutual understanding and sympathy for one another. Mahnaz and Ahmad’s seemingly strong relationship turns out to suffer from a serious problem. They are at the point of immigration for the sake of Mahnaz’s education plans. Mahnaz is pregnant but doesn’t want to keep the baby; however, her husband has accepted the immigration plan on the condition of having the baby. At the end of the play, Monir’s voice, coming from some point in the future, informs us that Mahnaz and Ahmad have not immigrated yet and that their destiny is uncertain. This bitter uncertainty is interwoven throughout the structure of the play: in Gholamreza and Banfsheh’s relationship, which is a perfect example of love/hatred; in Arya’s love for Hedayat, which is never expressed and is always on the verge of fulfillment; in an immigration which is forever suspended; in a baby’s birth which is uncertain; in the destiny of Shahram, who is never known to be dead or living; and in the condition of Monir, which is unknown to us. The entire play takes place at the goodbye party which is held to celebrate Mahnaz and Ahmad’s immigration, the immigration which is a metaphor for all the ambiguities in the play.

The Mafia’s excellence is indebted first to meticulous and competent directing and a well-written play. Placing the Mafia game at the center, which carries the load of all the conflicts and chaos of the play’s universe, Afrooz Forouzand has created a complicated, organic structure narrating the story of unending suspension and bitter confusion of these young people, who are not committed much to the values of friendship and marriage. The other strength of the play is the lifelike and calculated dialogue, which is performed masterfully by the talented actors and actresses. In addition, choosing the right actor/actress for each role contributes to performing natural and believable roles. Also, the effective stage design and decoration should not be ignored. The space is divided into two sections: the living room and the balcony. The balcony is separated from the living room and auditorium by a large glass wall; even so, the voices of the characters in the balcony are transmitted to the audience. This way, characters can commute between the balcony and the terrace, which creates a sense of spatial variety for the audience. Reflecting the image of the spectators in the darkness, the balcony glass functions as a mirror before the play begins. The play introduces itself by holding this mirror up to the audience and inviting them to see themselves.

Note

1 “Mafia, also known as Werewolf, is a party game created by Dmitry Davidoff in 1986[2] modelling a conflict between an informed minority, the mafia, and an uninformed majority, the innocents. At the start of the game, each player is secretly assigned a role affiliated with one of these teams. The game has two alternating phases: night, during which the mafia may covertly “murder” an innocent, and day, in which surviving players debate the identities of the mafia and vote to eliminate a suspect. Play continues until all of the mafia have been eliminated or until the mafia outnumbers the innocents” <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mafia_(party_game)>.

The Mafia was staged in Baran, a nongovernmental venue in Tehran, from February 3 to March 18, 2017.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Baharak Sahami.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.