Sanhita Manch’s third edition will stage four original plays that celebrate homegrown talent in myriad ways, says Vikram Phukan.

Coming at the heels of the recently announced Hindu Playwright Award — which went to V Balakrishnan for Sordid— is yet another venture that seeks to unearth new Indian playwriting talent. This is the third edition of the Being Association’s Sanhita Manch initiative, and this year, they have extended their ambit to include not just plays in Hindi, but also in Marathi. Their final roster of four original plays has been selected from a field of more than 300 entries by an eminent panel of jurists which has included the likes of Satish Alekar, Ratna Pathak Shah and Atul Tiwari.

The Hindu Playwright Award is similarly specific in its criteria when it comes to language, considering only works in English, and the sole winner takes home a handsome cash prize of ₹2,00,000, which is also the total purse shared by, for the first time, Sanhita Manch winners, who are not ranked in any order of merit. “They are such a diverse set of plays spanning genres and sensibilities. Each of them stands on their own terms,” explains Rasika Agashe who, alongside partner Mohammed Zeeshan Ayyub, conceived of the idea of the initiative n 2016, citing the dearth of homegrown Indian plays as the trigger.

One important facet of the enterprise is that all selected plays are mounted into productions and staged as part of an opening gala of performances, which will take place this weekend. This is particularly significant, because many award-winning plays in other competitions lie unproduced and unpublished, and really, the proof of the pudding when it comes to a script for the theatre lies in its staging. “For our festival, with its focus on writing, the playwrights are all involved in the making of these first productions of their manuscripts,” explains Agashe. Additionally, the plays will also be compiled into a tome, yet another aspect of Sanhita Manch that ensures a kind of posterity often not available even to plays that are already in circulation, and have been performed umpteen times.

Also, to protect the sanctity of the writer’s vision, the volume of collected plays (for which the sole Marathi entry has been translated into Hindi), will feature the writers’ drafts submitted to the competition, and not a version that might emerge or evolve through a rigorous rehearsal process with other collaborators coming on board. “This was something we discussed a lot because plays do evolve when taken up by directors with their own take on the material,” says Agashe. This is a real-world conundrum, because even in the case of classic plays, often it is a script that has seen several productions, and accompanying alterations, that is made available to print.

But, it is (and must be) the playwright who has the last word on what might be considered her work’s definitive edition, while allowing future makers some leeway (or none at all) to interpret or faithfully represent the play, as they see fit.

The directors invited to stage the productions include the Bhopal-based Vihaan Drama Works’ Sourabh Anant, who has taken up Swapnil Jain’s Romeo Juliet in Smart Cities of Contemporary India. Jain hails from Jaipur, and his play is set in a metro, where young lovebirds Mridul and Vaibhavi find it difficult to meet, because of the gender-exclusive rental spaces they live in, even as the culture police, Bhole Bhakt Mandal, are predictably looking to bust amorous dalliances in the neighborhood. The Delhi-based Flying Fathers Art Association’s Rajesh Singh is helming Rahul Rai’s Kebab, where the eponymous meat delicacy provides a Muslim family its reversals of fortune. Apurv Sathe will direct the Marathi play Adhyat Mi, Sadhyat Tu, Madhyat Ma Kuni Nahi by Swapnil Chavhan. Produced by the Maharashtra Culture Centre, the play excavates the human propensity for cruelty.

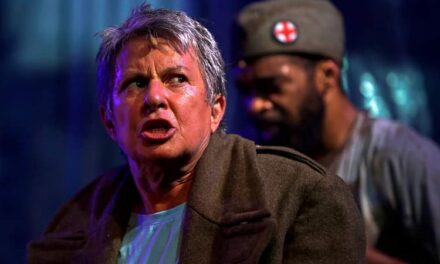

The final production is Agashe’s — Amit Sharma’s Radhey, a play on Karna that draws from Ramdhari Singh Dinkar’s timeless classic poem Rashmirathi, but strongly underlines the underpinnings of caste in the story of the great warrior from the Mahabharata.

This article was originally published by Vikram Phukan in The Hindu on August 22, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vikram Phukan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.