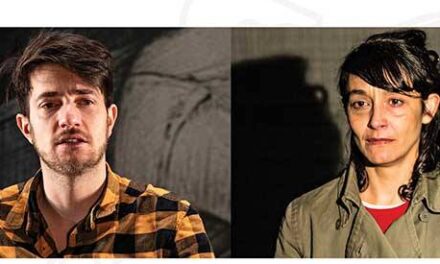

Future is Feminine introduces American audiences to innovative Romanian women artists remixing Ibsen with two shows running in repertory: Me. A Dollhouse and Ibsen Incorporated. Take a look at the world through their eyes, 25 years after the fall of communism. The event is presented by Romanian Cultural Institute, Bucharest Odeon Theater, Bucharest Comedy Theater, Romanian Association for Performing Arts, Ibsen Scholarships, and Drama League New York. A rare example of devised theater on the Romanian stage, Ibsen Incorporated is, to quote director Catinca Drăgănescu, “a way to investigate the influence of the capitalist society on the fundamental inter-humane relationships and the way these relationships are reconfigurated today.” In this show satire becomes a great weapon for social critique.

Me. A Dollhouse – Nora Remix depicts a lonely woman on the stage who recalls her life. The sensorial world in which she lives is born out of vibrant, dynamic video projections, that tell a fascinating story. A soprano sings what she cannot say. The very personal performance in which Carmen Lidia Vidu is emotionally mixing Ibsen, noir film and live music is inspired by Nora from A Doll’s House by Henrik Ibsen and has a hypnotic, aggressive and poetic ambience.

For reasons generated by the historical context, Romanian and East-European cultures have not followed the rhetoric of the first or the second waves of feminism, but they are now in the position to directly engage with the post-feminist debate. With very little interest in topics like domestic violence, sexism in the media, equal pay, childcare system, and representation of women in public life, these patriarchal societies are very well served by the idea that feminist topics are now obsolete as young girls have all the opportunities in the world. The affirmation of “girl power” is already taking over and replacing the much needed feminist debate. We have arrived at the point where feminist ideas are lost, as Elaine Aston observed in reference to contemporary women’s playwriting: “Fatigued by the idea of second-wave feminism, a third-wave generation of women were ‘sold’ on the post-feminist promise of a personal freedom and empowerment.”

We have synchronized ourselves with Western societies’ approach to “girl power” as promoted through the media, without going through all the struggles of raising consciousness about women’s issues which could benefit the community. If in the Western societies, feminist politics are in danger of being forgotten, we have not even got to the point of understanding the necessity of fighting to make these policies happen.

Issues which had been central to the formation of the women’s movement are rarely to be found in the Eastern European popular culture. They are already replaced by the myth of the self-made woman, the super-woman able to take care of her family while being a career woman too, never to complain and always multitasking. Instead of discussing these serious issues, women’s magazines in Romania are all promoting this Superwoman stereotype, as a recent study observes. The very idea of a women’s movement is already compromised, and these topics find a place only in the academia which is very isolated from the public discourse.

Following the same pattern, Romanian theater has never addressed the idea of feminism as a socially transformative politics and – as women playwrights are still a rarity – theater is not “engaging in critiques of girl power as a substitute for feminism” either.

The few exceptions confirm the rule: young theater director Catinca Drăgănescu included in-depth arguments in the argument of her feminist theater production Ibsen Incorporated included in Hedda’s Sisters project:

“The patriarchal hierarchy is mostly the same. The pressure put on a woman today asks of her to excel in each and every one of the assigned social roles. She needs to prove herself as a worthy competitor in the professional area, but she also needs to be a sex symbol and a wife and a mother. This multiplication of the social roles is a direct result of the equal rights struggle and it often confronts women with the difficult choice of either to renounce or to fake one of these roles, so that they can rise to the society’s ideal expectations. Being competitive on all levels – from the practical to the symbolic one – is the main reason for a move toward an androgyny of women who, from an evolutionist perspective, becomes her survival tactics in a masculine referential system. This change has a profound impact on the feminine collective mentality, even if it has not become visible socially or physically. It stays undercover, hidden like a secret, like a disease or a malformation.”

This worrying gap between feminist politics and the girl power discourse, this “conflict without a conflict,” was the starting point of Hedda’s Sisters project focused on Ibsen’s feminine characters, aiming to use them as a tool to showcase contemporary women’s perspective and empower Romanian women artists in the theater. The project started within the framework of the first edition of The Bucharest International Theater Platform with the theme The Future is Feminine – a four days all-women festival taking place in Bucharest, Romania.

