What does it really mean to do political theatre? Does the theatre even hold any potential to trigger political change, especially in an increasingly fascistic state? And what better group to ask these questions than a troupe of actors and directors coming to terms with their role in a society haunted by rising far-right extremism?

Samuel Gallet’s Mephisto [A Rhapsody] seizes such an opportunity to have the theatre hold up the mirror to its very own self. Adapted from the German author Klaus Mann’s 1936 novel Mephisto, Gallet’s play transposes the original plot from the early twentieth century to the present-day France, where the small provincial town of Balbek turns into a hotbed of fascist turmoil and artistic self-interrogation. Kirsty Housley’s confidently witty production at the Gate Theatre, which uses Chris Campbell’s slick English translation, grapples with the play’s radical energies in a highly self-aware and resonant key.

On the whole, Mephisto [A Rhapsody] is about the members of the “Balbek theatre family,” as they variously come into contact with—and discuss—the provocations of the extreme-right Front Line party. Should they keep staging Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, or instead program the antifascist Ernst Toller’s plays? How are they to deal with the pig heads left in front of their building? Does it even matter what they do on the stage, night after night, while people shout out racist slogans outside? Throughout, we get the chance to meet and understand several characters of differing persuasions, but at their center is an actor named Aymeric (played by Leo Bill with fascinating manic energy), whose pursuit of fame and delusions of grandeur ultimately lead him to strike a Faustian bargain with the government.

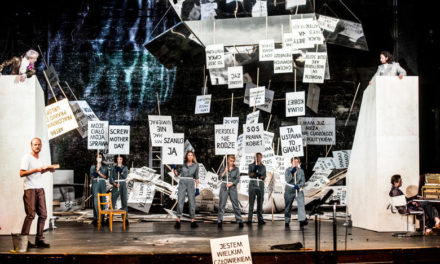

For a play with intricate storylines and rapid changes in setting, Housley’s staging works surprisingly well: on a particularly narrow stretch of a stage, almost like a one-sided runway, her actors sit on chairs or stand side by side, sliding into and out of their scenes with casual ease. Behind them is a reflective surface that invites the audience to recognize themselves as an integral, if distorted, part of the world of the play. Costume racks and technical equipment are visible on the sides, and the actors wait for their scenes sitting next to the audience. This is all too fitting for a play whose metatheatrical layers are juicily bountiful. The effect is even more apposite in those moments when Anna-Maria Nabirye, as the only Black member of the cast, addresses the audience directly with acerbic, reflexive comments on the racial politics of both this work and the theatre industry at large.

While the first act holds itself together in dynamic but consistent ways, the second act—despite intriguing developments in the plot—proves not to be as focused and tight. A few scenes assigned to the peripheries of the stage, coupled with another few that could have been pruned (or even cut altogether), detract slightly from the punches that this second half delivers with otherwise well-earned force. The contributions of Jessica Hung Han Yun’s lighting are simply indispensable here: her neon-heavy, rapid-fire and increasingly phantasmagoric design injects into the production a darkly zany atmosphere—one that encapsulates the extremes reached by the society in question.

So do the accomplished performances of the cast: Leo Bill’s jumpy, raucous, and at times cold-blooded Aymeric is nicely counterbalanced by Rebecca Humphries’ subdued portrayal of his lover Barbara. Anna-Maria Nabirye is electrifying as the famed actress Juliette Demba, and Tamzin Griffin does great, nuanced justice to both of her artistic-director characters. Though the character of Michael—a staunch supporter of the Front Line, and a horrific white supremacist in his own right—feels often too flat (and certainly bloated with all the evil attributed to him), Rhys Rusbatch brings a fine control, and some insight, to his unflinching darkness.

Among the most commendable aspects of this irresistibly engaging work is its sustained and provocative commentary on many of our contemporary discourses—about far-right politics, the autonomy of the arts, and the responsibilities of the artist to the society (if any). In this respect, Mephisto [A Rhapsody] is a very timely and topical play, but one that does not embarrass itself while being so. (By no means an easy task, this latter.) And the Gate production’s stripped-down, transparent take on what could have fallen prey to a more contrived interpretation adds to the evening a most welcome layer of instantaneity.

After all, if the theatre does not ask these questions of itself, who will?

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Mert Dilek.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.

![Samuel Gallet’s “Mephisto [A Rhapsody]” at the Gate Theatre](https://thetheatretimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/image-1-1280x640.jpg)