In an intimate performance space in New York’s East Village, a quietly consequential experiment is taking place: women of color are telling stories. On a recent night, I saw two performances that were part of the Mabou Mines SUITE/Space initiative, a program that includes mentorship, development, and access to space for rehearsal and performance. One performance was biographical, one autobiographical, both were elucidating and deeply moving.

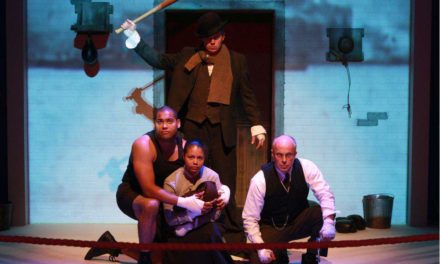

Cinthia Chen’s Anna May Wong, The Actress Who Died A Thousand Deaths, uses adept split-role casting and live cinematography to reflect on the story of the first, and, let’s face it, still one of the only, Chinese-American movie stars. Rebecca Wei Hsieh plays the younger Anna, headstrong and determined, the Anna who defies her conservative laundryman father (Matt Ting) and vamps opposite Sessue Hayakawa (Randall Trang) in Daughter Of The Dragon. As the older Anna, Elizabeth Sun shares the stage, remembering, watching, sometimes directing her former self. Experience has tempered the older Anna. Because of anti-miscegenation laws, she was prohibited from sharing onscreen kisses with male costars who were white, meaning, of course, almost all of them. But that wasn’t the only societal barrier to Wong’s sexuality. Chen’s production dramatizes her sexual relationship with Marlene Dietrich, enticingly played by Nellie Blue. (Perhaps to keep our sympathy on the right side, Wong’s alleged lover Leni Riefenstahl does not make an appearance.)

Anna May Wong and Marlene Dietrich. Photo by Tucker Mitchell.

The two versions of Wong are used to great effect when both explore ideas about liberation and self-expression. The younger Anna struggles to break free from the oppressive expectations of her family. In a tense scene presumably set in her adolescence, her father, who insists on calling her by her Chinese name, Liu Tsong, scolds Anna for skipping Chinese school to go to the cinema while criticizing the way she folds laundry. Her escape is imminent: already she has rejected the parts of her heritage and family that she deems foreign to herself. But Hollywood is not the place for her to make a clean break. Later, the older Anna strains against being typecast. The only roles available to her are exotic, dangerous Oriental beauties. (So what else is new? Fifteen years separate Crazy Rich Asians from The Joy Luck Club.)

In the most powerful scene of the show, the two Annas simultaneously discuss a yearlong trip to China, and both struggle to smooth out dialectical differences in two different languages. The older Anna tries to cleanse her Mandarin of the Taishan accent, while the younger Anna, a native Los Angelean after all, tries to sound more “proper,” that is, British. They repeat the same phrases, each in a different tongue until their diction exercise has turned to tearful shouting. This isn’t just an issue of self-expression, but the question of who is the self, doing the expressing?

Anna May Wong and Marlene Dietrich. Photo by Tucker Mitchell.

The integration of live cinema theater is one of the most organic uses of film technology I’ve ever seen on stage. Throughout the play, camera operators and a boom operator move around the actors, and their footage appears on an upstage screen. It makes sense concretely of course because Anna was a movie star. The device allows the actors to recreate iconic scenes from Anna’s movies, and once, to project real footage from a Paramount picture. But it also makes visible the central tensions the play explores: the many-sidedness of a complex person, a bold and ambitious American woman of color, who cannot be reduced to a single freeze-frame. There were always two camera operators on stage, but only one had her footage projected onto the screen. I found myself wondering what would have been visible from the other perspective, and realized the limitations of a camera’s fixed vantage point.

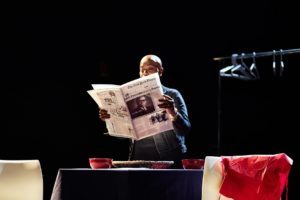

Another kind of many-sidedness is on display in Marcelle Davies-Lashley’s Liberian Girl In Brooklyn, the play paired with Anna May Wong. In this one-woman-show, Davies Lashley plays about ten different characters. They’re her family members and figures from her neighborhood, the people who helped her become the many-sided woman taking the stage. Her powers of transformation are mighty. In the beginning of the show, she plays her own grandmother, a woman who left the United States do missionary work in Liberia. (Davies-Lashley weaves a Liberian history lesson into the play, which was helpful for me because prior to this performance, the only Liberian girl I knew was a Michael Jackson song.) She plays her own mother, Gertrude, tenderly recreating her sing-songy Liberian accent and depicting her lovable eccentricities. Davies-Lashley was one of seven children, and she tells us her mother never called her by her name; she was “little girl.” The night I saw the show, I realized I was sharing the audience with some of Davies-Lashley’s friends and relatives. They were identifiable by how they chuckled and nodded in recognition as if seeing Gertrude there on the stage. As for me, all I could do was admire Davies-Lashley’s eye for the kind of details–vocal patterns, carriage, coded expressions of fear and hope–that makes a person at once an individual, and part of a community.

Liberian Girl In Brooklyn. Photo by Tucker Mitchell.

The play is punctuated by original songs, each in a different style, and Davies-Lashley is as communicative a singer as she is a story-teller. Dancing, she makes her body large and then small, now bouncing, now undulating, as the song demands. Seeing her use this range of expressive modes–narration, song, and dance–I was reminded of two currents of oral literature. The first is the West African tradition of the griot, a bard who is equal parts poet and historian. Davies-Lashley uses her considerable gifts to tell the story of her own family as both a band of singular individuals and emblems of their time. With the idealistic mission to Liberia in the mid-twentieth century, and the importance of this cultural legacy when they returned to the United States, Davies-Lashley’s was one of many families who participated in this round-trip exodus. It’s part of African, American and African-American history, yet it’s perhaps best explained through art.

The second oral literature tradition is homegrown–it’s hip hop. I don’t mean to suggest that Davies-Lashley incorporates literal hip hop elements into her play, any more than she explicitly evokes a Malian griot. None of the songs she sings even veer in that direction; as a singer she’s soulful and melody-driven. But both traditions are there in the background, Liberia on the one hand, Brooklyn on the other. Hip hop, specifically rap, represents a rebirth of pure poetry and oral story-telling unprecedented in American literature. New technologies and virtuosic musicians enhance but cannot substitute for the central figure: a wordsmith telling her own story. The celebratory, self-loving ethos of hip hop, especially from the 1970s of Davies-Lashley’s childhood, is part of the spirit that puts a little bounce in Brooklyn’s ounce. Hometown pride comes from knowing who you are, who your community is, and where you belong. It’s a feeling, incidentally, that Anna May Wong may never have known. But no self-respecting Brooklynite is without it, and it’s at the heart of one of the most important American artistic traditions of the twentieth century.

Something special happens when you bring these two plays together, as SUITE/Space has done. Chen and Davies-Lashley took the opportunity to breathe new life into these stories, to let these voices ring out. What would Anna May Wong, a Hong Konger girl in Los Angeles, have to say to Marcelle, a Liberian girl in Brooklyn? What would happen if they met as grown women, who had both traveled, experienced, and accomplished so much? Decades divided them, so did cultural traditions, societal expectations, and family norms. But I bet they would have found some common ground, for example, on the power of story-telling to both explore and transcend our own perspectives.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Abigail Weil.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.