Edmonton, Alberta. Connor Meeker reviews Tetsuro Shigematsu’s Empire of the Son at Edmonton’s Citadel Theatre:

Having originated at Vancouver Asian Canadian Theatre in 2015, Tetsuro Shigematsu’s autobiographical solo show continues its Canadian tour to the Citadel Theatre in Edmonton. Performed and written by Shigematsu, Empire Of The Son is an intimate portrait of a son trying to connect with a father that he feels he barely knows.

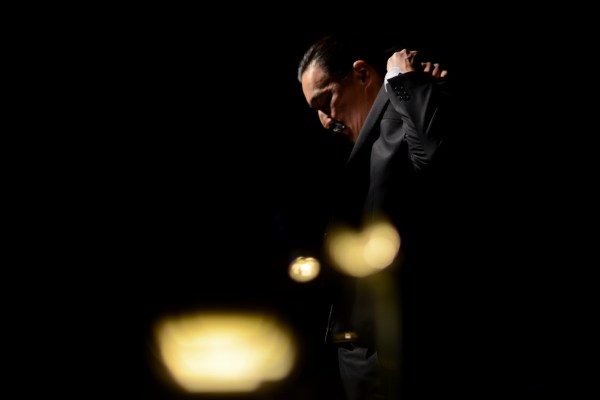

Tetsuro Shigemetsu in Empire Of The Son. Photo by Raymond Shum.

Empire Of The Son explores Shigematsu’s fraught relationship with his father, Akira Shigematsu, who died just before the show’s original premiere. It’s a familiar story of cultural distance and misunderstanding between first- and second-generation immigrant parents and children. But what makes the production interesting is Shigematsu’s unique approach to the story. He recounts his emotionally distant relationship with his father in a fragmented, memory-like way, jumping between anecdotes from the childhoods and adult lives of both him and his father. In less capable hands, Shigematsu’s text could simply become a string of meandering stories—but the charm and candor of his performance are what hold the pieces together.

Shigematsu weaves artifacts from his father and the rest of his family through his stories, using interview footage and family photographs to conjure their presence. We learn that Akira Shigematsu emigrated with his family from Japan to Great Britain where Tetsuro was born, and then to Canada. As his father ages, Tetsuro realizes that he barely knows him, prompting Tetsuro to record interviews with his father about his life. Despite the historically significant events he had lived through, Akira is a stoic, reserved man, who is reluctant to talk about himself.

Tetsuro Shigemetsu in Empire Of The Son. Photo by Raymond Shum.

When his son presses him for details about the time he had tea with the Queen, for instance, he can only muster that he was “not the only one there.” More jarringly, he downplays the sickness he felt after Hiroshima as a simple bout of food poisoning. Discomfited by the magnitude of his father’s restraint, Tetsuro longs to bridge the divide between them. Although they are father and son, culturally and personally they are worlds apart.

The dramatic premise of the production springs from Shigematsu’s realization that he hasn’t cried since he was a child, which he realizes through a conversation with his two young children. Shigematsu tells us that he wants to be able to shed authentic tears at his father’s upcoming funeral—in preparation, he hopes that the presence of an audience while talking about his father will help him practice.

In a clever combination of low and high-tech theatre magic (set design by Pam Johnson) Shigematsu manipulates an on-stage camera to project close-up images of various miniatures. In one scene, he uses his fingers to represent his father and his teenage-self having an argument about skateboarding. In another, he creates a haunting representation of the bombing of Hiroshima. This device allows Shigematsu to generate poignant images to work with his poetic text and adds visual interest to his otherwise understated staging.

Tetsuro Shigemetsu in Empire Of The Son. Photo by Raymond Shum.

In Shigematsu’s responses and reactions to his memories, there is a constant elusive tension underlying his relationship with his father—Shigematsu wants to be able to tell his father that he loves him, to be able to comfortably climb into his father’s hospital bed like his sisters do—but this impulse is never quite satisfied. The masculine expectation to maintain an emotional reticence in familial relationships is magnified by the expectations of his Japanese-Canadian culture. Though he tries to reach out to his father, a gulf always remains between them. Referring to his interviews with his father, Shigematsu remarks that his “questions were the Rockies,” and his father’s answers were “long prairies of silence.”

Empire Of The Son’s bracingly simple theatricality, paired with Shigematsu’s honest performance, give the production its emotional power—a deeply personal examination of a father and son relationship across cultures, generations, and lifetimes.

This article originally appeared in Alt Theatre on May 15, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Connor Meeker.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.