Tonight, I discovered the gasp index. Or maybe just re-discovered. The what? The gasp index. It’s when you see a show that keeps making you exhale, sometimes audibly, sometimes quietly. Like a soft punch to the stomach. During this show, I gasped about five times, then I stopped counting — I was hooked. I was obviously in the right place: the Royal Court has the reputation of being a powerhouse (to use a marketing term) of new writing. Yet, often my recent experience here has been of seeing old writing in a youthful guise; but this time is different — it feels like the real thing. From the start, Mancunian playwright Miriam Battye’s Scenes with Girls grabs you in its loving grip. And then shakes you around for some 80 minutes. In the end, it spits you out. Sounds mad, but it feels great!

As the title makes clear, the piece is composed of scenes, in fact, 22 short scenes which just feature young women. It’s a flatshare drama about three 24-year-olds: Tosh and Lou live together, and they know another young woman called Fran, who used to live in the same place. In the playtext, the epigraph is from a brilliant novel, Emma Cline’s The Girls: “Poor girls. The world fattens them on the promise of love. How badly they need it, and how little most of them will ever get.” The world’s narrative is boy meets girl, they have sex, they marry, and then come the kids. The subtext, often spoken out loud, is that the girl is validated by the man: her existence is made real because of the men she knows, because of the man she goes out with.

Now Tosh and Lou have decided to contest this narrative, this ideology, this normal, or normative, situation. Instead of using men to confirm their identity they have determined to do without them. Well, sort of. As an alternative, Tosh and Lou have given up on regular lovers, but they are not the same in their behaviour. While Lou has sex with different partners, she doesn’t have a steady boyfriend; even more radically, Tosh has nothing to do with men. She says they don’t interest her. She doesn’t need them. Radical separatism 2.0. But gradually both of these ways of living begin to raise some obvious issues: how far can such choices be rational? Are they just a reaction to early life experiences? How can you rebel against normative situations in a healthy way?

As time passes, the strains in Tosh and Lou’s relationship become more intense. Neither want to have sex with women, but their emotional lives are complex and ever-shifting. Emotionally, they are a couple. Both are well educated and articulate so they discuss their feelings with, apparently, a clear consciousness. Apparently. At the same time, they are often visited by their friend Fran. Fran is different. She is less cool. Less well read. And she has met Mister Right. She can’t stop talking about him. In fact, they are going to get married. She is part of the narrative of normality, and so she is soon the victim of stinging critical comments from both Tosh and Lou.

Battye writes this story, with some lovely twists and turns, with enormous freshness and laser-sharp perceptiveness. The dialogues have a gob-smacking vitality and originality. As well as the interaction between the women, she pens some short scenes — charmingly called “Hooptedoodles” — that, true to the word’s definition, hold up the narrative, but briefly, and in a good way. The stand-out phrases come thick and fast — “throw up a kidney”; “we are not just sediment”; “human equivalent of a lasagna” — and Battye’s writing sparkles with both provocative ideas and emotional resonance. It’s great. So you can easily forgive the slightly slender quality of the entertainment.

On a personal level, there is a sharp contrast between Tosh, who is very cool and intellectual (“theoretical”), and Lou, who is more instinctive and spontaneous (“practical”). Their common ground is not only their idea of separatist politics, but also that they think that Fran is stupid. But is she really? Battye brightly satirises the Bechdel Test because Tosh and Lou and Fran talk only about men, and about sex, and their own relationships are left to peek out between the pauses in this explicit chat. And some of this is very explicit indeed. She touches on the possibility that some women can have coercive control over other women, that school girls bully each other, and suggests that all same-sex friendships are a form of love. And then what, she asks, is female pain? And is giving up sex a wise act or just frigidity?

What makes me gasp during this show is not just the explicit talk about female sexuality, but the shadow of mental disturbance that hovers around the characters. At various moment, both Tosh and Lou think that they might be suffering some kind of breakdown, that their ideas of a different way of living might be “mad”. One example is the numbness that Lou feels after she’s had sex with a random man; she describes her body as being like an arm with pins and needles. Later on, when the two friends interact with Fran we see that they, and especially Tosh, can be casually cruel, mocking the normality of the outsider’s feelings and aspirations. So much for female solidarity. Yes, this show is sketchy but there’s enough emotional truth here to make you gasp more than once.

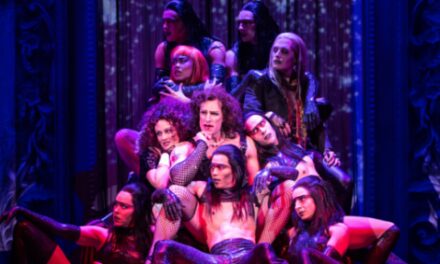

Sympathetically directed by Lucy Morrison, and neatly designed by Naomi Dawson with a coolly abstract set, Scenes with Girls is like an exciting blast of fresh air blowing through the often stale world of contemporary new writing. Its youthful appeal is enhanced by excellent performances from Sex Education’s Tanya Reynolds as Tosh, making her theatre debut, and Rebekah Murrell’s Lou, with similarly good work from Letty Thomas, whose calmer performance is a welcome contrast to the high-energy of the other two. All three are completely convincing, whether they are tentative, joyful or hit by agony. It’s very early days, but if the rest of this year’s new writing offer is half as good, I will be in heaven.

This review first appeared on The Arts Desk.

Scenes with Girls is at the Royal Court until 22 February.

This article was originally posted at Aleks Sierz on January 21st, 2020, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.