“There are bombardments constantly on the outskirts of Donetsk, while in central Donetsk they stage beauty pageants and literary parties, and the cafes work all night.” – Yehor Makiyivka, 2019

2019 marks the fifth year of the ongoing conflict in Eastern Ukraine. What began as a number of street protests against former President Yanukovych’s suspension of an EU-Ukraine agreement in 2013 soon became a fully blown war between Russian separatists the Ukrainian military: the Euromaidan protests and their bloody suppression; the sudden annexation of the Crimean peninsula; the subsequent declaration of independence of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions; the tragedy of Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17; the negotiations of several ceasefires and unsuccessful Minsk peace deals. Most of us will remember having heard about these events in recent years. But as time went by, the war, its over 10,000 civilian casualties and more than 1.5 million displaced people, have lost their newsworthiness. To break this silence means to stand up and speak for those unable to do so, trapped somewhere along the 280-miles-long frontline.

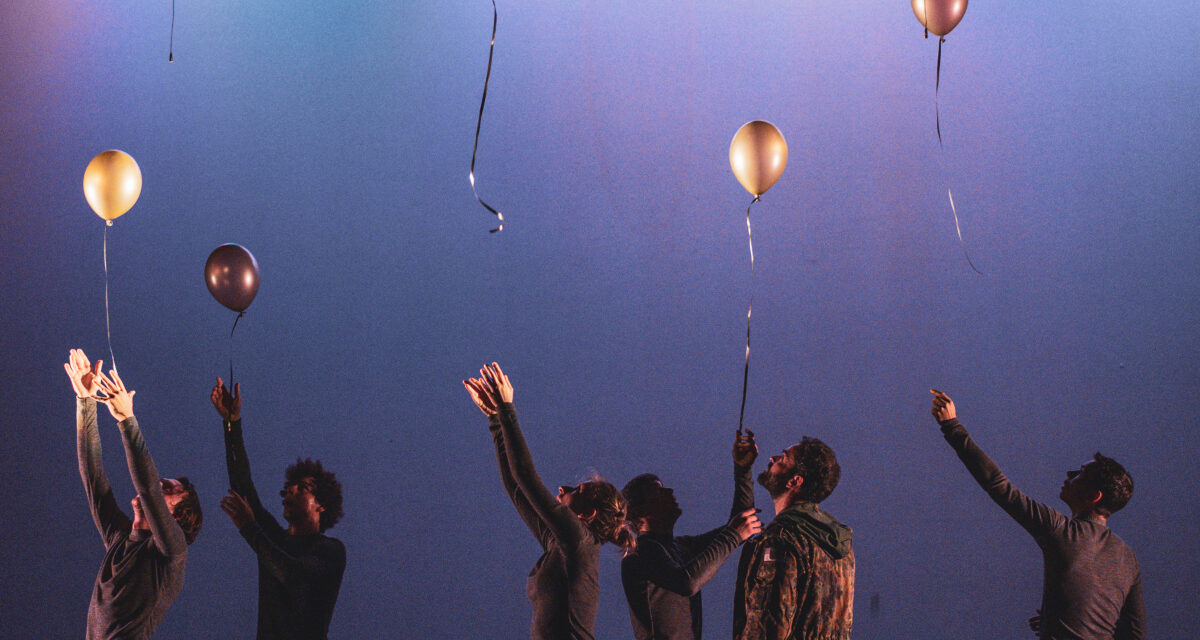

Interbeing – Stories of a Current War. Image from the reposted article.

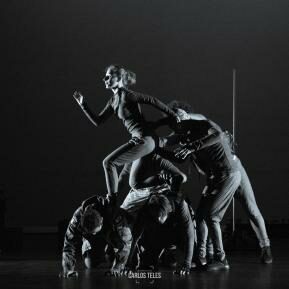

After the Vaults Festival’s showcase of Counting Sheep – Staging a Revolution earlier this year, the Cockpit Theatre hosted the world premiere of a new performance that puts the forgotten war into the spotlight. Interbeing – Stories from a Current War is an explosion of diverse performance styles from acrobatics to mime, dance and object animation. It creates a colorful canvas to the beats of an original score to express the multilayered battles that individuals fight when forced to adapt to drastic change.

The international ensemble around Ukrainian-Swedish Artistic Director Lana Biba presents a story of life, love, and loss based on the lived experience of soldiers, residents, and artists, pulled together over a period of almost two years. Archive photographs from the Donbas region serve as the visual frame. Together with real-life interviews, they build the foundation for the partly autobiographical script.

Interbeing – Stories of a Current War. Image from the reposted article.

The audience follows the story of a handful of characters and watches them transform in the whirls of conflict. We’re introduced to a young man who spends his time spraying graffiti on city walls, a cheerful primary school English teacher and a photographer, carefully scouting the city for the perfect motif. They’re three people that go about their ordinary lives. But then everything changes. Military tanks appear; people assemble in the squares; the young graffiti artist is recruited into the army. Yet, some things stay the same: the teacher still goes to work in the morning and the children still come to school – until there’s a loud noise one morning. A missile hits the school. No more children. Now, everything has truly changed.

Having left the city with a group of people, the graffiti-kid-turned-soldier, the teacher and the photographer, now working for the press, find themselves somewhere in the woods. Scenes alternate between calm evenings pf storytelling stories, sudden skirmish, fallbacks, and parties around the fire. We observe how individuals are forced to adapt to their new surroundings. In a world where death is omnipresent, the teacher swaps the crayon for a machine-gun. People who didn’t know each other before are ready to die for each other and the cause they all stand for. The photographer steps onto a mine. There’s a clear and loud clicking noise, then the shock in his face. The graffiti kid swaps places with him. All he asks for is the last photograph with his gun.

We don’t know how long the group’s been fighting, how many people they lost and how they got back home. Once back in the city, the photographer’s celebrated for his work documenting life in armed conflict. The teacher’s back in school; the two of them are a couple and live together now. Their lives appear normal, they even have a dog. But behind the facades of work and a rich social life both have to bear the trauma of war. At times, their joint experience eases their suffering, but the journey of recovery from PTSD is different for each of them. They long for each other’s embrace but are unable to fill the void within themselves. The photographer has trouble to accept that people around him continue with their lives as if nothing had happened. They socialize and tell jokes, have parties, children – and are happy. All the while, he’s eaten up by guilt. Why did he survive? The protagonists have taken the fight off the battlefield into their home, against each other and within themselves. It’s a war they can’t win.

Interbeing highlights that throughout this continuous war, everything is connected. It underlines the absurdity of war, where love/hate, sadness/happiness, disbelief/hope all co-exist. As one of the people interviewed for the show states, “we never cried so much as during the war, but we never laughed that much either.”

Interbeing – Stories of a Current War. Image from the reposted article.

Interbeing – Stories of a Current War was presented at the Assembly Rooms in Edinburgh.

This article originally appeared in Central and Eastern European London Review on August 7, 2019 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Juno Schwarz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.