Hedda’s Sisters project involved twelve actresses and performers of all ages and three women directors with a total of 25 persons working for the project. 90% of the team was feminine. Drăgănescu is one of the three young women artists whom I selected to direct productions in the frame of the project Hedda’s Sisters. Empowering Women Artists from Romania and Eastern Europe, with the aim to use Ibsen’s play for an artistic display of the “female gaze.” The other two directors are Carmen Lidia Vidu, who staged Me. A Doll’s House, inspired by Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, and Ioana Păun, who staged The Enemy of the People. All three productions had all-women casts.

Why Ibsen for a feminist theater project?

As a theater critic for more than 15 years, I have realized only late in my career that all the classical plays based on a female character I was watching on the Romanian stages were reproducing the masculine point of view. It was more than obvious in Ibsen’s plays because they showcase powerful female characters. In the frame of the local festivals, almost all the invited international productions of Ibsen’s plays were directed by male directors. Amazing actresses were embodying ideas that were not theirs at all, following the same mechanism that almost all women follow in the society they live in, guided by mass-media and cultural stereotypes. The rule seems to be that one has to bend to the majority if one wants to fit in. In this equation, Ibsen plays a very strong part because his plays are the “pillars” of the classical theater repertory. His work offers a lot of reasons for contemporary creators to revisit it and use it to address contemporary issues on stage.

In August 2010 I participated in the Ibsen Festival organized by The National Theater in Oslo, and all the Ibsen productions I saw were directed by men. It was then when I first asked myself “What if female directors would have the chance to direct Ibsen’s plays?” Four years later I applied for an Ibsen Scholarships award with a project based on this idea. I won the grant in the following year, and three new productions directed by female artists were included in the repertory of three Bucharest public theaters.

It turned out that Ibsen can be an inspiring choice both for those female artists who believe that theater should be a sociological laboratory, but also for those who are more focused on developing their own aesthetic vocabulary. Different results can come out of the same laboratory, depending on who has developed the study, what they were searching for, and what they attempted to discover. A change of perspective is sometimes all we need to stimulate creativity. Six years later, two of these productions will be presented in New York at HERE Arts Center 15 to 20 of November, in the frame of a tour titled Future is Feminine- New Voices in Romanian Theater, presented by Romanian Cultural Institute.

It is important to note that the most significant contribution to the performative turn in Romanian theater is made by women artists, who are more open to experimentation. One of the most important aspects of the Hedda’s Sisters project is the performative approach used by the three female directors. This was both a joy and pain for the actresses involved in the project, given the traditional training of Romanian actors and their lack of familiarity with performance theory or practice.

In the final evaluation report of the Hedda’s Sisters project, the actresses are underlying this aspect of their experience. Some of the actresses found the new type of work process very difficult, unlike the usual one implying a text already written and a very clear cast of characters. Devised theater is a very rare enterprise on Romanian stages, and even the most open-minded actors have a difficult time taking part in it. Dana Voicu, the most experienced of the performers in Ibsen Incorporated, confessed it was difficult for her not to have the full text from the beginning of rehearsals:

“It was very hard for me to work under pressure with an ever changing structure of the show. We have arrived at the final structure after a difficult process, and there was a lot of insecurity until the day of the opening. The most pleasant moments were those when all the actresses and the director were talking about their personal experiences so that we could find the most significant moments to dramatize them and insert them into the show.”

As it turns out, the pleasure of contributing to the final structure of the show was sometimes overshadowed by the stress of starting off without a structure, as in the traditional theater. Experience, in this case, had the effect of rather curbing enthusiasm. On the other hand, for Ioana Flora, who played the title role in The Enemy of the People, being part of this project meant “a challenge to take part in a production mixing Stanislavskian theater with performative theater which I started to like very much.”

Another aim of the Hedda’s Sisters project was to encourage Romanian actresses to show their creativity in the absence of a director. The first step of the project was the national audition for which the actresses were invited to submit a short demo in which they presented a monologue from one of Ibsen’s plays. Over eighty actresses of all ages submitted demos, most of the monologues being prepared and directed by themselves. Thirty of them were selected by the directors to take part in the live audition, and twelve ended up in the cast of the three productions. The performative quality of Hedda’s Sisters productions is not only given by the actresses’ contributions to the text and the collaborative working process, but also by the aesthetic choices the female directors made for the productions. All three directors worked closely with choreographers, and two of the productions include live music, while one of them also has a powerful multimedia component. The result is a decisive step towards the performative turn in all three productions. The use of new media practices seduce new types of audiences, from the visual arts and contemporary dance fans, to film and punk concerts goers (for Me. A Doll’s House) or civic activists (for Ibsen Incorporated).

Ibsen Incorporated and Me. A Dollhouse will be presented at HERE Arts Center 15 to 20 November 2016.

All details and tickets here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Cristina Modreanu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.