London’s Royal Court theatre, which proudly boast of being “a leading force in world theatre for energetically cultivating writers,” is currently exploring our culture of fear, our psychological response to the long shadow of the War on Terror, and the ramifications of our contemporary age of anxiety and austerity. And, as Cordelia Lynn’s play, One For Sorrow, which is playing in its small Theatre Upstairs, shows, the venue has chosen an aesthetic that is not traditional naturalism, but a more symbolic and metaphorical approach. Now, on the main stage, Rory Mullarkey’s Pity offers a surreal state-of-the-world account of our society, and of its discombobulations.

The story begins with a pre-show, that lasts about 30 minutes, in which the audience enter the theatre from the back of the stage, cross its artificial grass lawn and steps, and—along the way—get offers of ice cream to lick, tombola tickets to enter a draw, and other aspects of a village fête. Members of the Fulham Brass Band play some tunes. All this is not really necessary, but I suppose it’s meant to put you in a playful mood, to prepare you for the games to come. And, when the play starts, they come soon enough. At first, however, everything is normal. A person—who we later discover is called Alex—wakes up on an ordinary day, in an ordinary small town, in England. He’s not working so he decides to hang out in the town square.

He does so. He is “watching the world go by.” Nothing much happens. It’s a nice day, so people are out and about, buying ice creams, walking their dogs, and smiling. It begins to rain. Then a history professor appears, with his daughter, a young woman who works in a department store, and whose name—we later discover—is Sam. They get ice creams. Then things start going weird. The professor is struck by lightning and dies. Totally random. Alex and Sam immediately get married, have sex, and start a family. A bomb explodes. Another bomb explodes. Bombs are going off all over the place. Basically, the whole world goes mad: wars break out, armies commit atrocities, pandemics ravage the population.

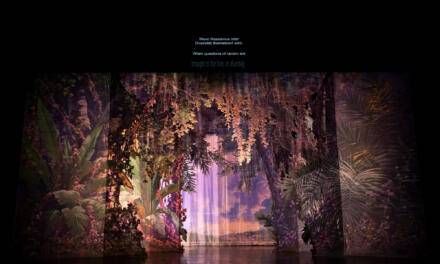

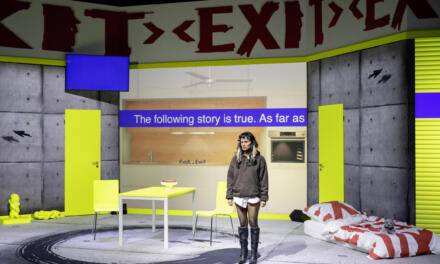

All this is performed like a crazy cartoon, with bright costumes, bright sets, and bright dialogue. Everything is shiny. Everything is fun. Everything is surreal. It’s all more Monty Python than Edward Bond. A British female Prime Minister dithers and is unable to make up her mind about what kind of sandwich to eat; she sings a song about it. How can this person lead the country? How can this person negotiate Brexit? No worries: she is soon assassinated. The killer has a ridiculously silly rifle. He claims that he was acting alone. Ouch! Refugees cross the country. Tanks appear on stage. Near the end, as an ecological disaster strikes, an ocean liner passes by.

Alex and Sam survive much of this madness, at each crisis repeatedly reassuring each other that “I’m alright.” Note that, for all their affection, they never ask: “Are you alright?” This is a picture of a very solipsistic generation. Yet they do stick together, and they do help each other. Human contact is possible even amid the worst disasters, amid the most terrible wars and most terrible natural disasters. It’s a brightly optimistic thought in a stage world that rapidly becomes totally unpredictable and wild. An absurdist universe where reality and meaning come under uncontrollable stresses: yes, it’s the culture of fear alright.

Amid the comic day-glo action, Mullarkey—whose The Wolf From The Door was staged at this venue in 2014—explores the theme of Englishness. The play begins in an immediately recognizable world of village fêtes and local mayors, and ordinary folk doing ordinary English things. But there some more implicitly troubling questions: Are we such a selfish, unthinking nation that we can tolerate our way into disaster? Or do we really believe, in our complacency and egoism, that horrible things simply can’t happen to us? Is bad stuff something that only happens to other countries, to other kinds of people, to other ethnicities? To break out of such complacency maybe we need to start imagining a world where things also go wrong for us. This is the political splinter in the wound that this play opens up. And it’s a cut that is festering.

If this sounds very serious, I have to say that much of the comedy in Pity is really quite silly, quite surreal, quite strange. And, because this is a Royal Court play, there are several satirical references to other, really serious, plays in the canon. One cannibalistic sequence is a joke on Sarah Kane’s Blasted; the absurdist escalation is a nod to Caryl Churchill’s Far Away. One celestial visitation is a dig at Tony Kushner’s Angels in America. Each death is accompanied by Chopin’s Death March; Beethoven’s Fifth ramps up the excitement. Tragedy goes hand-in-hand with farce. Mullarkey’s sensibility is pretty nihilistic. Everything could, he suggests, collapse at any moment, and how would we cope if civilization fell apart?

Sam Prichard’s production embraces the play’s anarchic worldview with enormous energy, and with the aid of Chloe Lamford’s colorful set, makes sense of the senselessness of an apocalyptic spasm. Abraham Popoola and Sophia Di Martino play Alex and Sam with an appealing openness, and there is an evident joy in all the cast’s performances. To name but a handful, Sandy Grierson, Helena Lymbery and the wonderfully comic, in this case, and physically nimble Francesca Mills keep the laughs coming in this epic of surrealism. But, as the title and the final song alert us, there is an obvious question: does the play inspire pity in a pitiless world? Answer: No, I don’t think it does.

Pity is at the Royal Court until August 11.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.